Laugh? I nearly cried. This memoir by the approaching-seventy playwright Simon Gray comes adorned with promises of hilarity. Upon closer reading, the compliments from the likes of Barry Humphries and Lynn Barber all seem to apply to Gray's earlier book, The Smoking Diaries. Doubtless, smoking is absurd, to those who persist in doing it and those who stand near them. So, too, is pet ownership, a major theme in The Year of the Jouncer.

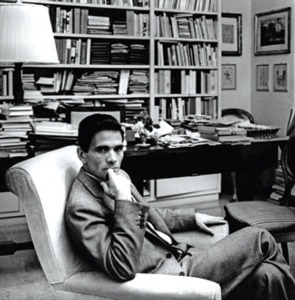

But what Gray delivers this time, with wit, to be sure, is a bleak picture of a life drawing to a close. Why did he spend so much of his time dramatising the human predicament? The playwright whose dramas include Butley, Otherwise Engaged and The Old Masters looks back at himself toying with characters who wonder what they are doing here and why. He decides that it is time to look at himself, to stop avoiding the subjects of death and dying and to face the figures on his heart, bladder and bowels that his doctor faxes through to him with asterisks to mark the statistics to worry about.

What he sees when he looks in the mirror is a 68 year ex-alcoholic man with the "paunchy slackness, of low self-esteem, comfortably lived with". He portrays himself also as happily married, an ex-alcoholic comfortable with his appetites which include consuming vast quantities of Diet Coke and Green & Black's organic white chocolate. He jumps about through old memories, such as that of a Westminster school friend who saw death coming and died young.

Revisiting Canada where he spent the war years, he gets a whiff of things past when he sees a party of schoolchildren of a sort not seen in England: shrieking joyfully with not a swear word to be heard. His mind is flooded with scenes from old movies. Why does Cary Grant's face so stick in his mind? But was Gary Cooper's handsomer?

Gray faces the searing question of the aging: what is the use of remembering the past? To avoid becoming a zombie, he suggests. "The quickest and most successful way of eliminating the past is to eliminate the memory." Thus seen, there need be no terror of death, only of Alzheimer's. He vows to continue telling himself, as his close friends die off, "At your heart, you are a merry man".

The son of a McGill-trained Canadian doctor, Gray spent his early years at Hayling Island in Hampshire. He was told as a baby he had jounced his pram down the path and became 'the jouncer' from then on. His family moved to London and settled in Oakley Gardens in Chelsea. It was not an idyllic childhood: his father, medically convinced that a child should sleep on its back, tied a hairbrush to the front of little Simon's pajamas in an unsuccessful attempt to thwart the infant's natural inclination.

Memories of Mummy are nicer. Gray's descriptive gift beautifully describes an afternoon at The Oval where she took her boys to learn how to be gentlemen: "'Well played, jolly well played!' from Mummy, sitting on the grass behind the boundary, near the pavilion, dressed for the occasion in a floral summer frock, a large summer hat on her head, legs tucked athletically under her, a hamper containing boiled eggs, unwieldy chunks of bread and marge, and a Thermos of sweet tea at her side."

The idyllic picture also contains disturbing elements of cigarette smoke and red lipstick that suggest another life. Perhaps, ruminates the playwright, it was Johnny, the lover he gave her in his play The Late Middle Classes, written when he was older than she was when she died: "a paternal gift, you might say, from her aging son to the ghost of his still-young mother".

Thoughts of death cause Gray to open his book with a memory of the death of the actor Alan Bates, a wonderful performer of Gray's work, who died on Boxing Day in 2003, and he spends much of his charmingly jerky text inserting fragments of Bates. And is it name-dropping to frame his life-story with scenes from his friendship with Harold Pinter and Lady Antonia Fraser?

Jouncer was obviously written before Pinter was sanctified with a Nobel Prize, and the two men, as playwrights, Holland Park neighbours and holiday companions in Barbados, share perspectives on the theatre, the 20th century and the weather. The memoir closes with a clear snapshot of the author looking down from his balcony in Barbados at Harold and his wife playing bridge, her "face partly obscured by one of her majestic hats" and him making "an emphatic putting-down-a-card-take-that! kind of movement".

If you observe life in detail like that, perhaps play-writing comes easy.