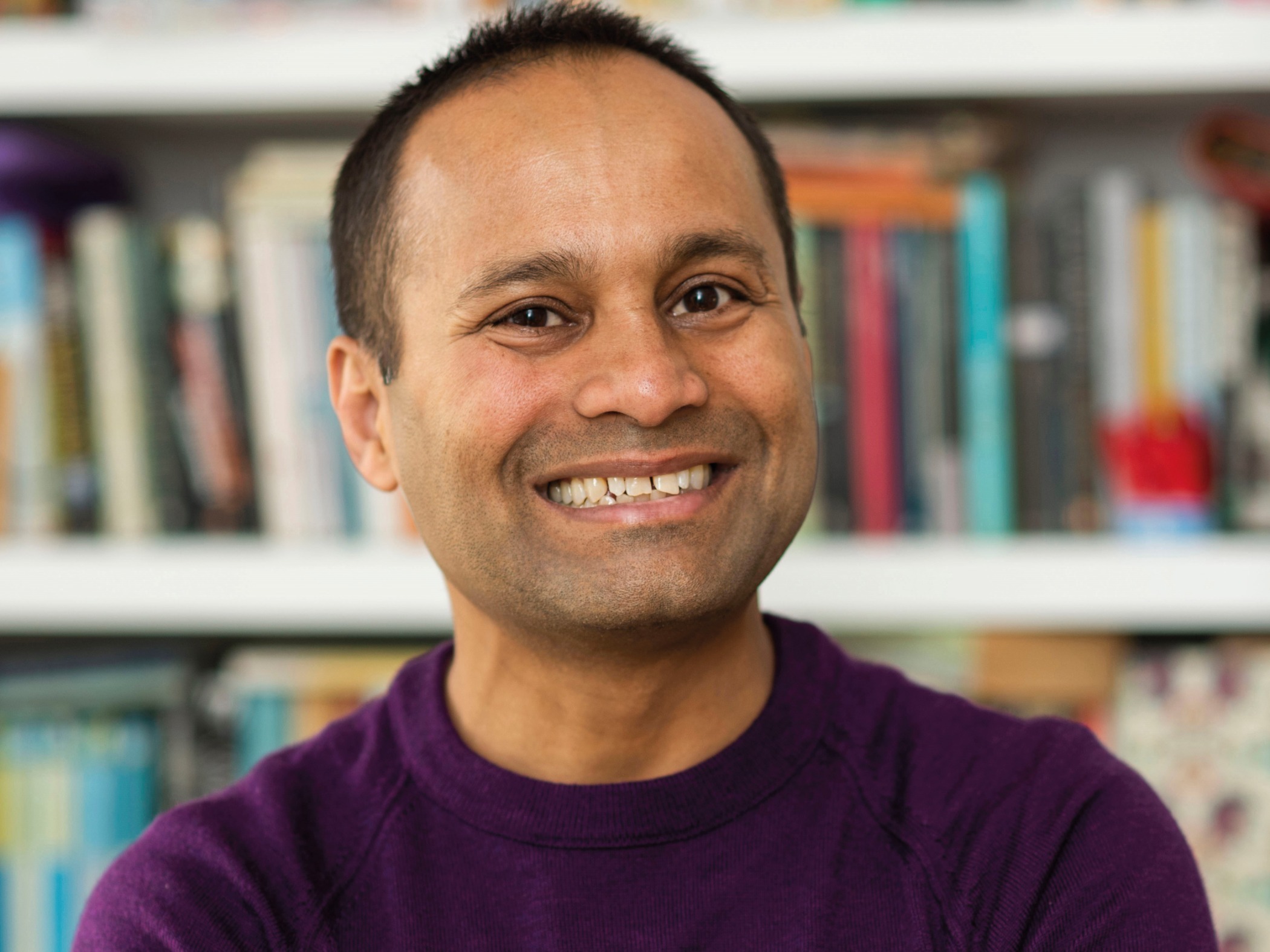

"I’ve done quite a lot of work in various media, from making videos, to writing live science shows, to writing books,” Alom Shaha tells me, over the phone from his home in Kent. “And I would put it all down to the fact that I kind of fucked up my physics degree.”

There are direct routes from studying physics to a career in teaching physics. Shaha took the long way around.

Born in Bangladesh in the early 1970s, Shaha moved to south London as a child. In The Young Atheist’s Handbook (Biteback, 2012), he describes a troubled home life: his father was cruel and violent; his mother suffered badly from mental illness and died, from complications arising from pregnancy, when Shaha was 13. School was an escape.

“My home wasn’t a happy place,” he tells me now. “Getting on the 176 bus every morning was like stepping through the wardrobe ... I grew up on a housing estate in Elephant and Castle, and then every day I would go to this private school full of kids from a different world, literally: much richer, almost entirely white. Nothing like the community I’d grown up in. It was very much like one of those classic children’s stories, you know, the kind of Harry Potter thing, escaping home to go into a different universe.”

Shaha – who had qualified for a free place at the school – excelled academically, particularly in English. But it was in science that he saw a glimpse of his future.

“From about 14, I had these amazing physics and chemistry teachers,” he says. “Part of what they were doing in their lessons was training people to become scientists. And that was a fundamental difference: the idea that science was something that any of us could go on to do, and therefore that that was just part and parcel of what was kind of ‘in the ether’ of the lessons. Whereas English literature was definitely this kind of holy thing, and all we could do was worship at its altar. At no point in my education was I ever given the impression by my teachers that writing was something someone like me could do for a living.”

But after scraping through a disastrous first year at university – “I got 11 per cent in my astronomy exam” – and graduating from UCL with a 2:2 in physics, he felt lost. He waited tables, volunteered at homeless shelters and spent a stint as an unpaid intern for the Liberal Democrat MP Simon Hughes, before another turning point came along.

