This article is a preview from the Autumn 2017 edition of New Humanist.

On 28 February 1972 at 5.50am, Frank Aycliffe recorded an important decision. “I think my uncertainty of whether to go to the hairdressers’ has been solved,” he wrote. “I have decided not to, but wait and see what things are like in another month’s time.”

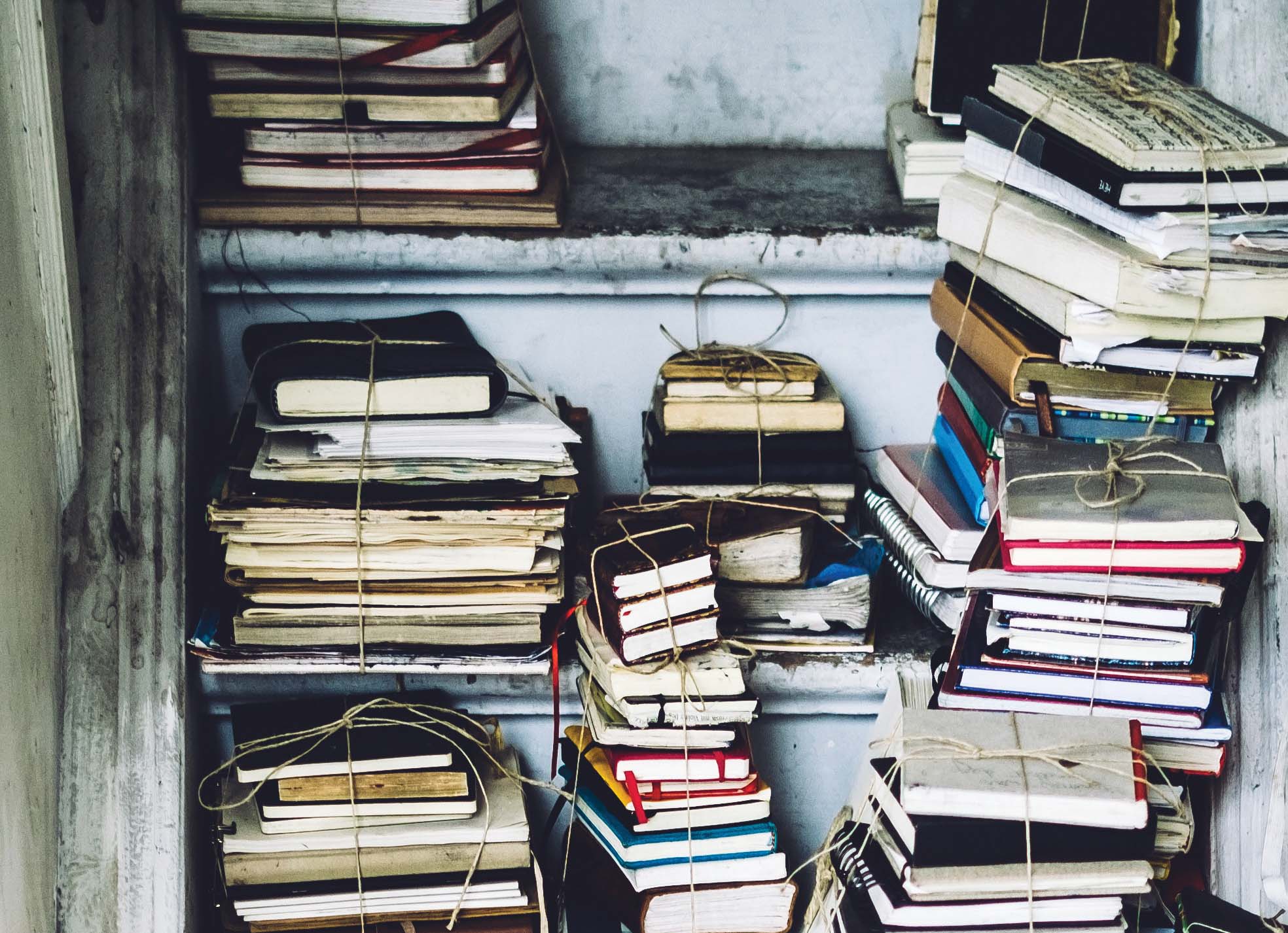

Aycliffe put his deliberations in his diary. It was later transcribed by his daughter and, after his death, donated to the Great Diary Project, set up in 2007 to “provide a permanent home for unwanted diaries of any kind”. He wasn’t a famous or notable person, but this record of his life’s small, seemingly inconsequential details is now preserved at the Bishopsgate Institute in east London, alongside at least 7,500 other diaries and journals. They can be consulted by the public at any time, and a selection has recently been on display at Somerset House as part of an exhibition titled Dear Diary: A Celebration of Diaries and their Digital Descendants.

