In 1977, the German director Hans-Jürgen Syberberg released one of the most astonishing and challenging films of all time. Our Hitler: A Film from Germany is a vast meditation on the meaning of Adolf Hitler, not simply as an individual, but, as Syberberg tells it, as a phenomenon particular to Germany.

Running at nearly seven hours and shot entirely on a sound stage with a limited range of props, its four “episodes” use anything but a conventional narrative structure. There is no place here for what the script refers to as “the judicial realism of everyday life”, nor for the cosy conventions of film. This is not “a disaster film, but disaster as film”. Actors move between roles, talk to puppets (of Hitler, of Ludwig II), perform in front of film reels of mass gatherings, break the fourth wall again and again. Their voices compete with snatches of Wagner, Mozart, Beethoven and documentary recordings of actual speeches – Hitler at Nuremburg setting out his vision for Pax Europa, an interview with a woman just released from Auschwitz.

Sometimes these documentary voices are curiously intimate, such as Hitler – with what feels like genuine humility – thanking the German people for the trust they have put in him. Intimate too are the long sections where actors offer the real testimonies of some of the minor functionaries of the Nazi management team – the masseur to whom Himmler confided the worries that caused him to have tummy aches, and Hitler’s valet who talks of his

struggles to get the Führer to wear brown shoes with light suits, rather than his favourite old black boots. This is a film drenched in guilt and mourning, in which we are invited to share – but not as bystanders.

At the centre of the film is a single disturbing question asked by Syberberg of the German people (and therefore everyone): “What would Hitler have been without us?” Our Hitler is an exploration of complicity. Hitler, as Susan Sontag put it, is “depicted through examining our relation to Hitler”. Sontag, an American writer and philosopher of Jewish descent, called the film one of the 20th century’s greatest artworks.

Through this fractured, sometimes terrifyingly incoherent, sometimes terrifyingly coherent seven hours of celluloid, Syberberg attempts to do the impossible: to make a piece of art which represents that which cannot be faithfully represented. It is, like the three hammer blows to which Gustav Mahler resorts near the end of his Sixth Symphony, art at the very limits of its own intelligibility.

Capturing the reality of war

How do we represent the unrepresentable? It is one of the central challenges not only of art, but of history, journalism and all speech. How, in fact, do we represent anything in such a way as to not pervert it, let alone to capture its “truth”? Is it even possible to talk about an “anything” which exists before we represent it? And if we can, what rights and obligations do we have? This is not a new problem, but seems to come to us newly minted with every new conflict and every new technology used to “capture reality”. All history is, ultimately, revisionist: events (what happened) and their representation (what we say happened) are two different things.

For the historian, this is the problem of “emplotment”, to use a term coined by the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur and later taken up by American historian Hayden White in books such as Metahistory (1973). By describing any act, situation or event, whether in art or any other medium, including “realism”, we immediately impose a narrative structure. In particular we impose a point of origin, a point of transition, and in most cases a point of conclusion. Or to put it simply: a beginning, a middle and an end. Art does this, but even the simplest descriptive act imposes this structure: “Today I went for a walk”.

Emplotment can never, White argues, be a neutral act. To posit a “beginning” is to choose a starting point which, however arguable, is in the end arbitrary. Moreover, it imposes a causality which can give the event or events a sense of inevitability. To posit an “end” suffers from the same problem, while the “middle” takes strands of a particular situation, suppresses those deemed unimportant and draws connections between them. The world becomes a series of eras and sub-eras – the Industrial Revolution, the Second World War – and these divisions are themselves battlegrounds.

When any “chronicle” of events – itself necessarily selective – becomes a “story” this cannot help but impose a coherence. Historical writing is, in its nature, a system of explication. Nothing is allowed to be inexplicable. Even the judgement “this is inexplicable” is a type of explication, positing a set of assumed rules which this example is deemed to fall outside of.

