Several of my ageing friends are moving house. Ian McDonald, who always seemed as much a part of Chelsea as the King’s Road, is upping sticks and heading for a largely unpronounceable dwelling in the north of Scotland. Meanwhile, Geoff Holdsworth, who always appeared as settled in Soho as The French House, emails me to say that he is returning to his roots in Leicester. One can readily understand these moves as a desire for a second childhood. Having been out in the big wide world for most of their adult lives, these good old friends of mine are now saying goodbye to the supposed artificialities of London life and returning to what they conceive of as the simple authenticity of their formative years.

I’m unlikely to follow them. Not because I lack sentiment about my childhood homes. I can readily conjure up happy visions of walking through the vast open spaces of Sutton Park or taking a bracing dip in the brown waters of the River Mersey after a picnic on Crosby beach. But I’m now far too old to imagine that I might be allowed to enjoy the indulgence of any more lifetime experiences. This is my last life on Earth.

This, of course, is the whole problem with atheism. It robs you of the delightful possibility of an after-life. I believed years ago, with an absolute Catholic certainty, that my final days would not be spent in a Scottish croft or a suburban Leicester villa, but in a resting place for my Christian soul. From an early age, I reckoned that place would be Purgatory – a realm reserved for minor sinners, and a relatively pleasing prospect when compared to its infernal alternative.

However, in Catholic theology, it was not a particularly well-defined location. Heaven, by comparison, was well documented. There would be clouds to sit upon, harps to strum and a diet of milk and honey to be enjoyed in the blessed company of saints and martyrs.Hell, if one excludes Dante’s poetical cornucopia of horrors, was even more straightforward. It was hot. Very, very hot. Burning hot. But not quite hot enough to consume you and thereby end your suffering. Purgatory, though, lacked all such detail. There was no promise of happy harpists or fork-tongued devils, but only the prospect of a somewhat barren landscape in which you were required to wait and wait until your sentence was deemed to have been served, your sins to have been purged.

The great problem with Purgatory was the length of that sentence. It was not eternal, like Heaven and Hell. One could hardly go on being purged for ever. But were we talking months or years or decades? Fortunately, there was some clarification in the Catholic catechism. Here, one learned that the regular recital of certain prayers and regular attendance at acts of devotion might reduce your sentence by an explicit number of days. Three carefully recited rosaries earned an indulgence – a time-off for good behaviour bonus – of precisely 28 days. There it was, in neat brackets, in my personal catechism. I can clearly recall the childhood years when I would systematically tot up these indulgences in order to effect a speedier transit to eternal bliss.

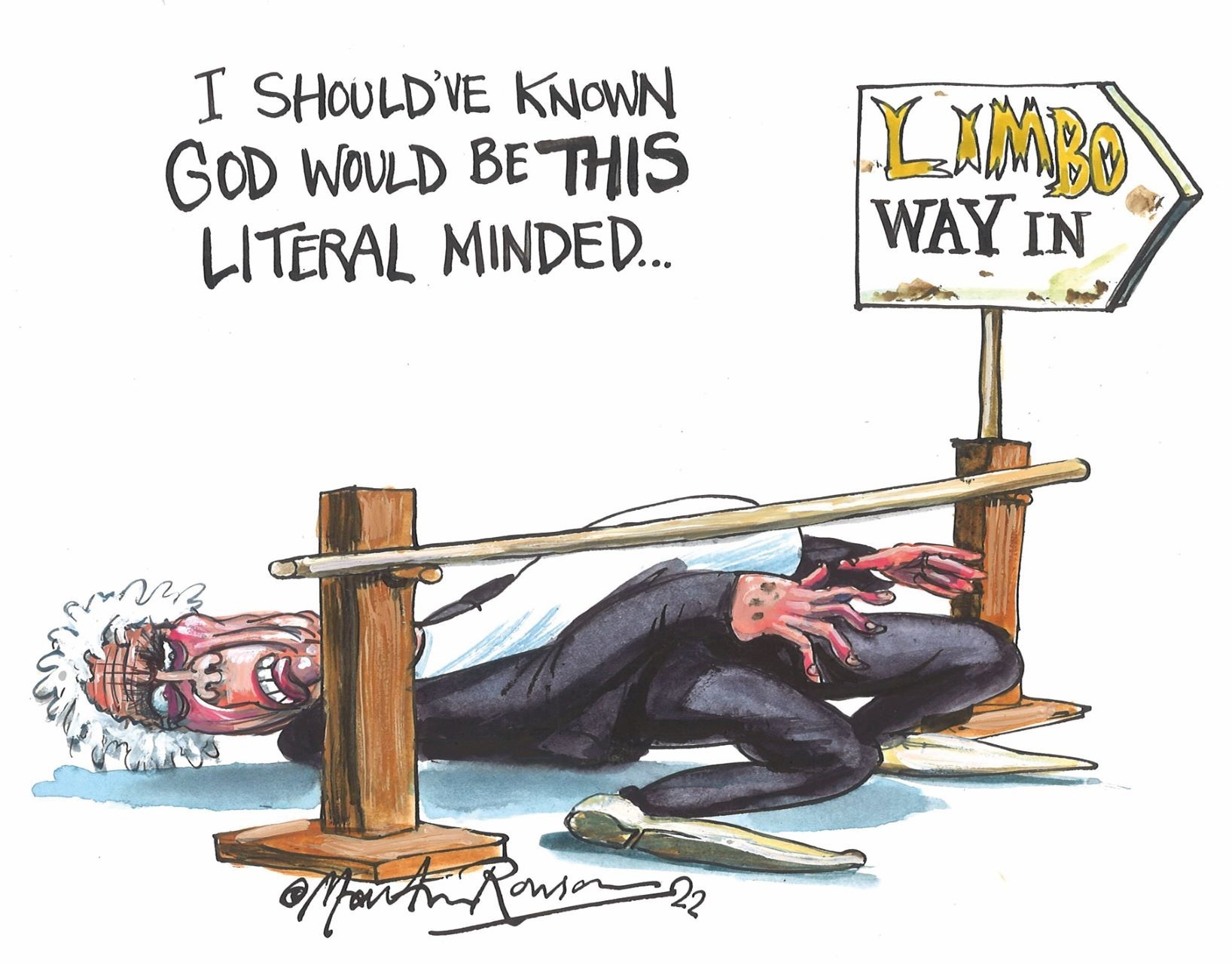

As an unbeliever, thankfully, I have one last hope of securing eternal life in Paradise: entrance into Limbo. According to Catholic teaching, this is a special part of Hell for those who were born before the birth of Christ. These unfortunate individuals never had the opportunity of gaining the usual visa requirements by being baptised into the true faith. Now, I was hardly born before the birth of Christ. However, according to my mother, I was baptised by a rather simple-minded and somewhat tipsy priest who apparently announced at the service that “Florence” Taylor was now “a child of Christ”.

Might that mere slip of the tongue get me off the hook? Detach me from the devil’s fork? Allow God to overlook all my years of disbelief and blasphemy and unrelenting sinfulness? Usher me into Paradise? I’ll do my level best to let you know.

This piece is from the New Humanist autumn 2022 edition. Subscribe here.