This article is a preview from the Winter 2018 edition of New Humanist

I keep my conversations with young people to a minimum. Not because I lack interest in what they have to say but because I can no longer hear any one of them talk for more than a few minutes about their future life without being overcome by guilt.

Only a month ago I had to escape to the bathroom after learning from a bright young woman that unless her work contract was renewed, she would have to give up her rented flat and look for work outside London. If I’d stayed in the room, a moment would have arrived when I’d have felt compelled to admit my personal responsibility. I’d have had no option but to issue a fulsome apology for the Iraq war, the gig economy, global warming, austerity and Brexit.

Sometimes, though, I miss my cue. Only recently at my partner’s 70th birthday party, one of the guests, the 22-year-old grandson of an old university friend, started talking about the problems of still living in the family home.

“You can’t take a woman back to your place when your place is so clearly still your father’s place,” he said.

I might have made my usual escape at this point if Matt’s face had not suddenly brightened.

“But there is one thing,” he said. “I may not have a place of my own but I have found the woman of my dreams.”

“How do you know?” I asked.

“It’s all down to progress. The Internet. In the last five years I’ve been out with over 50 young women, all selected for me by a nice middle-class dating site. Every one of them more or less met my online criteria. They were left-wing, agnostic, fond of indie bands and Stewart Lee. Before dating sites I’d have been lucky to have met any one of them. But as it was I could choose the very best. Lisa. The woman of my dreams.”

“Isn’t that a bit mechanical?” I said. “One series of Internet ticks gets together with another series of Internet ticks? No room there for the different or the unexpected.”

Matt was unmoved. “How much choice did you have at my age? The girl next door or that friend of your sister’s or the blonde from the youth club. Hardly a galaxy of talent. More a gene pond than a gene pool.”

I joined in the laughter but later that night I found I was busily compiling an inventory of my teenage choices. My first love, Bernadette O’Leary, had indeed been close friends with my sister, Madeleine. And it was also uncomfortably true that I’d only discovered the appeal of my second love, Pamela Wilson, when we’d ended up facing each in a Paul Jones dance at the Brownmoor Youth Club.

But Bernadette and Pamela were wonderfully different, nowhere near to meeting any exacting criteria I might now lay down on the Internet. Bernadette was a devout Roman Catholic who regarded French kissing as a mortal sin, thought Hilaire Belloc was a major poet, and had a framed picture of Frank Ifield on her bedside table.

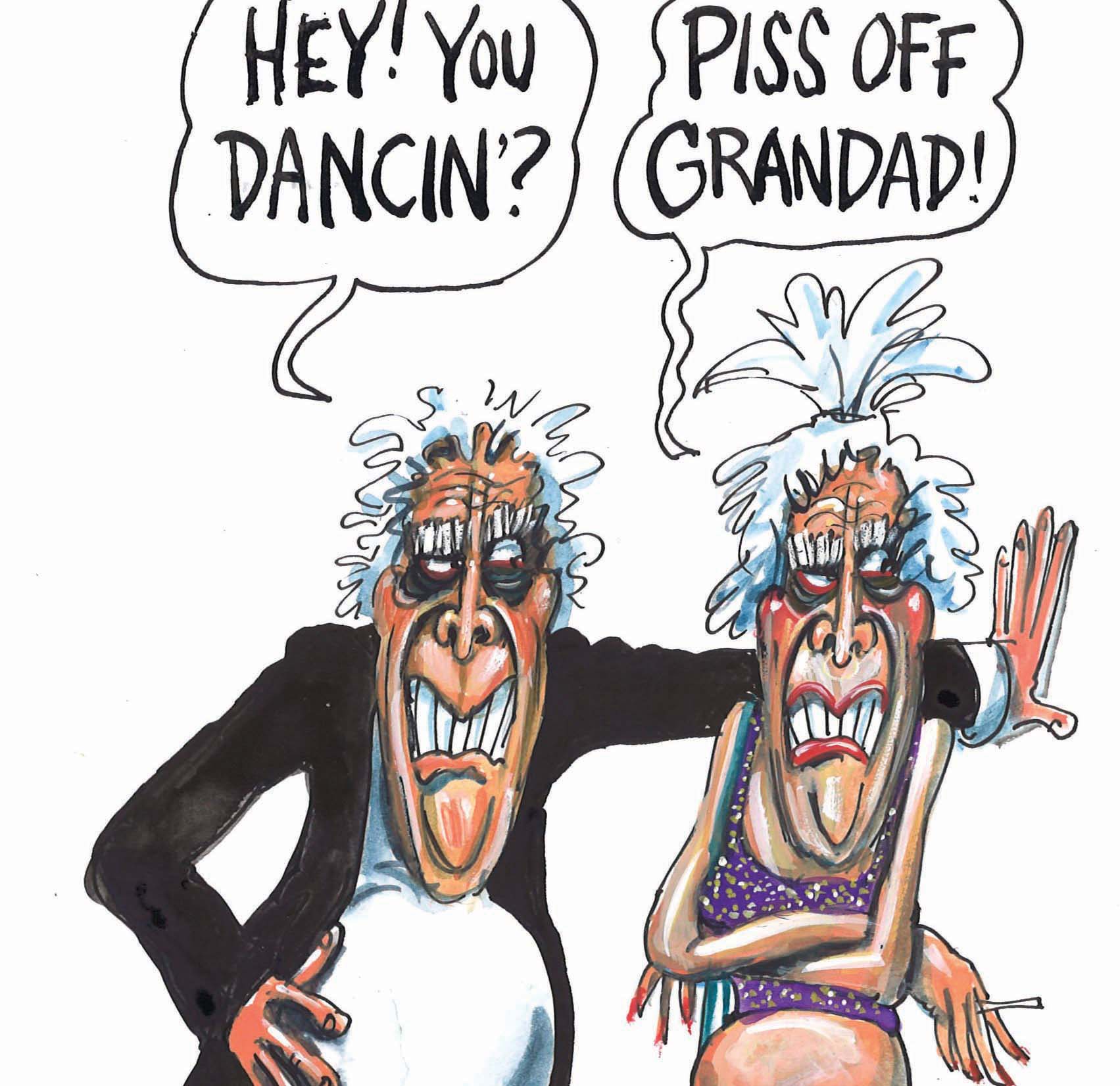

And what about the four years of my young life I’d lavished on Pamela? Her only pleasure in life was dancing the quickstep every Saturday night to the rhythms of Bill Gregson and his Broadcasting Orchestra in the Tower Ballroom, New Brighton. As I all too clearly remembered, my sole reason for putting up with so many evenings shuffling miserably around that sweaty dance floor was the thought that one day soon, on the sofa in her living room after her mother had gone to bed, she might at last let me put my hand up her top.

I couldn’t evade the truth. I’d spent years and years of my youth not so much pursuing difference as desperately trying to ignore it while I sought to assuage my adolescent lust. And it had been hell.

Perhaps Matt was right. Extreme similarity was the new romantic ideal. In this sad modern world we could only find true happiness by being with someone exactly like ourselves. Was it too late to try? I spent my last waking moments mentally composing a hypothetical entry for a dating site.

“Elderly but still active ex-academic who supports Liverpool through thick and thin, revels in the music of Miles Davis and John Coltrane, relishes the writing of Howard Jacobson and Julian Barnes, delights in the humour of Cheers and Seinfeld and Frasier, seeks similar.” But I couldn’t stop the adolescent in me from adding: “big breasts an asset.”