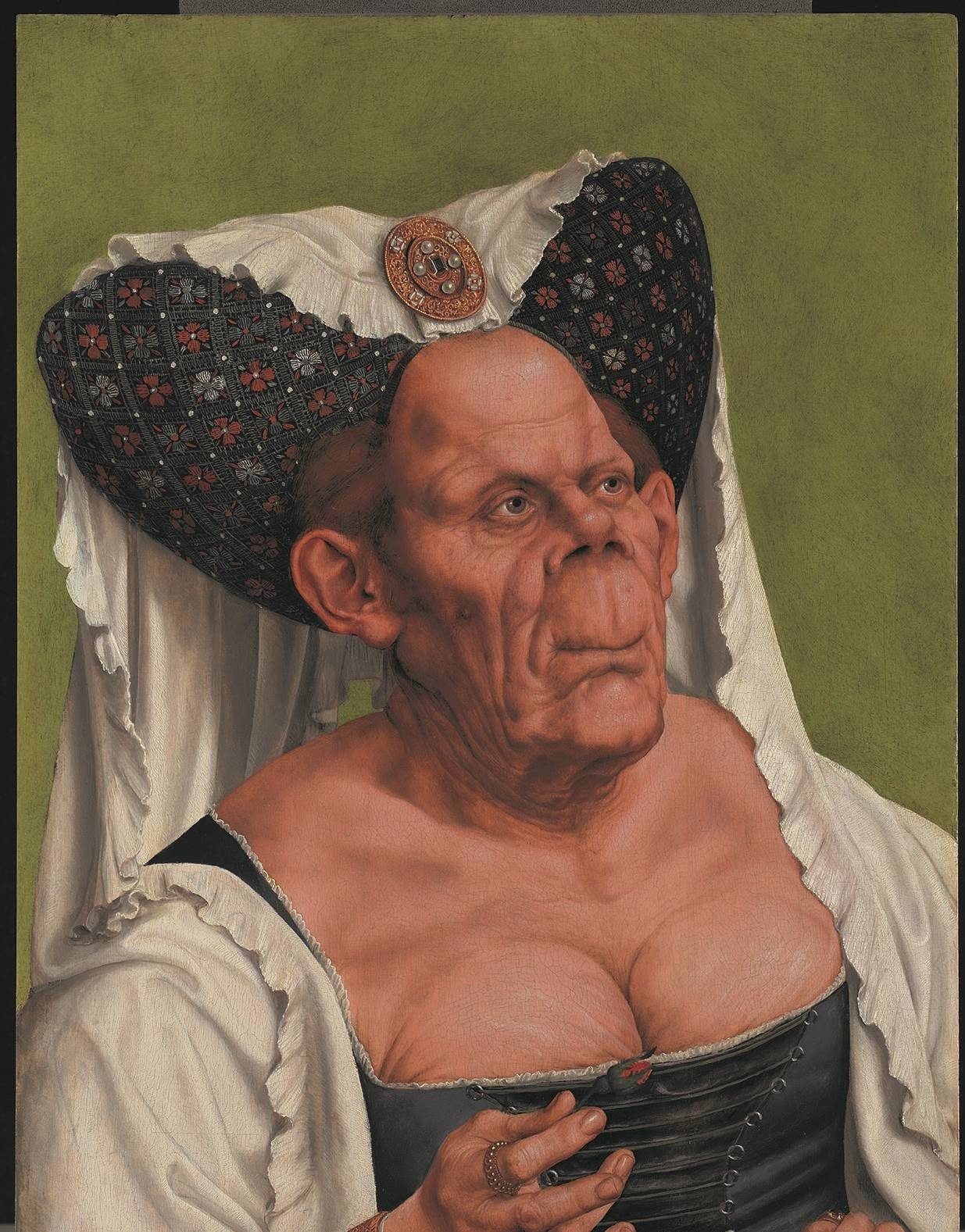

It is said that the ancient Greek painter Zeuxis died while laughing at his completed likeness of an ugly old woman. The Flemish artist Quinten Massys survived the painting of “The Ugly Duchess” (about 1513), but it might have been a close shave. Certainly plenty of people have at least smirked at her in the years since.

This is because, and there is no getting around it, she appears ridiculous: bulging forehead, protruding ears, puckered mouth, hairy mole on her cheek, huge horned headdress and shrivelled bosom. She looks beseechingly upwards, clutching a tiny withered rosebud. When the painting was put up for auction in 1920, the New York Times advertised the sale of a “portrait which is generally accepted as being the ugliest one in the world”. But why is she ugly? And how are we meant to respond?

A new exhibition at the National Gallery in London called “The Ugly Duchess: Beauty and Satire in the Renaissance” successfully answers these questions. It traces the influences on and atmosphere around the conception of “The Ugly Duchess” – religious, artistic, misogynistic – and convincingly places her within a long tradition of negative portrayals of women. There are witches, crones and hags; the incredible grotesques of Leonardo da Vinci; and the creepy John Tenniel illustrations for the 1865 edition of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. All either influences on, or influenced by, Massys’ duchess. It is to the considerable credit of this exhibition that it hasn’t dampened the fun of these artworks, while brilliantly elucidating the sinister threads that run through them.

