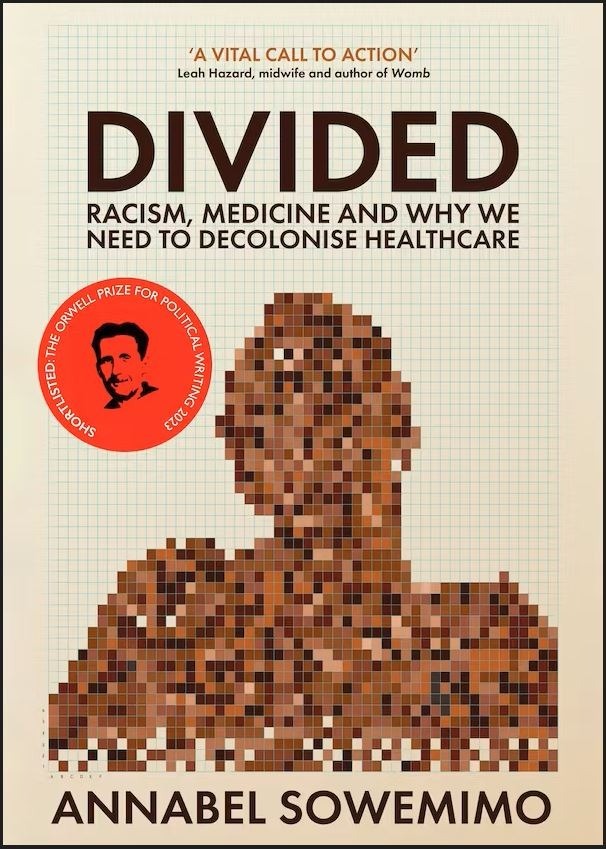

Divided (Wellcome Collection) by Annabel Sowemimo

The health service is a contradiction. It has been built on immigrant labour from conception to the present day. Walk into many NHS services, and you will find it is Black and Brown faces that are assessing, diagnosing and treating. Yet we find huge race-based health disparities, in maternity, mental health, Covid-19 deaths and more.

Dr Annabel Sowemimo is a sexual and reproductive health registrar. She has spent years rotating through the health service as a junior doctor, working in everything from A&E to community clinics. Her father was a doctor, her grandmother a nursing auxiliary who moved from Nigeria to work in the then fledgling NHS. Divided is her debut. It is a mix of statistics, clinical vignettes and historic facts. Meticulously researched, the book attempts to explain how white scientists of the past have contributed to the racial biases that infiltrate health services today – from the eugenicists determined to prove that those with darker skin were substandard, to pioneers who developed treatments and diagnostic tools with white patients in mind.

There are plenty of examples of past exploitation: the testing of the contraceptive pill on Puerto Rican women, the Black women whose bodies were experimented on, and many others, highlighting the debt that medicine owes. Moving forward into the modern day, we see the textbook Nursing: A Concept-Based Approach to Learning, published in 2017, splitting patients into racial categories detailing how they managed pain based on ethnicity. Muslims, it said, would want to endure pain as a test of faith. Jews would be vocal and demanding, and Black people would report higher intensity pain than all the others. White patients were not grouped into any bracket. The book was withdrawn from circulation after an online protest, but Sowemimo argues that its approach exemplifies a more general problem across most medical textbooks: white people are the standard to which all others are compared.

Divided starts with history lessons and theoretical problems, and moves on to illustrate how these racial biases can contribute to patient deaths. Three years ago, a national report on maternity services found that Black women were four times as likely to die as a result of pregnancy complications, compared to white women. Asian women were meanwhile twice as likely as white women to die or be injured. In mental health cases Black patients are four times as likely, and Asian patients twice as likely, to be detained compared to their white counterparts. Pulse oximeters, which measure oxygen levels in the blood, are less accurate on darker skin, potentially compromising care. The metrics and medical ranges used to distinguish what is normal are based on white patients.

Statistics are peppered throughout the book, alongside Sowemimo’s personal accounts. She has witnessed children misdiagnosed, Black women who are in severe pain and heavily bleeding ignored, and health colleagues reiterating the myth that black skin is more resistant to pain compared to others. The reader may question whether this is all down to race or other factors. It is difficult to say with isolated anecdotes, but Divided goes further than this, showing how these issues are well documented, systemic and too often unchallenged. The facts speak for themselves.

Divided deserves a large readership. Weighty problems are raised, but practical and realistic changes are proposed, too. Health professionals should be educated differently, says Sowemimo; new metrics can be used; health data and technology can address some of these biases.

The solutions that Divided presents may be limited, but it achieves its main purpose – to ask the question, to make the case for answering it undeniable, and to open up the conversation.

This piece is from the New Humanist autumn 2023 edition. Subscribe here.