This article is a preview from the Spring 2019 edition of New Humanist

Wearing the Trousers: Fashion, Freedom and the Rise of the Modern Woman (Amberley) by Don Chapman

If you really want to be deadlier than the male, then try wearing his clothes. And this spring ushers in a new take on the trouser suit. You can choose from bright citrus colours or more sombre tuxedo styles, slouchy palazzo pants to culottes, cordurouy to satin. Trouser suits, writes the Times fashion editor Anna Murphy, “can be a way of having your cake and eating it; of looking pulled together, professional and ready to win in what is (still) a man’s world, while also signalling your femininity, your point of difference, and the fact that said man’s world is already teetering, and that it is only a matter of time before we women – in our retooled trouser suits – topple it once and for all.” Her view would certainly not have surprised the fashion pioneers of the Victorian age who campaigned to liberate women from their sartorial prison. Their story is told by Don Chapman in Wearing the Trousers: Fashion, Freedom and the Rise of the Modern Woman. From the start, he argues, women advocating the discarding of skirts were also arguing for something more far-reaching: gender equality.

It was in 1850s New York that a few women were first spotted in trousers – inspired, apparently, by hearing from travellers to the Ottoman Empire of the pantaloon styles and short robes worn by Turkish women. People like the social reformer Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and women’s rights campaigner Elizabeth Cady Stanton were early adopters. But it was when Amelia Bloomer, editor of The Lily, announced to her readers that she had taken to wearing the Turkish-style costume, that the craze for Bloomer and Bloomerism got its name and went global.

“We care not for the frowns of over fastidious gentlemen;” wrote a woman correspondent in the Times, “we have those of better taste and less questionable morals to sustain us. If men think they would be comfortable in long, heavy skirts, let them put them on; we have no objection.”

It wasn’t long before the new fashion was introduced to Britain. Another early adopter was Elizabeth Dexter, who distributed handbills to London milliners and dressmakers inviting “mothers, wives and daughters to embrace dress reform” and “join the Association of Bloomers”. Dexter went on to give increasingly packed public lectures, despite ridicule from some quarters and censoriousness from others. One of Dexter’s most persuasive arguments was, simply, for healthy living. And her warnings about the terrible effects on the body of tight stays and heavy crinolines began to be taken seriously by the medical profession.

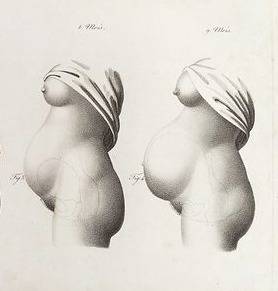

An article in the Royal Cornwall Gazette described stiff and tight-laced stays as “a diabolical contrivance for disfiguring the form and destroying health and life . . . The vital organs are displaced and their functions impaired.” Chapman gives examples of young women dropping dead from their tight lacing. One surgeon, on examining the corpse of a young woman, found that her heart and liver had been enlarged by her tight stays; another died from the bursting of a blood vessel in the lungs. Another, from curvature of the spine. Other medical practitioners noted that many women were growing fat because their unwieldy dress made exercise impossible.

Despite the warnings, many women continued to wear huge, heavy skirts and to encase themselves in tight lacing in pursuit of the perfect figure. But change was coming. During the second half of the century more women began to engage in active pursuits like overseas travel, mountaineering, archery, shooting, walking – all of which required more comfortable clothes. Perhaps the most significant development of all was the advent of the bicycle. As more women took up cycling there was a growing demand for more suitable attire: trousers. At the forefront was Lady Florence Harberton. Like Amelia Bloomer before her, she had the good fortune to be married to a feminist. Lord Harberton’s Observation on Women’s Suffrage, published by the National Society for Women’s Suffrage, argued strongly for equality between men and women. Organising meetings in her own drawing room, and campaigning vigorously for the legal and economic rights of women, Lady Harberton held an open debate on dress reform. It was priced so reasonably that working women could afford to attend. From that first meeting emerged the Rational Dress Society.

The secretary was another stalwart feminist, Mrs E. M. King, who wrote passionate denunciations of old-fashioned clothing which harmed women’s health. One of her great triumphs was the staging of an exhibition of rational clothing, featuring designs from Europe, America and many local manufacturers. But, as is the fate of so many organisations beset by the narcissism of small differences, King and Harberton fell out over a disagreement about skirts. Harberton favoured wider divided skirts like a “Syrian” design she praised; King deplored even the term “skirt” and advocated shorter, narrower trouser-like garments. So King resigned and set up the rival Rational Dress Association. Whatever the differences, new designs, patterns and catalogues proliferated.

But the most decisive transformation came with the First World War, when women began to take on the traditional jobs of men – and their working costumes. In 1916, writes Chapman, “the Secretary of State for War, Lloyd George, and the Home Secretary Herbert Samuel, stood at a window in Whitehall and watched as a seemingly endless procession of women war workers organised by the WSPU (Women’s Social and Political Union) marched past.” It must have been quite a shock to see the army of women in their overalls and trousers, some in khaki uniforms, some in farm labourers’ garb. Nothing could have better symbolised the connection between the demand for rational clothing and the demand for the vote.

After the war, when suffrage was granted to some women, there was no turning back. The age of flappers and bright young things put an end to the unhealthy and restrictive fashions of the Victorian age. By the end of the Second World War, when women had again taken on even more active roles in peacetime jobs and in the armed forces, wearing trousers had become a fact of life. But not for everyone. Right through the rest of the century and beyond, restrictions persisted in some areas on what women were allowed to wear. It wasn’t until 1968 that the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University ruled that women students could wear slacks or jeans. A decade later, the National Union of Teachers won the right for their members to wear trousers. As late as 1999 the mother of a 14-year-old schoolgirl had to take her case to the Equal Opportunities Commission to win a similar ruling. It wasn’t until 2016, after a two-year dispute, that British Airways finally agreed to allow its female cabin crews to wear trousers.

Chapman’s densely researched account ends on a somewhat despairing note, as he details the recent taboos now being placed on what women should wear – especially in countries where women in trousers had been commonplace for centuries. In 2009, Lubna al-Hussein, a Muslim journalist working for the United Nations Mission in Sudan, was arrested for wearing slacks in a Khartoum restaurant, an offence punishable with up to 40 lashes.

After widespread protest she was spared. In Syria, all primary schoolgirls have to wear a veil, even if all the teachers and pupils are female. “So much for Lady Harberton’s campaign for equality of the sexes,” writes Chapman, “so much for the Syrian skirt.”