The Prince and the Plunder (The History Press) by Andrew Heavens

In the autumn of 1867, a British-Indian army of 40,000 landed on the African shore of the Red Sea and began a long, winding ascent into the Ethiopian highlands. This huge force was assembled to retrieve 40 captives held by the first emperor of modern Ethiopia. Tewodros II was a charismatic leader. He was also, many historians have suggested, an unstable personality. When his diplomatic overtures to the European powers were refused he flipped, imprisoning the British consul. When the British stormed the fortress, Tewodros took a pistol and shot himself through the roof of the mouth.

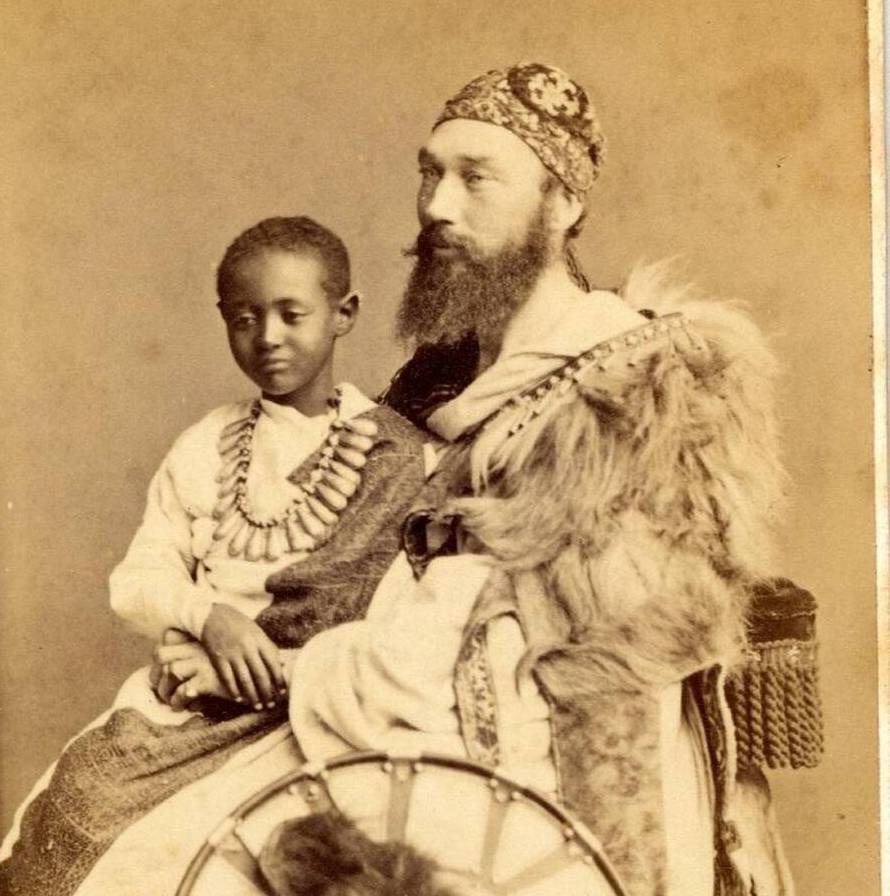

The first four chapters of Andrew Heavens’s new book recount the story of this remarkable expedition, but the focus is not on the campaign so much as its aftermath. Heavens is more interested in the ensuing plunder – the crowns and manuscripts and processional crosses that were looted and taken to Britain – and the tragic story of one young boy who was taken with them. This boy, the “prince” of the book’s title, is Alamayu. Heavens refers to him early on as the “hero” of the book, and he is a tragic hero indeed. Orphaned by the death of his mother, soon after that of his father, he was entrusted to the care of Tristram Speedy, a six-foot-six, flame-haired English adventurer who had endeared himself to Tewodros on an early mission to Ethiopia. We join the prince as he disembarks at Plymouth, the crowds gathering to stare at the son of the mad king, the tiny boy whose name “Alam-ayu” (meaning “I have seen the world”) would come to serve as a prophecy. In his first year in Britain, he was introduced to Queen Victoria, who wrote that “little Alamayou is a very pretty, slight, graceful boy of seven, with beautiful eyes and a nice nose and mouth, though the lips are slightly thick”; to Charles Darwin, who studied Alamayu’s facial expressions for his work The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals; and to Lord Tennyson, at whose house he was a regular guest.

When Speedy was assigned to a policing role in India, Alamayu followed, then on to Malaysia. Having been bounced around the furthest reaches of the empire, Alamayu was recalled to its core: the great public schools. The young prince found himself at Cheltenham, then Rugby and finally Sandhurst, each experience more alienating than the last. At the age of 19, Alamayu was found shivering in the outhouse of his lodgings in a fierce winter night. He contracted pneumonia – listed as the official cause of death – but contemporary sources also record that the young prince refused all food and medicine offered to him as a cure. Alamayu’s story, shorn of political intrigue and exotic ornamentation, is ultimately that of a lonely and scared boy who had no place in the world and no control over his own life. What is more, he knew it. It is visible in his eyes, in the pictures included by Heavens and poignantly commented on throughout the book.

But Alamayu’s story is only one part of Heaven’s book. The second theme, “the plunder”, is the one with most contemporary resonance. Hundreds of looted items from the Ethiopian expedition remain in British museums and private collections, a good portion of them not even on display. These items have long been the subject of repatriation claims, mirroring the better-known attempts of the Greek government to reclaim the Elgin Marbles, or Nigeria’s claims on the Benin Bronzes – claims only intensified by the recent revelations that over 2,000 items from the British Museum were found to be “missing, stolen or damaged”.

Heavens is keen to point out that there is nothing new in the moral objection to profiting from plunder – British Prime Minister William Gladstone raised objections to the practice in parliament over 150 years ago. Heavens’s own key argument for repatriation is that while these items matter little to British museum-goers, they matter a great deal to Ethiopians. Alamayu’s father is an icon in Ethiopia. In Addis Ababa and the Amhara region, the face of Tewodros is ubiquitous: emblazoned on T-shirts, posters, street art, the awnings of a thousand rickshaws. Britain cannot do right by Alamayu. But it is still possible to extend a hand of friendship by righting the historical injustice that estranged many thousands of treasures, and one small boy, from their home.

This article is from New Humanist's winter 2023 issue. Subscribe now.