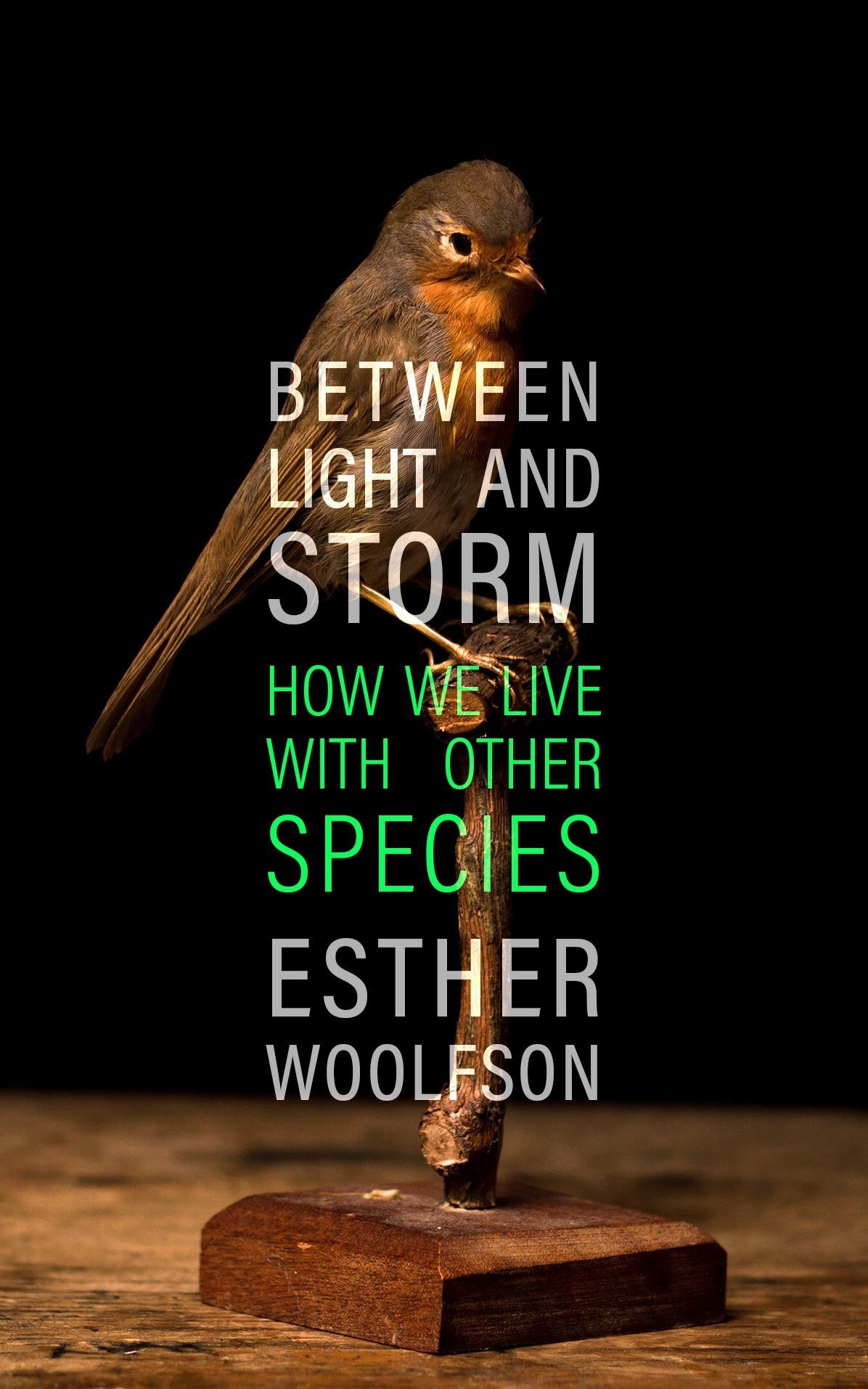

Between Light and Storm: How We Live With Other Species (Granta) By Esther Woolfson

When I was learning to fly, I watched passing birds from my cockpit with fascination. We were each a danger to the other; my propellor, their missile-like bodies. But they also prompted jealousy and admiration, their acrobatics out of my realm as a pilot and a human, no matter how many flying hours I logged. Innovation may have taken us into the skies, but we are no closer to becoming birds.

Birds are Esther Woolfson’s literary and personal speciality. She has lived with them and written books about them. They feature heavily in Between Light and Storm, which uses them, along with an impossibly large number of other beasts, to exemplify how human society lives with, among and over the animal kingdom.

It’s nothing new to suggest that humanity’s idea of exceptionalism has placed us on a separate trajectory to animals. Nor is it new to note that this trajectory has largely been bad for other living species. Woolfson asks, instead: how do we reconcile the suffering of others with benefits to our own lives and health? Inevitably, emotions slip in, and the question begins to feel less philosophical, and more pointed: how can we live with ourselves?

All the big dilemmas are here – meat-eating, hunting, experimentation, farming, fur farming. There are few aspects of society not tarnished in some way by these trades, and even the most insulated and urban among us will find ourselves unwittingly involved in an animal’s misfortune. Woolfson shows what is happening around the world, and the horrors we have bestowed upon species we’ve deemed inferior to us. This is a rabbit-hole of guilt.

As clear and shocking as the facts may be, they are weakened by recurring double-standards and biases. While taxidermy is derided as a “display of conquest and possession”, Woolfson owns a stuffed tarantula, a fact smoothed over because it was inherited “in the processes of time”. Pet owners, too, are scolded for forcing explanations of their pets’ behaviour onto them (“‘She likes it!’ when possibly she doesn’t, or ‘He doesn’t mind’ when clearly he does”). Only a page later, however, she describes a photograph of her partner’s grandfather, whose dog “lies with an air of perfect happiness on the knee of her owner”, and later describes her own pet parrot dancing with “cool brilliance” to the Moody Blues.

Christianity gets the once-over as a stand-in for the western world, which “has accepted God’s lack of compassion for the animal kingdom”. Other religions fare better. Her deference to Judaism and Jewish practices can read like a very particular acquittal (her own family, a “stolid, middle-class Scottish Jewish community”, which “would never have participated in or condoned torture”, are another exemption within an exception).

Woolfson’s research into the subject wasn’t total (no hunting trips or abattoir visits here), but her query that “if hunting is in our nature, why do increasingly few people do it?” sticks out as poorly conceived. A simple consideration of technology, city living and a general removal from the land could suffice, but there is no thought spared for the communities that rely on hunting. One wonders if her description of hunting – the “pursuit by those who value themselves too highly of those they value too little” – applies to the Polynesian fishermen, Inuit harpoonmen and New Guinean tribesmen who live beyond the benefit of 24-hour supermarkets.

But these are important moral quandaries, ones that we would all do better to contemplate. In light of Covid-19 and our raised collective awareness of wet markets, the illegal animal trade and cross-species contamination, Woolfson will no doubt find people receptive to her ideas. To those on the fence, it might prove too much hypocritical finger-wagging. “Me good, you bad” rarely wins over hearts and minds.

This book is not a comfortable read. But that is as it should be. What this book does is to force us to evaluate our own habits, our own lives, our own complicity in the suffering of others. It does this very well.

This article is from the New Humanist summer 2021 edition. Subscribe today.