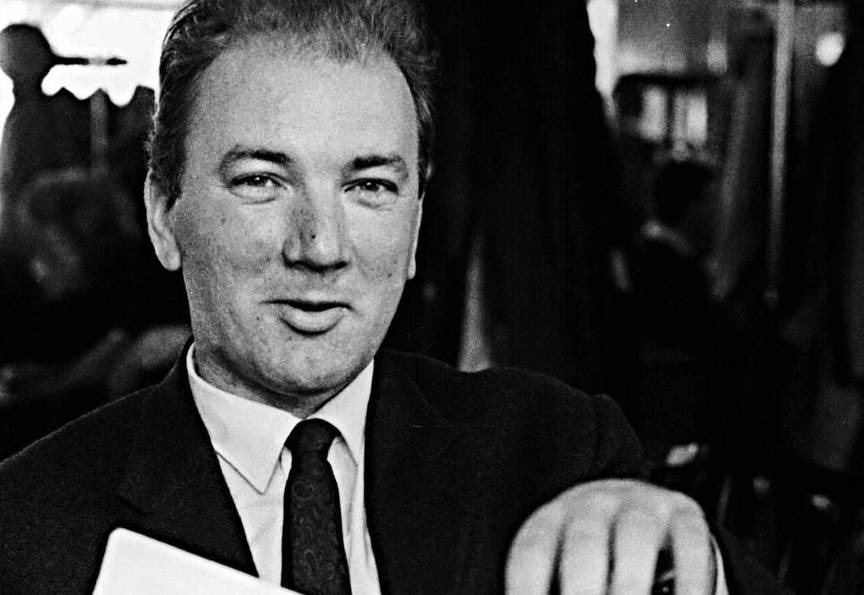

Books are frequently given and received as prescriptions: this one enlightens, that one cheers you up. Readers expect books to assist them in some way: to educate them, perhaps, or to deepen the moral sense. The books of the Austrian novelist Thomas Bernhard might be recommended as prescriptions too. Only they function as purgatives.

Bernhard, who died in 1989, is famous for the bleakness of his outlook. From his first novel, Frost, published in 1963, to Extinction (1986), the novelist and playwright developed a distinctive style and mode of cultural critique. His works draw attention to, and then revel in, the unremitting cruelty of human relations and the pretentious futility of cultural life. It is through this effect that they achieve their purgative function, inviting us to cast out all our attachments.

Most of Bernhard’s novels are now available in English translation and readers have been purging themselves with them for some time. They have been joined at last by The Cheap-Eaters, one of his shortest. For years it was hard to come by, having long been out of print in its previous translation. Now issued in a new translation by Douglas Robertson, it has been published by Spurl Editions, a California-based press who describe themselves as specialists “in works fitting for our current decrepit and apocalyptic world”. The Cheap-Eaters has clearly found a good home.

Much of Bernhard’s ire was directed against his own native Austria and was designed to make uncomfortable reading in that context. In his books, Vienna is a hateful place to live, representing the death of culture, along with the annihilation of art and intellect. Bernhard attacked Austria relentlessly as a country that he believed remained, following the end of the war, dominated by the twin spectres of Catholicism and National Socialism.

It is tempting to read Bernhard’s work biographically: this is the outlook of a man who was born illegitimately and whose father rejected him, who was schooled first by Catholic priests and then by Nazis (in his autobiography, he described school as “a machine for the mutilation of my mind”). Suffering from a chronic lung condition, he lived as a young adult among invalids, enduring botched medical interventions and the care of Catholic nuns. It is easy to see him as a tortured man, trapped in an ailing body, living with a death sentence and looking resentfully at the world around him. But this would do him an injustice. The themes in his work may be dark, but there is the sense that Bernhard is always there, in the background, laughing heartily at what he attacks. And besides, many of the themes covered in his work can be extended elsewhere. What makes Bernhard so persistently disturbing is that the world he depicts in his novels is often still recognisable, more than three decades after his death.

One recurrent theme is that of intellectual obsession. Bernhard’s obsessed intellectuals are great procrastinators. They have an epoch-making study in mind but never get down to writing it. Their commitment makes them ruthless to themselves and others, and because that work is never accomplished, there can be no possible justification for the pain it has produced.

