This article is a preview from the Winter 2017 edition of New Humanist.

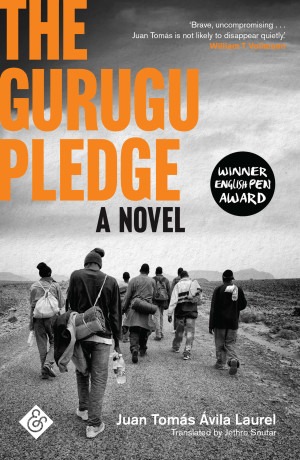

The Gurugu Pledge by Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel (translated by Jethro Soutar)

Few media reports seem to consider the reality for many African men, women and children prepared to risk life and limb in order to reach Europe. It is a subject ripe for rigorous examination. As the main narrator in Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel’s extraordinary novel observes, exaggeratedly: “The story of a continent emptying itself in order to go to another one has to be told.”

It’s a gargantuan task but Ávila Laurel rises to the challenge. Based on true accounts, and deftly translated by Jethro Soutar, The Gurugu Pledge follows the fortunes of a group of African migrants gathered on the slopes of Mount Gurugu in sight of the Spanish city of Melilla. They live in caves, ironically referred to as “the residence”, and play football to keep warm and stave off boredom as they wait for the right moment to scale the barbed-wire fence that divides Morocco from Europe. The men address each other as “brother” and bond through the countries and languages that they have in common.

Ávila Laurel creates a vivid sense of their shared humanity as they struggle to survive, “living like lepers”, while dreaming of the opportunities that surely await them in Europe. During the day, a small group descends the mountain to beg for food. At night, story-telling helps preserve their sanity and offers some light relief. The men take it in turns to relate their personal histories and their various reasons for leaving their native countries. Voices overlap as they interrupt one another and finish each other’s sentences. The narrator delays the telling of his own misfortune: “I always acted as though I had no story to tell, as though I had nothing to say. The fact of the matter was that if I’d started to talk, if I’d started to tell of the things I’d seen and the tales I’d heard, I’d never have stopped.”

Ávila Laurel gets to the heart of what it means to leave one’s homeland, in particular the yearning to retain one’s dignity. The Gurugu migrants are marginalised and at times openly hated. Many on the mountain have been treated as sub-human while on their journey to a better life, and this, in turn, leads them to behave inhumanely. Hunger forces a group of Cameroonians to kill a macaque monkey to eat. The Moroccan police are outraged by this perceived barbarity but lessen the punishment to a beating after considering Sura 2, Verse 65 of the Koran: “Be ye apes, repugnant and hated ... any beast implied to be repugnant by the Koran simply could not be defended.” Later, the narrator is horrified by a journalist’s account of a group of Africans whose bodies had washed up on the Spanish coast: “You could see it quite clearly from the video footage: they’d been killed. Either that or they’d all suddenly died while swimming to the beach, which was as hard to believe as the official version, that they’d drowned at high sea.”

Born in Equatorial Guinea, Ávila Laurel writes from bitter experience – his outspoken criticism of President Obiang’s dictatorship led to his exile in 2011. Many on the mountain are fleeing corrupt regimes but the camp is a fertile breeding ground for tyranny. Abhorrent characters like Omar Salanga, whose notoriety precedes him via word of mouth, and the shady Aliko Dangote, are quick to exploit the power they hold over others. The pair are responsible for the brutal mistreatment of two women, a minority in the group, and the veterans on the mountain are called upon to dispense justice. Instead, there is a collective decision to alleviate tensions in the camp by a mass storming of the fence. As the narrator observes sadly, when it comes to crossing the border, it is every man for himself.

We’re living in increasingly volatile times. The media continues to fuel anti-immigrant rhetoric, the far right is gaining ground, and compassion fatigue has set in. As Ávila Laurel aptly illustrates, fiction can offer alternative narratives and encourage empathy. There will always be people fleeing conflict, persecution or poverty. The Gurugu Pledge serves as a searing indictment of hatred of “the other” and an urgent call for tolerance. The final message is clear: Europe needs to build bridges, not walls.