Why can’t a woman be more like a man?” asks Professor Higgins in My Fair Lady, the 1956 musical based on George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. Shaw’s play had made a more nuanced point, about a young woman having motives beyond merely bagging her man, but the musical’s lyrics, half a century later, poked fun all the same:

Why do they do everything their mothers do?

Why don’t they grow up, well, like their father instead?

Historically, the lives of women writers have been paradigmatic of the outlier’s double-bind: that the exception, however successful, can be used to prove the rule. The ways in which such pioneers did what the men around them traditionally got to do were by definition public and so, therefore, was the opprobrium they risked. Despite this, by the early 19th century in Europe at least, women were beginning to “grow up like” their literary “fathers”. Yet, two centuries on, the vicissitudes that their posthumous reputations continue to undergo crystallise the continuing problem that is cultural revisionism.

A living writer establishes, by her sheer presence, the need to acknowledge her existence. She meets up with literary friends, she critiques her peers’ work, her work appears at its moment of publication. But after her death, the work alone must bear the burden of whatever prejudices its author triggers in the current cultural gatekeepers. And books cannot answer back. It is not, in fact, the case that a text “speaks for itself”. Yet, ironically, belief that it does is precisely what encourages writers to emerge from constituencies the literary mainstream ignores or disparages.

A canonical poet, overlooked

Young Elizabeth Barrett, for example, living a provincial country-house life in the early 19th century, was determined to develop into the world-famous writer of substantial pioneering literary and socio-political influence that she indeed became. Even as a child she understood the anomaly, as she later reflected:

No woman was ever before such a poet as she wd be. As Homer was among men so wd she be among women...she wd be the feminine of Homer. Many persons wd be obliged to say that she was a little taller than Homer if anything. When she grew up she wd wear men’s clothes, & live in a Greek island, the sea melting into turquoises all around it.

Still, she was determined to “grow up like her father”, her first literary mentor, who celebrated and published her juvenilia, and let her read round his library. It was her mother, however, who took time out from having 12 babies to guide her reading, introducing her to “Mrs Wollstonecraft’s system” at 13. As she wrote in an unpublished later piece, turning discreetly to the third person:

Poor Beth had one great misfortune. She was born a woman. Now she despised nearly all the women in the world except Madame de Stael – She could not abide their littlenesses called delicacies, their pretty headaches, & soft mincing voices . . . One word Beth hated with her soul . . . & the word was “feminine”.

By the time the future Elizabeth Barrett Browning was in her early 30s, she was widely read and reviewed; by her mid-40s, internationally renowned. She’d been nominated as Britain’s first woman poet laureate (though it would take another 159 years for one to actually be appointed) and become a campaigning writer who changed British awareness of social issues including child labour, rape, American abolitionism and the Italian struggle for reunification. Among the writers she influenced were Emily Dickinson, John Ruskin, Thomas Carlyle, Christina and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Rudyard Kipling, Oscar Wilde, Virginia Woolf and the North American school of the 1840s from which Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne emerged. In short, she was a canonical figure.

Yet at 40, Barrett Browning had also married a younger and less established poet, Robert Browning, who would later develop his wife’s revolutionary poetic techniques, and whose reputation in the Anglosphere has been allowed to eclipse hers. Some 70 years after her death, her achievement would be largely wiped away from popular consciousness by another Broadway hit, Rudolf Besier’s The Barretts of Wimpole Street. This hugely successful 1931 melodrama, and the three film and seven TV remakes which followed, together established the caricature of the swooning lady poetess. By 1973, The Oxford Anthology of English Literature’s critic-editors (all male) could opine:

Miss Barrett . . . eloped with the best poet of the age. Her long poem Aurora Leigh (1856) was much admired, even by Ruskin, but is very bad. Quite bad too are the famous Sonnets from the Portuguese . . . Mrs Browning’s enthusiasms . . . gave her husband much grief.

The editorial team excluded her work from their anthology, along with that of Jane Austen, George Eliot, Mary Shelley and Virginia Woolf, and all the Brontë novels. In total, less than 0.5 per cent of the volume was devoted to writing by women. (The same vanishingly small percentage, I notice, that in beer counts as alcohol-free.)

Such anthologies are staples of curricula on both sides of the Atlantic, and the intellectual fashions of the 70s have had a strong influence on today’s academics and teachers. “English Lit” is a core school subject across the Anglosphere; it’s from the ranks of English graduates that a large proportion of culture-makers – and the book-buying public – are traditionally drawn. So this wasn’t some academic spat, but a clearing-out of women from the literary canon.

