A British environmentalist has announced plans to create thousands of carats of diamonds “made entirely from the sky”. Dale Vince, the founder of green energy supplier Ecotricity, has set up a “sky mining facility” in Gloucestershire to grow the “world’s first zero-impact diamonds”. Synthetic diamonds are increasingly popular, with a recent poll finding that 70 per cent of millennials in the US would consider a lab-grown engagement ring.

Diamonds are a symbol of true love due in part to their chemical and physical properties. While not unbreakable, they are extremely strong, formed deep within the Earth’s mantle and made of the most concentrated form of pure carbon to be found in the natural world. Hollywood helped sell their allure, most famously through the 1953 Marilyn Monroe movie Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend.

But in recent years, the mining industry’s reputation for plundering developing nations and funding bloody conflicts has increased the appeal of lab-grown alternatives. Indistinguishable from the “real thing”, synthetic diamonds are produced through chemical vapour deposition or high-pressure, high-temperature processes, both of which start with a “seed” – a fat slither of an already existing diamond. They are touted as being clean and green – producers claim they are less carbon-intensive, although the rival traditional industry has disputed this.

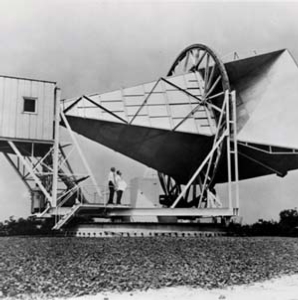

That means that definitively zero-carbon diamonds are likely to cause a stir. The Sky Diamonds facility in Stroud uses wind, solar electricity and collected rain water to produce the diamonds from carbon dioxide captured directly from the atmosphere. Vince has even said that his diamonds are in fact carbon negative. However, the process still uses carbon vapour deposition and we have yet to see whether his goal to produce 1,000 eco-friendly diamonds a month can be met. Also, there has not yet been any indication of how much they’ll cost.

This piece is a preview from the Witness section of New Humanist winter 2020. Subscribe today.