The first thing that we discover is that the duchess has a partner. A man. Apparently, they were conceived as a pair, then separated and lost to each other for many years. Reunited, they make an odd couple. For one thing he looks remarkably unremarkable, even dull. He is seen in profile wearing a dark velvet cap and dark fur-trimmed coat. He looks prosperous and respectable. He has full lips, heavy lids and a bland expression, with one hand held up towards the duchess. Plainly, an exchange is taking place: his outstretched hand is a response to her proffered rosebud.

The exhibition makes clear that this was a familiar trope. The accompanying catalogue informs us that “The advent of print culture in the second half of the fifteenth century expanded the repertoire of secular imagery and propelled humorous subjects deriding what were then considered society’s ills.” One such target of satire was the so-called “ill-matched couple” – usually a wrinkled woman or wizened man who is courted by a much younger partner desirous of their wealth. A brilliant example of this genre is provided in the form of an engraving by Israhel van Meckenem called “The Unequal Couple” (about 1480–90). A corpse-like woman looks deep into the eyes of a beautiful young man with flowing locks, while his hand travels over the large bag of coins she is clutching.

Our couple exhibit more dignified behaviour, yet they too would have been immediately identified as ridiculous. The man (possibly based on the vastly wealthy Cosimo de’ Medici) is cast as a recognisably smug banker-merchant type, while the woman (rumoured to have been based on the famously ugly Margaret, Countess of Tyrol) is cast as a recognisably freakish grotesque – a stock character borrowed from Leonardo da Vinci’s visi mostruosi (monstrous faces). Her likeness appears again and again in different works by different artists – in Florentine engravings, English misericords and French illustrations. In each she is a figure of either fear or fun.

One cause for ridicule is her outfit. The outsized headdress and revealing corset, in what was then an outdated and vulgar style, would have immediately marked her out as the “embodiment of foolish vanity”. The great philosopher Desiderius Erasmus (Massys’ contemporary and patron) had especial contempt for such overdressed women: “Who would put up now with a decent married woman wearing those huge horns and pyramids and cones sticking out from the top of the head and having her brows and temples plucked so that nearly half her head is bald?” On seeing such a figure “Everyone would laugh and boo.” Clearly, in the 16th century, such a get-up was familiar visual comedy: the delusional old woman, full of lust and avarice, mutton dressed as lamb.

But amid all the laughing and booing there is also a palpable unease. This is perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the exhibition. Old women, their representation made more visceral by the period’s furtherance of verisimilitude, are here often depicted as sagging, cackling hags. Due to religious and folkloric superstitions and misunderstandings over how the female body works, there had developed a pervasive fear of women – in particular, fear of their sexuality. Malleus Maleficarum (or The Hammer of Witches, first published in 1486), a treatise written by German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer, declared that “all witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable”.

This concern can be seen in Massys’ sly-looking, overdressed hags (those horned headdresses are a sure sign of devil worship), but it finds its battiest representation in the wonderful engraving “Morris Dance with the Sausage Woman” by the Italian Monogrammist SE. Here, we behold a woman much like the duchess who holds in one hand a spear of phallic sausages and in the other a satanic cloven hoof, while a group of men dance around her.

In this image, and elsewhere, older women are depicted as worryingly powerful – as enchantresses, seducers and subverters of men’s rightful position. The most exhilarating example featured in the exhibition is Albrecht Dürer’s “Witch Riding Backwards on a Goat” (about 1500). An old, half-undressed woman with sagging breasts and an expression suggesting a full-throated war cry soars across the page on the back of a black, horned goat, scattering four cherubim in her wake. Her hair eerily flows in the opposite direction she is travelling and she suggestively grips the goat’s horn. In this disconcerting image of disorder and rebellion there is little for the male viewer to chuckle at.

In The Witch as Muse: Art, Gender and Power in Early Modern Europe, Linda Hults observes that “The sexual drive was believed to be greater in postmenopausal, widowed women. Their sexuality was especially repugnant not only because of their physical appearance but also because it could not lead to procreation.”

It is interesting that Massys’ “ugliest” portrait should have an afterlife as the frightening duchess in Alice in Wonderland (beater of babies and owner of the Cheshire Cat). While not mentioned in the exhibition, the portrait also bears a resemblance to the witch in the Studio Ghibli film Spirited Away. She becomes, in these new guises, divorced from the real-life fears and prejudices that shaped her in the first place. She is just a scary template. What is affecting about the items collected at the National Gallery is that they remind us of the uncomfortable themes beneath. In their laughter, sadness or fury, the paintings reflect something in the viewer. Perhaps a guilty conscience.

The exhibition holds out the promise of discovering a duchess who is not only grotesque, but also “subversive, fierce and defiant”. While the curators have gamely tried to reposition her as a more actively destabilising presence, this is ultimately unconvincing. Like it or not, the joke is entirely at her expense. “The Ugly Duchess” was conceived and executed amid titters, for an audience that was looking for a laugh. Although now, in this concise but wide-ranging exhibition, she might finally be in more sympathetic company.

This piece is from the New Humanist summer 2023 edition. Subscribe here.