Many adults can still name a favourite dinosaur. From the bunting-like triangles along the back of a stegosaurus, to the mace-like balled tail of the ankylosaurus, to the armour-plated horns and collar of a triceratops, there is something impossibly thrilling about their wildly ranging scale and fantastical features. My favourite, as a child, was the archaeopteryx, a giant flying reptile. Even the name was complex and mysterious. More than the painting of what the living creature might have looked like, it was the photographs of fossilised remains that captivated me: the contorted, impossible wingspan, seemingly trapped in rocks, like an insect in amber.

Some of that early fascination has stayed with me. During the Covid-19 lockdowns, I recall how much comfort I found in the number of unearthed discoveries, made as scientists and amateurs alike spent more time walking in quiet isolation, stumbling across potentially new species of fossils.

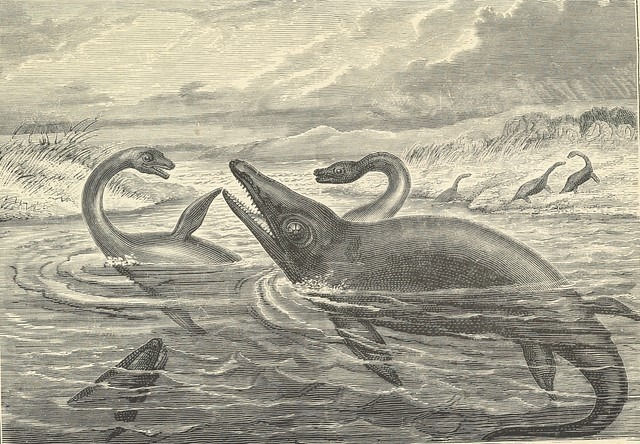

But it was in December that one of the most thrilling prehistoric finds of them all made international headlines. An almost complete skull of a 12-metre long pliosaur: a giant marine predator that lived at the time of the dinosaurs. This ferocious creature, with 130 giant curved teeth, emerged from the crumbling limestone cliffs of England’s famous Jurassic coast in Dorset. The skull alone was two metres long, drawing Sir David Attenborough to make a special documentary about the find.

The skull looked much as it would have in life: the ebony-dark teeth, pitted with long grooves, revealing the refined biology of a powerful carnivore. Even BBC News couldn’t resist describing the pliosaur as the “ultimate killing machine”. Perhaps that’s the key to our enduring obsession: a human attempt to make sense of the pure efficiency of something that seems to have emerged from our most terrible nightmares.

Our fascination with dinosaurs has deep roots, going back to the 19th century, when European and North American science elites tried to absorb the shattering implications of the fossils’ existence. How did these demon-like beasts fit with the Christian belief in God’s benign creation and the story of a Planet Earth that was less than 7,000 years old?

It both pleases and saddens me that the pliosaur was discovered in Dorset. Pleasing because it was here, in around 1811, that a young local girl – 12-year-old Mary Anning – together with her younger brother Joseph, discovered the first skull of another marine reptile, the ichthyosaurus. As one of the first such discoveries, it helped to transform our understanding of evolutionary theory. But Anning was mostly ignored and erased from accounts of early palaeontology. I was fortunate to be taught about her at school, more than 150 years later, when I was first falling in love with dinosaurs – yet even today she is hardly a household name.

It’s not surprising that Anning was written out of palaeontology by the men who went on to establish our national history museums. Victorian science, fascinated by dinosaurs, was also obsessed with pathologising the female condition. Women’s brains were smaller; their wombs might be damaged by too much intellectual stimulation. Even as discoveries enabled new understandings about the world, they were often used to reinforce old prejudices. Charles Darwin, while proposing his theory of evolution, was also among the respected thinkers of the time who promoted the idea of inferior races. Perhaps it’s appropriate that the word “dinosaur” has become a derogatory label for people (usually men) deemed to hold outdated views.

But there is another gripping element to the story of the Dorset Pliosaur. Part of the drama was the “race against time” to rescue the skeleton before the cliff crumbled. Climate-change-accelerated coastal erosion has brought more and more of these lost beasts to the surface. I think again of why dinosaurs enthrall us. Surely it is also because of the vastly contradictory timescale of how long they thrived (180 million years), only to be suddenly wiped out in the aftermath of an asteroid impact, according to the widely accepted Alvarez extinction theory.

Victorian writers Edgar Rice Burroughs and Arthur Conan Doyle imagined the nightmare of bringing them back to life; a fear still evident today in the Jurassic Park film franchise. But the real nightmare lurking in dinosaur fossils is the brutal totality of their extinction. Not a symbol of a lost past, but of a possible human future.

This article is a preview from New Humanist's spring 2024 issue. Subscribe now.