For White, it is art that opens the possibility of presenting the inexplicable. His example is Art Spiegelman’s Maus. Serialised in the 1980s, Maus is a comic book that uses postmodern techniques, representing Jews as mice and Germans as cats, using a mix of memoir, history and fiction. Maus, according to White:

“presents a particularly ironic and bewildered view of the Holocaust, but is at the same time one of the most moving narrative accounts of it that I know, not least because it makes [through its framing device] the difficulty of discovering and telling the whole truth about even a small part of it as much a part of the story as the events whose meaning it is seeking to discover.”

That Maus has again become part of the battle over culture in the United States – recently being banned from schools in Tennessee – is no surprise.

This faith in art is shared by Syberberg. Adolf Hitler, “the most important topic of our history”, must be tackled by art as, the film argues directly, both political theory and historical research are inadequate to the task. History is not always written by the victors, but it is always written in a victorious form: that of the coherent narrative. That art can escape this obligation is the hope of Syberberg’s film.

This is Nietzsche’s insight too. In his Birth of Tragedy, he argued that it was the Greek genius to create, in tragedy, an art form which, as White phrases it, “depended on man’s mythopoeic faculties, his ability to dream . . . in the face of his own imminent annihilation.” This was done not to “capture reality” but “in the full consciousness of the fictive foundations” on which meaning rests. Life is, in itself, meaningless. It must be transformed in a way that gives it meaning. An art that “imitates” nature is no art. It is the act of transformation which gives humanity any chance at transcendence.

This is the beauty, Nietzsche argues, of the tragic form – it lifts the protagonists out of their meaningless existence, but ultimately returns them to it. If Theodor Adorno wrote that it is barbaric to write poetry after Auschwitz, this is a barbarism that for Nietzsche is both necessary and a form of affirmation. Poetry – art – endures.

Ukraine and the atrocity exhibition

And yet, this margin between art and what we might call non-art has become increasingly confused and disputed. As videos pour out of Ukraine in real time, analysed by thousands of citizen journalists for their veracity, and for intended and unintended clues regarding locations, troop strength, weaponry and victim counts, we are drenched in images in a way that even Nazi propagandists could not have imagined, could not have dreamed.

We find ourselves immersed in a world of competing narratives, not only between the two sides of the conflict, but within each side. The sheer volume of stories, the relentless nature of their telling, and the ravenous beast that is the newsfeed means that everything is both flattened (there is too much of it to make anything meaningful) and overdetermined (everything is meaningful, all the time). It is, in J. G. Ballard’s phrase, an “atrocity exhibition”. We can move around the gallery at our leisure, deciding whether each exhibit is shocking or beautiful; neither, or both.

Syberberg’s narrator argues that “whoever controls the films controls the future”. Once the war started, Hitler spent his evenings viewing only propaganda films and newsreels. No newsreel could be released until after he had seen it and edited the text. Thus the war, Syberberg’s film argues, was in one sense a home movie being directed by Hitler – making him, the narrator says deadpan, “the greatest film-maker of all time”. Since then, of course, technologies have changed, meaning that propaganda films are more quickly produced and more easily manipulated. Deep fakes of both Vladimir Putin and Volodymyr Zelensky, made by new technologies, immediately started circulating, while war zones are manipulated in order to support the narrative of victory or defeat which suits the propagandist. A press image of a line of tanks on a road outside of Kyiv near the start of the conflict was pored over for weeks, generating as much secondary literature as Picasso’s “Guernica”.

Truth in conflict

Truth is a supple thing in war. The state’s ability to produce a narrative – a “mythos” in Nietzsche’s telling – which provides a justification for its goals, while inflating its victories, has been vital. These justifications might be immediate or historical (such as Putin’s essay on Ukraine as part of Russia) and this is just as true for democratic and totalitarian regimes. Much of the Cold War was a propaganda war, with both sides producing versions of the battle to fit their narratives. These days, Stalin’s painstaking erasure of “traitors” from photographs can be achieved within seconds by an eight-year-old, let alone the numerous government and nongovernment organisations dedicated to the task.

In one sense this becomes a zero-sum game. The sheer level of information cuts across any emotional response. As Stalin put it, one death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic. When the history of the war is written there will be the columns of the dead and we will, to use Nietzsche’s phrase, “settle accounts”, see who won and lost. “The war is not even over,” writes Nietzsche, “before it is transformed into a hundred thousand printed pages and set before the tired palates of the history-hungry as the latest delicacy.”

