Salman Rushdie has narrowly escaped the murderous attempt on his life by 24-year-old Hadi Matar. We don't yet know exactly what motivated the attacker. What is beyond doubt, however, is the blinding fury that drove Matar to jump on a stage in front of an audience gathered to hear Rushdie speak, ironically about the importance of protecting freedom of expression and the need for America to give asylum to exiled writers. For Matar to have slashed Rushdie several times in the neck, stomach and thigh, damage his liver and his eye in the few seconds before he was pinned to the ground speaks of a spine chilling frenzy.

What drove this frenzy? In a recent interview for the New York Post, Matar said Rushdie was “someone who attacked Islam, he attacked their beliefs, the belief systems.” A decade before Matar was born, Rushdie published a book: The Satanic Verses. The novel was perceived by some practising Muslims to be blasphemous in its portrayal of the prophet Mohammed and Islam. A year later, in 1989, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran issued a fatwa ordering Muslims to kill the author. The Iranian government retreated from the death sentence in 1998, but Rushdie still lived under the threat of attack, although this threat appeared to recede in recent years.

What is at stake today is not only about Rushdie, who is now recovering from what have been reported as "life-changing" injuries. It is also not simply about freedom of expression, much decried by some as a liberal aspiration which takes no account of the power axes that determine access to this freedom. It is about the right to dissent from religious orthodoxies. Rushdie has suffered for refusing to censor his writing on the religion of Islam. We should also remember that in many communities, it is women, young people and members of the LGBT community who bear the brunt of extreme religiosity.

Fighting religious extremism from within the community

Thirty-four years ago, when the fatwa was announced against Rushdie, the sound and fury was all about the writer’s freedom of expression. Southall Black Sisters (SBS), which I joined in that same year, was one of the first women’s groups to recognise the deeper significance of this fatwa for women’s rights. Our antennae had been honed by developments on the ground in London. More and more of the women who came to the centre were complaining of religious, rather than merely cultural pressures to conform. Sikh and Muslim gangs were getting into fights, each accusing the other of stealing their women in order to convert them. The previously cosmopolitan streets of Southall, in West London, were being choked off by processions during religious festivals and both Khalistani (Sikh) and Islamic fundamentalism were on the rise.

We felt that there was a third voice missing in the debate. While we fully supported Rushdie’s right to write, we felt the arguments put forward by the liberal establishment were tinged with racism against the backwardness of Muslims in Bradford, one of the largest communities of Muslims in the UK (the Bradford Council of Mosques had organised the book burning of The Satanic Verses). We wanted to challenge anti-Muslim racism but we also wanted to challenge the fundamentalist trends in our communities.

This seemed like a nuanced and logical position to adopt. But we were roundly condemned by the so-called secular anti-racist left, our erstwhile comrades. I remember asking a secular Pakistani writer friend of mine to act as interpreter for the meeting we were organising in support of Rushdie, to translate proceedings into Urdu. To my surprise, we had a huge row about it. Her position was essentially the same as we have encountered over the years right up to the Charlie Hebdo massacre in 2015 and beyond: that Muslims are a community under siege and now is not the time to point out their shortcomings. In a slightly different guise, this is the argument that we had faced on the foundation of SBS. We encountered opposition to our campaigning work against domestic violence, on the grounds that it exposed the underbelly of Asian communities to a racist "host" society. Now was not the time.

