In common with other young Catholic boys, I spent long hours on my knees saying prayers for departed relatives. “Don’t forget to pray for your Uncle Leslie,” Mother would call as I climbed the stairs to bed.

This always seemed an odd injunction because I knew only too well that poor Uncle Leslie had been thoroughly dead and buried for the best part of 10 years. But Mother constantly reminded me that he had hardly led a blameless Catholic life, what with his three marriages and that rumoured affair with a Parisian nightclub hostess. He would, therefore, have been sentenced by God to years of atonement in Purgatory before being airlifted to the Elysian Fields. Only regular prayers could ensure that his purgatorial residence was relatively short-lived. No more, say, than a few years.

Mother could speak about time in the afterlife with such specificity because of the Catholic catechism’s readiness to attach precise periods of atonement to distinctive sins. As I recall, a purgatorial term of six months was the sentence allocated to those who had violated the 10th commandment’s injunction “not to covet one’s neighbours’ goods”, and a mere 28 days to those who had consistently failed to attend Sunday morning mass. (At my boarding school, it was not uncommon to hear an 11-year-old boast that he would only have to endure a few weeks in Purgatory now he had abandoned the night-time delights of self-abuse.)

Even though I currently regard this portrait of life after death as patently absurd, it did have one distinct advantage. It meant there were good reasons for constantly reflecting upon the lives of friends and relatives who had passed away. It gave one a licence for extended mourning. Cousins and aunts and grannies who otherwise might have long since passed out of one’s consciousness were regularly resuscitated by the need to pray for their eternal salvation.

In the secular world, once the dead are properly buried we can, nay, we should, forget about them. And there is no better way to seal up the coffin than the present predilection for memorial services. Everyone there can recite their favourite anecdote, pick out an apt bit of literary prose and sing along to the departed’s favourite pop song. “Thank God, that’s all over,” one mourner said to me last month as we were leaving one such service.

In my childhood religion, it was never all over. Not only did the dead need our regular prayers in order to escape purgatorial punishment but there would also be an opportunity to meet up with them on Judgement Day, and given a bit of luck (and, of course, divine approval) a chance to join them for eternity. A load of nonsense, but somehow so much more comforting than “Thank God, that’s all over”.

I recalled all the times I’d spent praying for the good fortune of the dead when I lost two of my closest and most valued friends. First to go, back in 2013, was my fellow sociologist and co-author Stan Cohen. For the best part of 25 years we had been in touch with each other on an almost daily basis. Not only had we been sociological collaborators but also partners in any number of anarchic escapades.

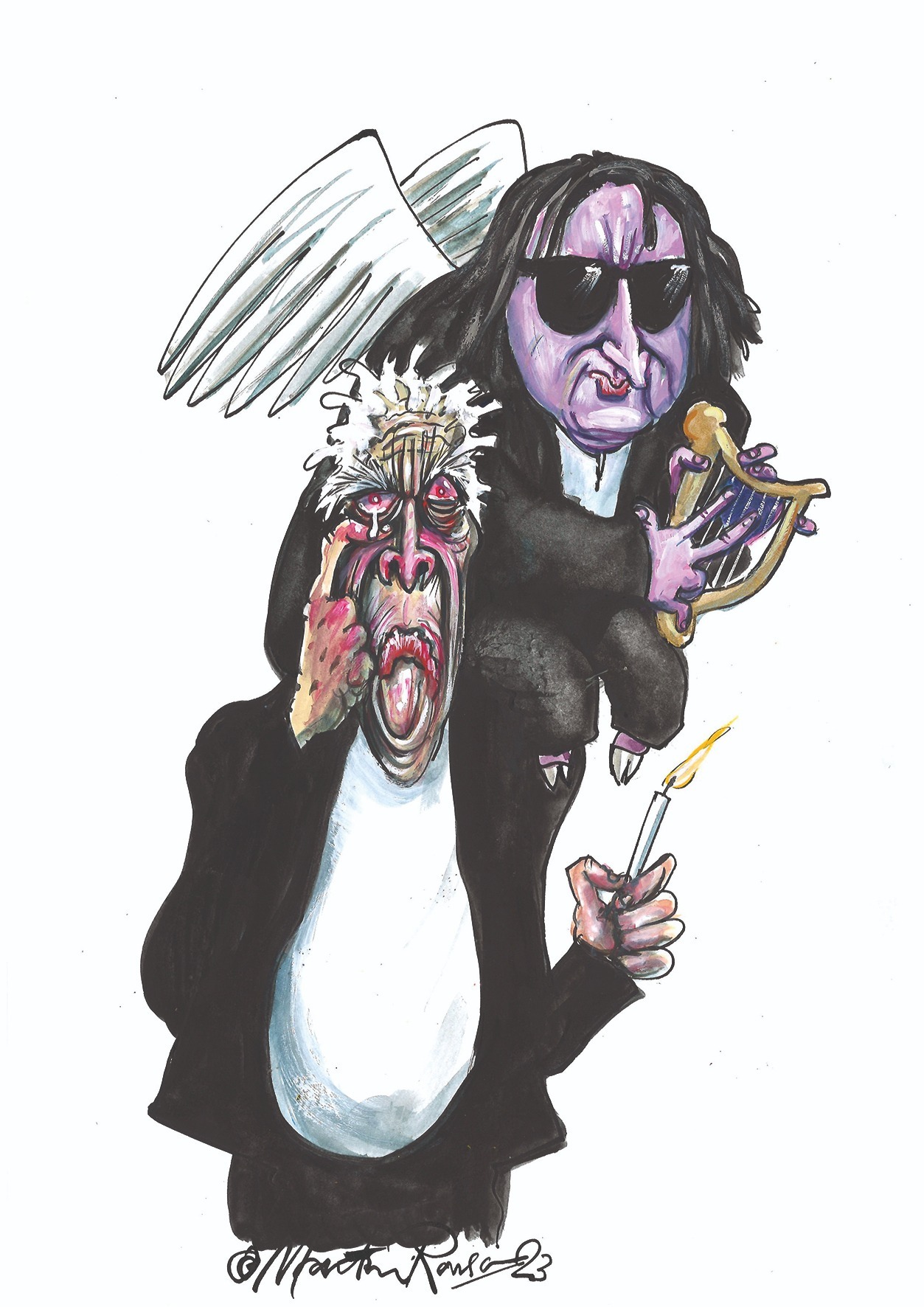

My second loss was equally profound. In December last year I learned of the death of Victor Lewis-Smith. I’d first come across this brilliant satirist and annihilator of all taken-for-granted truths when I was a naive sociology teacher and he was a music student at the University of York. We went on to make numerous radio and television programmes together, but what made Victor so special was his capacity for irreverent adventures. Only Victor could have spent one entire evening climbing to the top of York Minster from where he loudly issued a Koranic call to prayer before being removed from his ecclesiastical eminence by the local police.

None of this means that I have any wish to cling to a religious belief in my two friends having to endure a period in Purgatory before joining the angels and saints in everlasting bliss. But it does prompt the recurrent thought that atheism, while intellectually satisfying, is emotionally brutal when it applies its philosophy to the dead. It imposes a normative requirement upon the extent and nature of our mourning. It recommends nothing more than “getting on with it”. Frankly, it buries the dead too quickly.

This article is from New Humanist's autumn 2023 issue. Subscribe now.