Worse, as he puts it, our next step is to enter the realm of the “once upon a time”. Inevitably, films will be made, churning out the tropes of the war story – letters home, tight-knit squadrons, the soldier who can stand no more. The meaning of each individual victim will be narrowed to a part of some great narrative. The inexplicable becomes explicable. We will be assured that lessons can be learnt, and be agog again when they are not. Or, as White put it, “The notion that sequences of real events possess the formal attributes of the stories we tell about imaginary events could only have its origin in wishes, daydreams, reveries.” Perhaps the greatest of all desires for wish fulfilment is a sense of coherence. Perhaps a sense of coherence is most desired in extreme events such as war. Especially, perhaps, when the war is lost.

An impossible ending

But war is not coherent. It is the onward surge of millions of individual actors, performing roles which they both learn and improvise. If we are fortunate enough to be able to look back at “the Ukrainian War” of 2022, or watch biopics of the heroes or the villains, it is this dreadful incoherence we need to remember.

Syberberg attempts to make us remember, but how can he do so while deciding on an end to the film? After close to seven hours, he appears defeated by this task. First, we see his own daughter perform several scenes of culmination – gazing at stars, removing a black tunic to reveal a white one, looking at the camera and away from it – each of which he seems to deem inadequate. As Sontag puts it “Though Syberberg tries to be silent (the child, the stars), he can’t stop talking; he’s so immensely ardent, avid.”

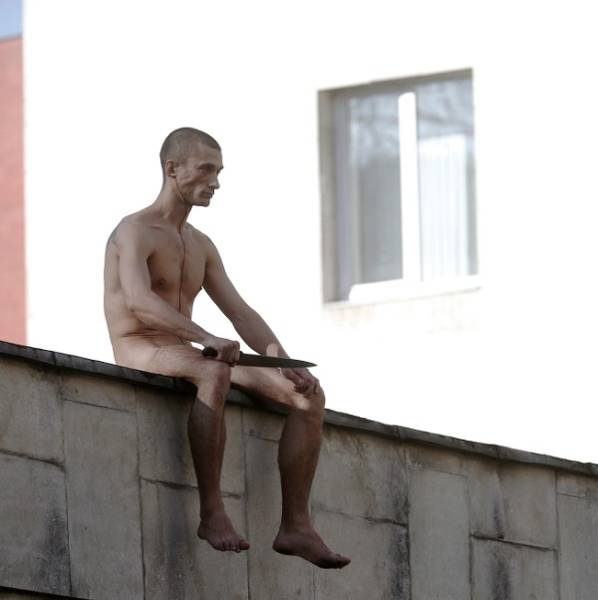

Syberberg is also caught in the trap of what Saul Friedlander has called the “aestheticisation” of the Nazi epoch. This started with the films of Leni Riefenstahl, such as Triumph of the Will, which fetishises the rallies, the uniforms and the Aryan type, tempting the viewer to become complicit in its beauty. All art forms grapple with this danger, but the cinematic aesthetics of Nazism – its erotics – has its own complex power. Riefenstahl’s films are of a piece with Hitler’s own erotics. But real-life brutality is shabby, not salacious.

So, do we end in hope or despair? The music shifts almost guiltily between the end of Wagner’s Parsifal (redemption, possibly) and Beethoven’s Ode to Joy (hope, maybe). Then the text of Corinthians 13:2 appears (“though I have faith so I could move mountains and have not charity I am nothing”), followed by a single phrase in three European languages – “Der Gral, Le Graal, The Grail”. Does this represent the end of a quest or the quest itself? As with the music and Biblical text, the meaning is enigmatic.

In casting about for an appropriate end to the film, Syberberg shows his own defeat. Even after seven hours, the film wishes to keep going, to keep turning Hitler about in its hand; to resolve without resolution; to explicate, while remaining inexplicable; to solve the insoluble.

This piece is from the New Humanist autumn 2022 edition. Subscribe here.