“After graduating, I’d gone off to work at a camp for homeless and disadvantaged kids in upstate New York. Really, I was just running away from home. I wanted to get as far away from everything as possible. And I had this wondrous three months in the American countryside where I was dealing with children who were far more disadvantaged than me – really, from some horrific backgrounds. When I got there, they said, ‘You, you’ve got a physics degree, right? You’ll be teaching science.’ I remember just standing in front of the kids and it felt kind of natural to me.”

It was an experience that came back to him when the idea of training as a teacher came up. “I don’t want to claim noble intentions,” he laughs, admitting that a guaranteed salary was the prime motivation. But he soon found that teaching offered him far more than a wage.

“What I found was that just being in the classroom kind of restored me psychically. It just made me remember the fact that I had loved school, that school was a place where I had flourished and I had always been happy.

“And I, you know, I think it helped me to climb out of a depression that I’d been in for a number of years – because I rediscovered how to be the person that I like to be.”

Jump-cut to the present and a recent book, Why Don’t Things Fall Up? (Hodder & Stoughton, 2023) which aims to fill in the gaps in the science we all learned – or were supposed to learn – at school. Why does ice-cream melt? What is the smallest thing? What are stars? What am I made of? It’s clearly a book written by someone who not only knows and understands science but also wants other people to – not just to love science, to marvel at it, but to understand it. In other words, it’s a book written by a born teacher.

“The book doesn’t really do anything that I don’t do in the classroom,” Shaha says. “That was one of the things that I really wanted to convey: everything in the book is what you and every other student should have got in class. Because otherwise you’ve not been taught science properly. You know, you have to start off with ‘what is science?’ And I think actually that’s missing from a lot of science education.

“One of the things that really helped me get my head around science was understanding at an early age, thanks to those teachers I had, that what we’re dealing with is scientific models, and that what science does is help us to understand the world in terms of things we’re already familiar with. The more you understand, the more you can understand.”

I mention theoretical physicist and teacher Richard Feynman, and his dictum that if he couldn’t teach it to freshman students, then he didn’t really understand it. Shaha seizes enthusiastically on the reference.

“Here’s why people should admire Feynman, not because he was a brilliant teacher, but because, like any good teacher, he wanted to know if his teaching was any good, actually any good – [to know] whether or not his students actually learned anything.

“That’s the thing with teaching, you see. Which makes it rather different to science communication. You know, I can give a talk to an audience of hundreds at the Cheltenham Science Festival and they can all clap and cheer and go away feeling good about themselves. But you know, nobody will ever check to see whether they’ve understood anything.

“I think part of the problem with science communication is that it flatters the audience. I think people want to read stuff or listen to stuff that makes them feel like they’ve understood something. That’s not what teachers have to do. We can’t just inspire the kids and make them go away with the feeling that they’ve learned something. They actually have to learn things.”

When The Young Atheist’s Handbook came out in 2012, “sci-com” was still riding a wave of popularity, fronted on television by the likes of Brian Cox and Dara Ó Briain and represented in the bookshops by Ben Goldacre, Simon Singh, Richard Dawkins and many others. Campaigners sought to have Mark Henderson’s The Geek Manifesto sent out to every MP in Parliament. There was a fleeting feeling that science literacy could save the world. I ask Shaha how he feels about that now.

“I think if everybody understood science or ‘got’ science or believed in science, to the same extent that I do, maybe we would have fewer vaccine conspiracists and perhaps we would have everybody caring about trying to sort out climate change,” he says. “But it’s not as simple as that. The people in power, the people running big corporations, people running governments, I think they’re perfectly capable of grasping the science of climate change. And they’re still not doing anything about it.”

Shaha is a dad to two young daughters. I ask him how he would characterise their relationship with science. “For me, for my kids, science isn’t going to be this other weird thing that only geeks do or whatever. It’s just part of their everyday experience of cultural activity. It’s something people do, it’s something humans do. After we’ve finished eating and pooing and all that, you know, humans do things like reading and writing and listening to music – and science.”

A few years ago, Shaha took on the Wonka-like persona of “Mr Shaha” in two vibrant and hugely original children’s books on science and engineering, Mr Shaha’s Recipes for Wonder and Mr Shaha’s Marvellous Machines (published by Scribble, in 2021 and 2023 respectively).

“That came out of my parenting and teaching,” he says. “The Mr Shaha books are my particular take on the classic science children’s book. But one of the things I felt was missing from a lot of children’s science activity books was what science was actually about.

“I tried to write a book that would help parents to become their children’s first science teacher. It’s very clear to me that all parents are their kids’ first teachers: most parents will teach their kids to count, most parents will teach their kids their first letters, most parents will teach their kids to sing ... and yet when it comes to science, an awful lot of parents would lack the confidence to even broach the subject. That’s where the Mr Shaha books come from: the idea that parents can and should introduce their children to scientific thinking.”

Another children’s book – How to Find a Rainbow, with illustrations by Sarthak Sinha – was published in February by Scribble. The story, which covers how rainbows are formed, also includes a guide on how children can make one of their own, bringing the science in the story to life.

“It’s the book I’m most excited about ever, because I wrote it for my children,” Shaha says. “If you read a lot of picture books, you’ll know they often have some kind of message or moral at the end – you know, ‘be kind’ or whatever. And I wanted to write a book where there’s a bit of science at the end instead.”

Teaching, rather than preaching. For this atheist-humanist-writer-teacher-dad, it seems rather apt.

This article is from New Humanist's spring 2024 issue. Subscribe now.