The impulse to create a personal narrative and record it can be traced back centuries – it is inextricably linked with how we think about life and existence. Marcus Aurelius, the second-century philosopher, is often credited as the author of the first example of what we would now call a diary. This work, today referred to as Meditations, originally had the Greek title Ta eis heauton, which translates roughly as “to himself”. It comprises personal notes on philosophical ideas, particularly in relation to Stoicism (a key tenet of which is self-knowledge). On the page, he plots thoughts about how to live a better life through maxims such as “put an end once and for all to this discussion of what a good man should be, and be one”.

There are several reasons why we keep diaries, which sometimes conflict and overlap. It’s an insurance policy against the failure of memory, an answer to the question “what if, five years from now, I can’t remember what I did today?” It can be a form of self-mythologising, providing a version of a life that can be disseminated into the world. The division of diarists into those writing with posterity in mind and those creating a solely private text is not clear-cut; it is rare to come across a diary with no intended readers at all. Perhaps most significantly, the very act of writing can be cathartic. Setting down experiences can provide clarity and absolution even if the writer has no intention of turning back the page to read what came before.

This last effect has been the focus of renewed attention in the last couple of decades. In 1992, in her book The Artist’s Way, the writer Julia Cameron explained a technique that she called “morning pages”, which advises sitting down first thing each morning to handwrite three pages of whatever comes to mind. Cameron sees this regular practice as part of a search for something intangible. “As we move towards our dreams, we move towards our divinity,” she wrote. The idea is to “catch yourself before your ego’s defences are in place” and – like Marcus Aurelius’s own attempts – capture something essential of yourself on the page. More recently, the habit has become trendy among creative Silicon Valley types, always on the lookout for life’s latest hack.

The blank page hasn’t always been so enticing for diarists. Those first few pages that many pre-prepared diaries contain – the conversion tables for weights and measures, the astrological data – are the vestige of a once-popular document: the almanac. Before the ready availability of other reference works, almanacs were vital to the functioning of daily life. By the 16th century, they outsold the Bible. With blank pages interspersed among the tables, they are the forerunners of today’s desk diaries, establishing the calendar as the framework for personal observations and normalising the juxtaposition of general data with everyday life. The Dear Diary exhibition contains plenty of evidence of how this trend developed and was tailored to particular uses. On show is everything from diaries for housewives, such as the Boots Home Diary, which included domestic information, to the Pony Club diary via the Collins Farmers’ Diary and the Druids’ Journal (this last had a particular emphasis on phases of the moon).

Seeing dozens of diaries carefully laid out in glass cases for an exhibition prompts a fundamental question, however. Why do we preserve some and not others? Are some moments and individuals more worth keeping than others? The mission of the Great Diary Project is to collect any and all diaries that are available, regardless of who wrote them and where they come from. Prior to that, the same lines of prejudice and coincidence that influence all aspects of history were in operation.

The diaries of men of status, such as the naval administrator Samuel Pepys, the writer John Evelyn or the scientist Robert Hooke, were far more likely to receive the initial protection and publication that would ensure their survival down the centuries. It wasn’t until 2011, for instance, that the diaries of the 19th-century Yorkshire industrialist Anne Lister were given UNESCO protected status in recognition of the invaluable contribution her record of life as a lesbian in the north of England at that time has made to historical understanding. Context is everything – it’s very difficult to know now what will be of consequence or interest to scholars in years to come.

Like Pepys, Lister wrote partially in code, to protect more controversial or private observations. The need for secrecy and the fear of discovery have long dogged diarists – a display in the exhibition of the padlocked diaries marketed at young girls confirms that. But since the advent of the digital diary, in the form of a blog, vlog or social media account, a trend in the opposite direction has emerged. The idea of “oversharing” online is denigrated, but as the inclusion of footage from “mummy vloggers” in the Dear Diary exhibition makes explicit, the kind of contemporaneous record of their life that a YouTuber is keeping is arguably no less valid than Pepys’ enumeration of all the actresses he lusted after.

More and more, the idea of a diary floats free of the printed page. Can a person’s search-engine history not function as a kind of personal journal, revealing their thoughts and activity at each moment? Or the output of a personal fitness tracker, which captures all of the wearer’s activity, including how fast their heart was beating? The association between keeping a diary and the impulse towards self-improvement is ancient.

Yet this idea of the “quantified self” still has a place on the page. Thanks to the spread via social media of new diary trends like “bullet” or “dot” journalling – which its creators describe as “an analog system for the digital age” – the idea of keeping a notebook as a record is still going strong. A combination of a mediaeval commonplace book, a to-do list, a calendar and a traditional diary, a bullet journal is an intensely personal document. Bullet journallers give careful thought to aesthetics, often posting pictures of elaborately designed “spreads” on Instagram. Rachel Wilkinson Miller, author of Dot Journaling: A Practical Guide, devotes dozens of pages to handwriting practices, and advises sketching designs in pencil first to keep the notebook pristine.

Yet the content is still a slowly building picture of a life, told through the minutiae that make up a self. In 2017, the font might be different to when Frank Aycliffe was weighing up whether to get a haircut in 1972, but the goal is the same. Writing a diary, Miller says, “gives us a complete picture of who we are.”