This article is a preview from the Summer 2017 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

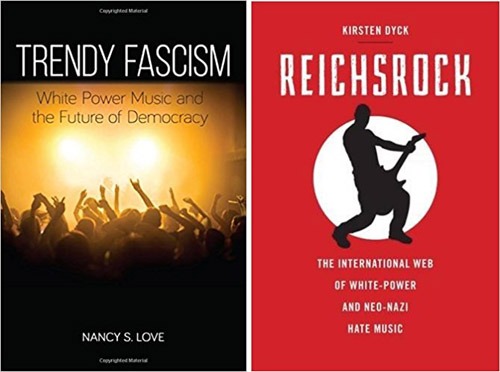

Reichsrock (Rutgers University Press) by Kirsten Dyck

Trendy Fascism (State University of New York Press) by Nancy S Love

Towards the end of last year, in the wake of the Trump victory, some odd stories appeared in the press about an emerging musical genre called “Fashwave”. Although it has never been clear whether it actually existed or was just a form of trolling, Fashwave appeared to be 1980s synthesiser music co-opted as the in-house sound of the alt-right.

Whether or not Fashwave is a thing, its emergence as a talking point illuminated the fact that the recent rise of far-right populism in the US and UK hasn’t really had a soundtrack. This is surprising as there is a long tradition of far-right British and American popular music: bands such as Skrewdriver, Bound for Glory, Rahowa and many more. Yet it doesn’t seem to have been an important factor in today’s resurgence of far-right politics.

This is partly ideological, partly aesthetic. The alt-right communicates via sly allusions and trolling, a contrast to the blunt directness of white power rock. Most of the prime movers behind Trump in the US, Ukip in the UK, and their fellow travellers do not see themselves as neo-Nazis or even necessarily as racists. Stephen Bannon or Nigel Farage would not be comfortable at a skinhead show.

Yet hate rock, white power music – the names vary, although there is an underlying coherence tying it together as a cluster of genres – remains very much alive. It is even expanding in scope and support in some places. So it is vital to try and understand not only what it is and what it represents, but also how it fits into the populist ascendancy. Two scholarly studies published in 2016 (but too early to take into account the political earthquakes of the second half of the year) help to illuminate this milieu, but ultimately leave as many questions as answers.

Nancy Love, an expert on cultural politics, in her exquisitely badly titled Trendy Fascism, offers a US-centric perspective on white power music. She covers the basics, which will be known to anyone with some familiarity with this area: the pivotal importance of Ian Stuart Donaldson’s band Skrewdriver in developing white power music in the UK and inspiring similar bands worldwide, George Burdi’s Rahowa in the US and the growth and subsequent splintering of Resistance Records, the bizarre pubescent girl-duo Prussian Blue.

What Love is most interested in is trying to account for the appeal of this kind of material. She has not conducted field research or interviews with white power fans and musicians, but draws on accounts by those who have left and repudiated these scenes. Love combines a fairly clunky appreciation of the power of aggressive music to inspire and excite with an equally clunky class analysis of the participants of white power scenes:

Participating in the white power music scene allows dispossessed white teenagers to perform their precarity and resistance to it. Former white supremacists frequently relate how white power music got them involved and how they then used the music to recruit others.

This begs the question: why resist this way? Why this rather than the plurality of other options for surviving in a neo-liberal America? Love, while recognising the white power scene as a separate space that is unlike “mainstream’” music scenes, also emphasises the continuities:

A continuum exists between hegemonic liberalism and white supremacy, and the nationalist, racist, sexist, and homophobic messages found in popular music illustrate it. The white power music scene is the extreme that illuminates the white supremacist norm in liberal democratic politics; liberal democratic principles, including what Herbert Marcuse calls “repressive tolerance,” help to sustain the political spaces where white supremacists can mobilise support.

This approach is somewhat crass and overlooks significant discontinuities, but it isn’t entirely wrong. Perhaps Love might answer the riddle of the lack of a soundtrack for the Trump/alt-right triumph thus: there didn’t need to be, there was always enough cultural material for white supremacy to draw on without “resorting” to explicit white power music.

Still, it would be a mistake to see white power music as a self-imposed ghetto, a kind of optional add-on to a wider white supremacy for those too angry or too unsubtle to disguise it (or to play with it, alt-right style.) In fact, white power music may be more significant than it might seem if one confines one’s analysis to the US or UK. Another recent – and much better – study of white power music scenes, Kirsten Dyck’s Reichsrock, demonstrates that, in some respects, the UK and US white power scenes are no longer the centre of gravity within the global scene.

While the UK scene led the way in the 1970s/1980s and the US in the 1990s, they have subsequently faded due to internal disputes, defections and (at least in the UK) persistent anti-fascist harassment. The white power scene is now heavily globalised, facilitated by the internet, but with hot spots in certain countries and regions. Despite government and police crackdowns, Germany still produces hundreds of bands and recordings and there are significant scenes in places as unlikely as Japan and Columbia. The real heart of the action is now Russia and parts of Eastern Europe, home to some of the most aggressive activists and productive bands, in a political environment that is at times conducive to far-right movements.

As Dyck shows, the globalisation of white power music scenes has been accompanied by a change in the very nature of far-right politics. Xenophobic nationalism co-exists with, and in some cases has superseded, a globalised white identity. Whereas true Nazis would never see a Slav or a mestizo Columbian as truly white, the boundaries of whiteness appear to be being stretched. Although this development has not gone uncontested, the contemporary malleability and dynamism of white power ideology are worrying developments inasmuch as they might enable activists to burst out of what were previously insular and distrustful nationalist enclaves.

Dyck also emphasises that white power music is increasingly as dynamic and innovative as its ideology. While Oi!-style skinhead stomps remain popular, white power music now includes varieties of what is known as National Socialist Black Metal, neo-folk, industrial and even (I promise you I did not make this up) hip-hop and dub. You are unlikely to enjoy Skrewdriver unless you have some ideological sympathies with them, but some of the newer forms of white power music are more interesting and alluring (I speak as someone who very reluctantly enjoys some neo-folk and NSBM acts).

It may be that the older styles of white power music and their attendant scenes in the UK and US are fairly moribund. It may also be the case that, so far at least, the resurgent far-right in the US and UK may not be as musically propelled as their predecessors were. But we need to look globally with concern at the newer forms of white power musical activism. The soundtrack for the white revolution is here, even if many of those who might embrace it haven’t heard it yet.