In June, Northern Ireland introduced opt-out organ donation, finally joining the rest of the UK. This means that adults are considered to have given their consent to be a potential organ donor after their death unless they specifically say they don’t want to be.

The change will likely save many lives. Ten to 15 patients die each year in Northern Ireland while awaiting a transplant. Currently, there are around 150 people on the waiting list. The new law is named after six-year-old Dáithí Mac Gabhann, who has been waiting for a heart transplant for five years. His family fought for the change in law, alongside campaigners who pointed out that 90 per cent of people in Northern Ireland supported organ donation but only half were signed up to the Organ Donor Register.

The trend towards opt-out across the UK mirrors the rest of Europe. Most of the continent has now shifted to an opt-out system. However, when it comes to advancing organ donations, the evidence shows that opt-out legislation is often insufficient on its own.

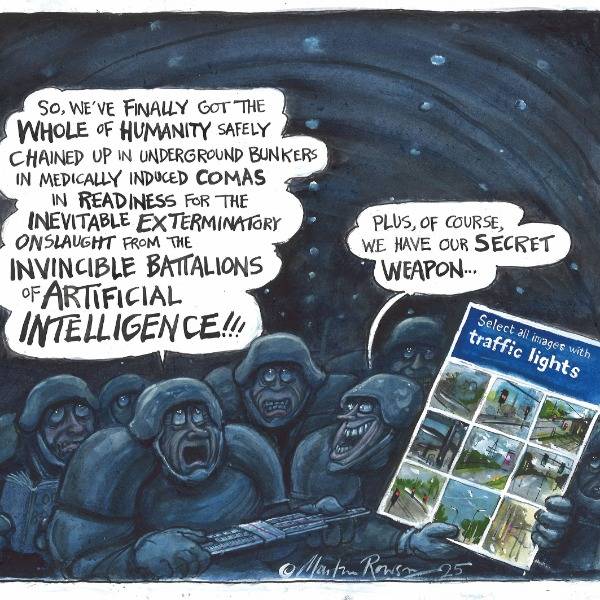

Public education is key. Under soft opt-out systems, like those in the UK, family members can intervene to block a donation after a relative’s death – this often happens because families aren’t sure what their relative wanted, so it’s important that people talk about their beliefs and intentions. But above all, systems to identify opportunities for donations and good matches with patients need to be improved. That could take many forms, including new technologies. The National Institute for Health and Care Research and the NHS are helping to fund the development of a system using artificial intelligence. Researchers believe that AI could prove more effective than surgeons at examining donor organs and assessing their suitability for transplant.

The team estimates that the new system could result in up to 200 more patients receiving kidney transplants and 100 more receiving liver transplants every year in the UK.

The move towards opt-out organ donation is a positive sign of societal progress. Increasing the availability of organs for donation will only become more important as our populations age, meaning that a lower percentage of organs will be suitable for transplant. Demand always outstrips supply, and we must carry on doing what we can, whether through changing legislation, public awareness or technological progress.

Organ donation saves lives, and anything that helps one more organ reach a patient in need is a change worth fighting for.

This article is a preview from New Humanist's autumn 2023 issue. Subscribe now.