A project of this type appears in The Cheap-Eaters, where Koller, the main protagonist, spends the entire novel attempting to write his Physiognomy, a great work in which important observations regarding the imprint of world history and nature and personal experience will be revealed through the study of facial features. The cohort for this study are the “cheap-eaters”, a group of men who for years have sat at the same table in the Vienna Public Kitchen, ordering the cheapest meal available. The intellectual challenge Koller has set himself is considerable. In order to bring his study to completion, he must hold the “entirety of nature and the entirety of the science of nature in his mind”. This simply cannot be done, and so Koller sets himself up to fail.

'Confronted by the inanity of everything ever written'

Another important theme in Bernhard’s work is the destruction of research subjects by their investigator, most brutally rendered in The Lime Works, published in 1970. A claustrophobic masterpiece, the novel follows the scholar Konrad and his disabled wife Zryd as they imprison themselves in an abandoned lime works near the Austrian town of Sicking. Konrad has them live there so that he can have the space, and peace, to begin writing his masterpiece, The Sense of Hearing. He submits his wife to his obsession with hearing, attempting to teach her to hear tiny variations in a phrase he mutters in her ear, each day, until she collapses with exhaustion. His lesson, which is also his experiment, ultimately fails, and eventually he ends it with a bullet.

The Cheap-Eaters is interesting for subverting this trend. Koller studies his subjects but does not cause them pain or discomfort. However much he inspects them, they go on eating easily alongside one another. Furthermore, when he first arrives at the Vienna Public Kitchen, Koller finds that they do not subject him to the intrusive inspection that he normally receives as soon as his prosthetic leg is noted. They do not confront him, as Bernhard writes, with “that common, squalid, and repulsive sort” of look “with which people like him are otherwise universally and incessantly confronted and to which they are exposed and subjected in the most vulgar and shameless fashion”. This does not mean that the cheap-eaters do not inspect him at all. Actually, they submit him to a “thorough and by no means squeamish inspection” as he eats. They see him clearly, but they do not judge his “crippled condition” or ask him to justify his existence, nor do they extend him any sympathy. They merely assist Koller as he attempts to take his seat. This suits Koller’s purposes perfectly, since his Physiognomy relies upon a similar gaze: an inspection of surfaces.

One character in The Cheap-Eaters, Goldschmidt – a bookdealer – presents an interesting mini-case study of Bernhard’s wider argument against the intellect. Committed to his work with books, he is also as a result confronted by “all the abominableness and brutishness of human history” that is contained within them. The bookdealer who takes books seriously “is the most pitiable person in the entire human race”, Bernhard writes, “because day after day and uninterruptedly he is confronted by the absolute inanity of everything ever written and more than any other person he experiences the world as a version of hell”. Language is itself irredeemable, from Goldschmidt’s perspective. According to what Goldschmidt tells Koller, language consists “of words of equal weight” by which thoughts are “incessantly weighed down and crushed”.

Against language, against intellectual culture

These are intriguing claims: against language, against books, against intellectual culture. But as with his other novels, logical argument is not the vehicle of Bernhard’s purging. Rather, through a reiteration and restatement of these claims, his writing offers its own peculiar respite.

Koller’s Physiognomy is never written, of course, and The Cheap-Eaters remains first and foremost an account of intellectual failure. Koller is an interesting example of Bernhard’s destroyed and destroying intellectual. Separated from others, existing superficially alongside his peers, he pursues his intellectual project with such diligent singlemindedness that he is unable to relate to other human beings. It is tempting to conclude that he cannot complete his Physiognomy because to study others, to speak of the human condition, is to account for the world intellectually. To do that is already to distort the world he perceives and to alienate himself from it.

The Cheap-Eaters is a magnificently annihilating little book. It presents an opportunity within the space of reading to become distant from the promises of intellectual culture that are made ever more insistently as they are betrayed. With Bernhard, the pleasure is in the purge.

This piece is from the New Humanist winter 2021 edition. Subscribe today.