"Women's writing" and Virago Press

At 13, Barrett Browning wrote in the introduction to her precocious first book, The Battle of Marathon:

Happily it is not now, as it was in the days of POPE. . . Now, even the female may drive her Pegasus through the realms of Parnassus, without being . . . traduced by her enemies as a pedant; without being abused in the Review, or criticised in society.

Perhaps she spoke too soon. Still, in the 70s and 80s, intellectual culture was shifting in more than one direction. As women’s writing became a specialism, Barrett Browning’s life and work were rediscovered, to an extent. The last full-length biography, until my own, was Margaret Forster’s in 1988. Academic studies appeared from feminist literary critics like Angela Leighton, Marjorie Stone and Germaine Greer, yet Barrett Browning’s position remained anomalous. Virago Press was founded in 1973 and transformed the mainstream experience of reading in Britain by publishing new books by women and reprinting canonical women’s writing. Yet Barrett Browning was not included in the “Modern Classics”.

In her lifetime she had, like Charles Dickens, both responded to and helped develop a widening Victorian readership. Dickens’ readers famously flocked to buy his serialised stories; Barrett Browning’s 1856 masterpiece Aurora Leigh similarly sold out multiple editions. This was the first account of a woman developing into adult personhood ever to be published in the west. It was far ahead of its time in condemning forced prostitution as rape, and advocating loving single parenthood. It was also written in the modern informal and narrative style its author, along with Alfred Tennyson and later Robert Browning, was pioneering. But it was a novel in verse; unfashionable in the second half of the 20th century, as it is today.

Poetry’s slide away from cultural centrality left Aurora Leigh and its author on the sidelines as women’s fiction was rediscovered; rather as Mary Shelley is regarded as a one-hit wonder because today’s tastes slide past the Walter Scott-like novels which followed Frankenstein. Yet the success of films like Ken Russell’s Gothic (a horror film about the Shelleys’ visit to Byron in Geneva), or 2009’s Bright Star (about John Keats) reveals 19th-century male poets do remain canonical figures in the culture, even if they are not actually widely read. Also like Mary Shelley, Barrett Browning’s good or bad luck was to marry one of these: in doing so she lost some of the traction of her own identity.

Shedding old assumptions

Scholars and biographers, while glossing over the practical literary assistance both women gave to their spouses – as copyist, editor, source of contacts – used to assume creative intervention by their menfolk. Today Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein notebooks, digitised by the British Library, demonstrate her authorship; while the timeline of authorship and publication prove it was Barrett Browning who initiated the style she and her husband came to share. Still, old assumptions remain in circulation. To correct them is not to deny that Robert Browning is a poet who displays brilliant nuance and almost visionary emotional apprehension. The point is that so is Barrett Browning: as readers discover if they can access her. Yet, symptomatic of the cumulative damage of reputational revision, while I worked on her biography it proved impossible to persuade any major list to publish a new readers’ edition. Books, indeed, cannot speak for themselves.

“Why can’t a woman be more like a man?” Rex Harrison carolled, some 140 years after Barrett Browning asked herself the same question. Her answer, like that of many other pioneering women writers of the 19th and early 20th century, was that women are more like men than the elective “littlenesses” associated with that “One word Beth hated with her soul . . . ‘feminine’” indicate. In Britain in 2021 this is hardly news, yet posthumous deletion of cultural history continues. That gatekeepers tend to reproduce culture in their own image is a truism; that they might also do so retrospectively is too easily forgotten. This matters because of the work that gets lost. And because history is our role model.

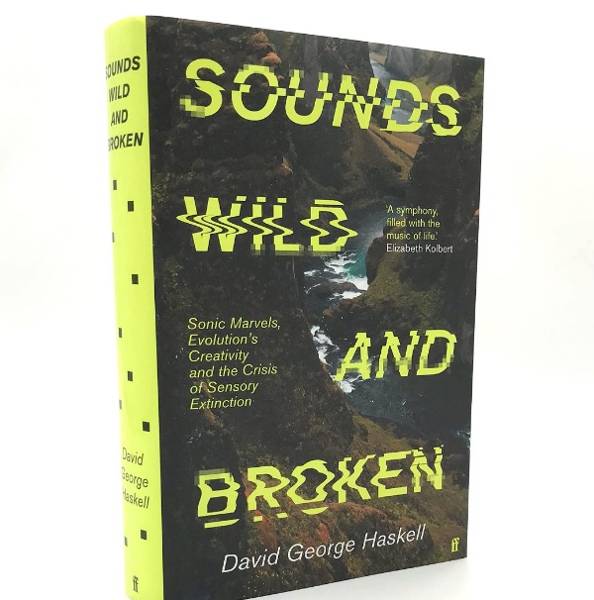

Fiona Sampson’s book “Two-Way Mirror: The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning” is published by Profile

This article is from the New Humanist summer 2021 edition. Subscribe today.