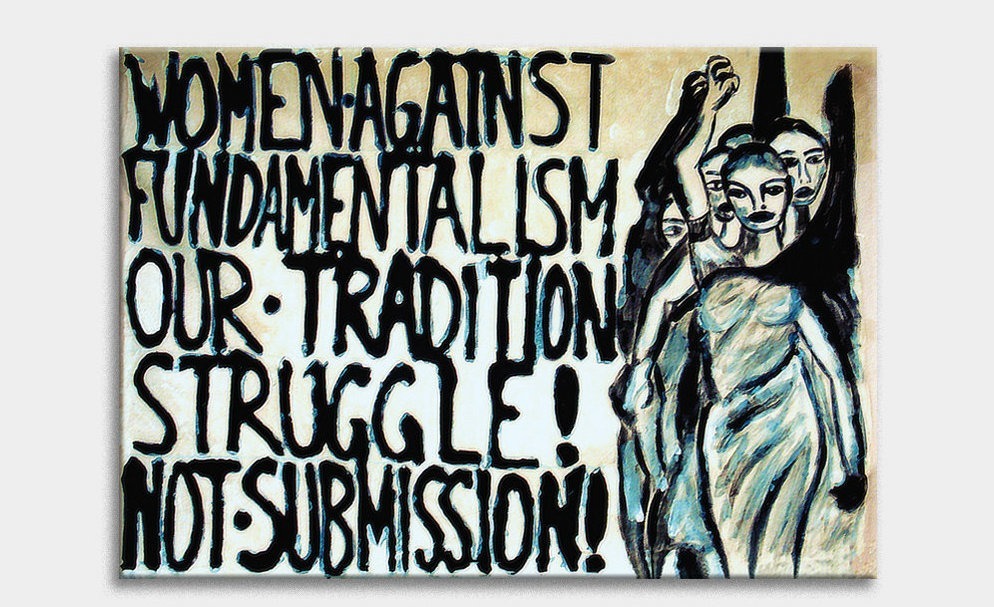

If not now, when? The birth of Women against Fundamentalism

We wanted to move forward with our work against fundamentalism, without feeding into anti-Muslim racism. In order to meet this challenge, we proposed a campaign against all fundamentalisms in all religions. In fact, that meeting in support of Rushdie in 1989 saw the birth of Women against Fundamentalism (WAF), a group of diverse women including Hindu women against Hindutva, Muslim women against Islamism, Jewish women against Zionism, Irish women against Catholicism and Sikh women against Sikh fundamentalism. These were the dissenting voices whose intimate knowledge of the traditions which had curbed their freedoms lent authenticity to the campaign.

That authenticity also put us in tension with "identity politics" – a trend which has since increased and is much worse today. When WAF was approached by the media for a comment on the Rushdie affair, we were always asked to send our Muslim members. When we campaigned against Hindus in London donating gold bricks to Hindu nationalists, the media were not interested. The focus was on Rushdie, and that's what they wanted to talk about. As a result, WAF came to be unfairly associated with anti-Muslim campaigning. Any attempts to point out the uneven interest from the media in our campaigns were countered with comments like we should have realised that the media would manipulate us. But that foreknowledge would not have stopped us in making the links between the forces that opposed Rushdie and women’s freedoms.

The Rushdie affair unsettled the political formations of the time. Nothing exemplifies this better than the WAF demo held in 1989. We assembled on the green opposite Parliament in protest against the young Asian men from Bradford who were marching to demand a banning of the book. These were men with whom we might have marched alongside, in previous years, to protest against police or state racism. Unknown to us, the National Front were also marching from the opposite direction – presumably not in support of Rushdie, but just to show aggression to a gathering of Asians. As soon as both groups of men spotted WAF, they lost interest in each other, their venom and focus turned on the women, swearing at them and trying to pull their placards off them. Who did the women turn to for protection? The police.

We need the courage to face our contradictions

The dangerous rise of religious fundamentalisms is in evidence around the world. The overturning of Roe v Wade in the US represented a victory for the anti-abortion Christian Right that has worked for years to take over the judiciary. In India, Hindu "cow" vigilantes have killed Muslim cattle traders in the name of protecting Hinduism’s sacred cow and beaten Muslim men accused of "love jihad", i.e. "luring" Hindu women into marriage. In the UK, Southall Black Sisters and One Law for All are fighting on many fronts. They have fought off an attempt by universities to segregate audiences by sex when religious speakers demand it. They have campaigned against informal Sharia courts dispensing second-class justice to women and have succeeded in getting the Law Society to withdraw its Sharia-compliant advice on drawing up wills.

WAF itself closed in 2012. Some of the women involved in it went on to found Feminist Dissent in 2016, a journal that is published annually with a focus on "gender, fundamentalism and related socio-political issues".

I would argue that the ground on which these arguments are taking place is even more slippery today than it was when the Rushdie affair began in 1998. We are living in hyper-sensitised times in which any challenge to religious beliefs can be deflected on the basis that it is causing offence. But there is no “right not to be offended” enshrined in the law.

We cannot keep turning the other cheek, saying now is not the time. Janus-headed, we need to look in all directions and face down the contradictory forces lined up against us.