Britain’s Jews: Confidence, Maturity, Anxiety (Bloomsbury) by Harry Freedman

The recent release of the 2021 England and Wales census figures for religion and ethnicity led to the usual debates about who “we” are now. While particular findings attracted attention – most notably, that self-identifying Christians are now in the minority – the census holds a deeper allure. By describing the population as a series of coherent, easily identifiable groups, it holds out the comforting promise that we might be able to understand the messy diversity of this nation (or nations).

This desire to “fix” the population, to pin the butterfly, conceals much harder questions as to how we might come to comprehend the collective identities that people actually hold. The case of British Jews – the ethno-religious group I both belong to and write about – is particularly illuminating. The contrast between what people think they know about Jews and what they actually know is often perilously stark.

There’s a paradox in how Jews are made visible in contemporary Britain. On the one hand, we have never been more present in national debates than in the last decade or so, largely due to debates about antisemitism. Individual British Jews – from comedian David Baddiel to historian Simon Schama – are more visible and more talkative about their Jewish identities. Yet this visibility conceals much of who British Jews actually are. Jews are visible if they are strictly Orthodox men in black hats, if they are defiantly secular media personalities, or if they are campaigning about antisemitism. Beyond that, the great mass of Jewish life is usually invisible.

Harry Freedman’s new book Britain’s Jews: Confidence, Maturity, Anxiety helps to fill in the picture. Volumes that take an overview of contemporary British Jewish life as a whole are surprisingly few (Turbulent Times: The British Jewish Community Today, which I wrote with Ben Gidley, came out in 2010 and was the first book-length sociological study of the community in decades). That means that Freedman can’t take anything for granted about the background knowledge of his non-Jewish readers. He writes clearly and knows the community inside and out, but the book is full of detail that readers may find engrossing, but which they might equally find dull or simply odd.

The British Jewish community contains a bewildering alphabet soup of organisations. Explaining the difference between the Liberal and Reform movements is a challenge even for their rabbinic leaders. Given that organisations like the Board of Deputies or the Chief Rabbi are often the targets of non-Jewish (and sometimes Jewish) suspicion, it’s essential to go into some detail as to whom they do or do not represent. But I felt a nagging anxiety that Freedman’s guide to the community’s structures might tax the patience of the reader.

Perhaps the confusion inherent in conveying this array of organisations and their arcane politics is the point – maybe that is actually what being Jewish is. But to convey that reality in a compelling style may be a challenge too far. At the same time, as someone who has worked in the British Jewish community for many years, I inevitably noted which individuals and Jewish organisations Freedman doesn’t mention.

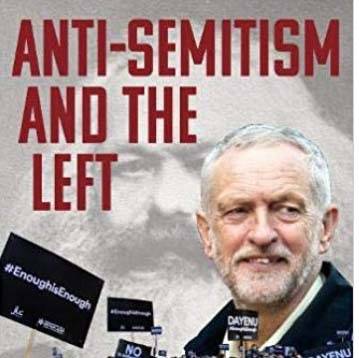

In fairness, Britain’s Jews is not intended as a comprehensive guidebook. Freedman has a larger theme that he wishes to explore: the seeming paradox that Jewish life in Britain seems to be thriving, at the same time as British Jews are increasingly speaking publicly about antisemitism. The struggles with the Labour Party during the Corbyn years saw an unprecedented institutional effort across the Jewish community to articulate its concerns in vehement terms (with, of course, a significant proportion of Jews dissenting). This was the action of a self-confident and well-organised community. The duality has bewildered and sometimes angered many non-Jews, particularly on the left.

This is an exceptionally sensitive issue and Freedman’s overall positivity about Jewish life in Britain has been received with some murmurs of disquiet within the community (both about downplaying the threat of antisemitism and about not giving enough attention to the more problematic aspects of the community). There are old fears at work here: that a complex picture of Jewish reality will undermine the unified messaging that Jews require to survive.

There’s no way around it, though. Some aspects of British Jewish life do seem odd to outsiders. Freedman demonstrates the common (if slowly declining) tendency of British Jews to belong to synagogues whose values they do not actually share. Most members of the United Synagogue – the largest Orthodox body, whose spiritual head is the Chief Rabbi – are not themselves Orthodox. It is as if secular liberals chose to affiliate to the evangelical branch of the Church of England.

In his attempt to capture what everyday Jewish life actually feels like, Freedman quotes his interviewees at length. But the book was written during the pandemic and the Zoom interviews don’t compensate for the lack of portraits of the spaces in which Jewish life is lived. This is important, as the aspects of that life that may seem bizarre to outsiders make much more sense when you see them “in action”.

Reading Britain’s Jews made me wonder whether my own understanding of other ethnic and religious minorities might be shaped by accounts that leave out the texture of everyday life. While reading books can provide a starting point for understanding what it is to be Muslim, Sikh or Afro-Caribbean in Britain today, they are no substitute for the experiential knowledge that we need to understand the other more deeply. Without the texture of everyday life, all we are left with is a much more detailed version of the kind of knowledge that the census provides.

This piece is from the New Humanist spring 2023 edition. Subscribe here.