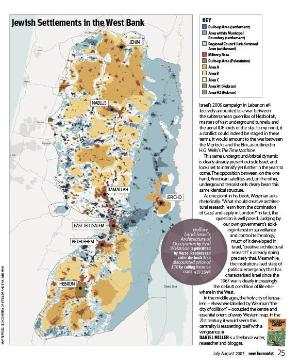

Look at the map produced by architect Eyal Weizman for the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem (a high-res PDF of this is available here). Plotting the Jewish settlements in the West Bank (blue) against the built-up Palestinian areas (brown), the map transposes these with the original terms of the Oslo Accord (light brown, yellow) to reveal a total territorial incongruity.

We owe the reproduction of this map to Eyal Weizman, who colaborated with B’Tselem on the detailed research which underpins it and has now included it in his new book Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation. This latter work amounts to the freshest and most eye-opening analysis of the Israeli occupation of Palestine to have been produced for some time. The power of insight which this work achieves, its focus on the material and literally concrete reality of occupation, is frankly astonishing.

Weizman, who combines work as an architect, campaigner and founding director of the Research Architecture programme at Goldsmith’s College in London, ranges widely, combining historical, political and architectural inquiry into the form of domination. He shows how an obscure 1918 Jerusalem bylaw regulating building materials was extended into the occupied territories in order to create the impression that these new settlements were an integral part of the Old City. He combines this with a detailed journalistic investigation into the surprising operational interest in post-structuralist philosophy taken by the Israel Defence Forces (in which he served). Yet another focus shows how the assassination squads of the Shin Bet have become bureaucratically entrenched to a point where assassinations are now considered simply another method of exerting political influence.

According to Weizman, the work “form[s] an ‘archival probe’ investigating the history and modus operandi of the various spatial mechanisms that have sustained – and continue to sustain – the occupation’s regime and practices of control . . . Cladding and roofing details, stone quarries, street and highway illumination schemes, the ambiguous architecture of housing, the form of settlements, the construction of fortifications and means of enclosure, the spatial mechanisms of circulation control and flow management, mapping techniques and methods of observations, legal tactics for land annexations, the physical organisation of crisis and disaster zones, highly developed weapons technologies and complex theories of military manoeuvres – all are invariably . . . indexes for the political rationalities, institutional conflicts and range of expertise that formed them.”

Underpinning this approach is a genuine political seriousness. “Despite the complexity of the legal, territorial and built realities that sustain the occupation, the conflict over Palestine has been a relatively straightforward process of colonisation, dispossession, resistance and suppression,” Weizman writes, before going on to draw particular attention to the effective Israeli expropriation of West Bank water reserves (Israel uses 83 per cent, the Palestinians the remaining 17 per cent), land resources (according to presently enforced Ottoman Land Law of 1858, any piece of land that Palestinians cannot prove is privately owned legally reverts to Israel qua Sovereign) and labour (according to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, Israeli Arabs earn approximately 60 per cent of the yearly wage of Jews).

On the vexed current question of apartheid, meanwhile, Weizman is scathing. “[The Wall] has become particularly associated with the word ‘apartheid’, although even at the height of its barbarity, the South African regime never erected such a barrier.” That US soldiers are currently constructing a wall in Baghdad to separate Shia and Sunni areas merely confirms the ominous globalisation of these military/architectural practices.

This by no means exhausts Weizman’s fascination with spatial analogies. In the final chapter of Hollow Land, he suggests that Israel’s 2006 campaign in Lebanon effectively amounted to a war between the subterranean guerrillas of Hezbollah, masters of vast underground tunnels, and the aerial IDF, lords of the sky. To my mind, if a conflict could indeed be staged in these terms, it would amount to the war between the Morlocks and the Eloi, as outlined in H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine.

This same underground/orbital dynamic is clearly already present outside Israel, and looks set to intensify yet further in the years to come. The opposition between, on the one hand, American satellites and, on the other, underground terrorist cells clearly bears this same identical structure.

At one point in his book, Weizman asks rhetorically: “What should creative architectural research ‘learn from the domination of Gaza’ and apply in London?” In fact, the question is well posed. Judging by our own government’s abiding interest in surveillance and control technology, much of it developed in Israel, “creative architectural research” is already doing precisely that. Meanwhile, the institutionalised state of political emergency that has characterised Israel since the 1967 war is clearly increasingly the default condition of life elsewhere in the West.

In the middle ages, the holy city of Jerusalem – elsewhere labelled by Weizman “the city of collision” – occupied the centre and essential orient of every Western map. In the 21st century, it would seem this centrality is reasserting itself with a vengeance. ■

Daniel Miller is a freelance writer, researcher and blogger.