You must change your life by Peter Sloterdijk (Polity Press)

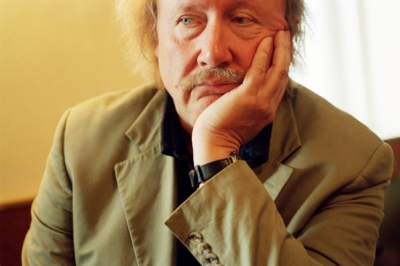

Peter Sloterdijk does not conform to the stereotype of a German professor of philosophy. His prose may be stodgy and long-winded, but he can also be funny and unconventional, and no one could accuse him of being predictable. He first came to public attention in the early 1980s, with an exuberant Critique of Cynical Reason in which he attacked the dreary pieties of know-it-all neo-Marxist theorising, and argued that the true cynic is the one who knows how to laugh rather than merely to sneer. Since then he has kept himself conscientiously at the margin of conventional academic life, while making a living as a broadcaster and TV presenter, and a prolific best-selling author and journalist.

Sloterdijk’s attacks on leftism have always been more neo-radical than neo-conservative, but he does not seem to mind if people get him wrong. He takes pleasure in teasing the many-headed demons that still haunt the German national psyche, and has never shrunk from presenting himself as a disciple of Nietzsche and Heidegger, who, in Germany at least, seem incapable of shaking off the taint of Nazism. A decade ago, Sloterdijk published a pamphlet called Rules for the Human Zoo, in which he argued that traditional methods of securing a future for humanity were losing their power. He claimed that we were moving from an epoch of careful reading to an epoch of careful breeding, or, as he put it, from Lektion to Selektion.

You might think that this was a fair comment on an age where machines can read our DNA more readily than many of us will read a book; but anything that sounds like eugenics is taboo in Germany, and if there can be such a thing as a wicked word, then Selektion – remembered for its use in Nazi death camps – is as guilty as hell. At the high court of German public opinion, Sloterdijk was condemned as either a crypto-Nazi or an infantile attention-seeker, and in any case an exponent of the most shocking bad taste: the Lady Gaga of philosophy.

But Sloterdijk is both seriously learned and brilliantly creative, and he has a talent for wit, if not brevity. He no longer speaks so freely of selective breeding, but in his mountainous new book, translated as You Must Change Your Life, he takes up his old theme under the heading of anthropotechnics, meaning the project of treating human nature as an object of deliberate manipulation. The term originated in the early euphoria of the Russian revolution, but as far as Sloterdijk is concerned it refers not just to modern biological eugenics, but to techniques of individual and collective self-transformation that date back several thousand years, to the earliest beginnings of any kind of social existence that we would recognise as resembling our own. Sloterdijk follows Michel Foucault in seeing human life not in terms of a struggle between those who wield power and those who are subject to it (he dismisses this version of history as leftist kitsch), but in terms of the networks of “discipline” through which we live our lives and construct our world. Human beings are self-forming animals, he says, and the history of human society is the history of anthropotechnics.

Rather like his intellectual role-models – Nietzsche, Heidegger and Foucault – Sloterdijk sets himself the task of challenging the stories we like to tell ourselves about how the obfuscations of the past have at last given way to our own self-evident good sense. In particular he wants to overthrow the popular myth of enlightenment humanism: the idea that, in or around the 18th century, philosophers realised that the old ideas of God were no more than projections of human dreams, and thus restored humanity to its proper place at the centre of the cosmos. For Sloterdijk, the very idea of religion is a myth, and so is the humanist idea of humanity: both of them depend on an over-valuation of metaphysical opinions (about such topics as God, truth and the soul) and a refusal to face up to the fundamental fact of human existence, namely that all of us are condemned to lead a “practising life”, in an interminable labour of self-fashioning.

Rather like his intellectual role-models – Nietzsche, Heidegger and Foucault – Sloterdijk sets himself the task of challenging the stories we like to tell ourselves about how the obfuscations of the past have at last given way to our own self-evident good sense. In particular he wants to overthrow the popular myth of enlightenment humanism: the idea that, in or around the 18th century, philosophers realised that the old ideas of God were no more than projections of human dreams, and thus restored humanity to its proper place at the centre of the cosmos. For Sloterdijk, the very idea of religion is a myth, and so is the humanist idea of humanity: both of them depend on an over-valuation of metaphysical opinions (about such topics as God, truth and the soul) and a refusal to face up to the fundamental fact of human existence, namely that all of us are condemned to lead a “practising life”, in an interminable labour of self-fashioning.

The practising life always involves an attempt to break away from the flatlands of inherited habit, and a yearning for what Sloterdijk calls “verticality” – a desire to climb the highest moral mountain peak, or to dance with effortless abandon on the high wire of ethical perfection. At root, the practising life is essentially “ascetic”, but asceticism can take two very different forms: not only the despicable floor-gymnastics of those who have lost their nerve – servile, resentful, moralistic sub-humans of the kind lampooned by Nietzsche – but also the dramatic self-elevation of the classical super-hero. After two or three thousand years, the old ascetic world gave way to the modern one, but the transition had nothing to do with old sociological chestnuts about secularisation: it was about the rise of the modern state, which, with its overweening interest in the health and education of its citizens, required the focus of asceticism to shift from reform of the individual to the “mass rebuilding of the human condition”.

By the end of the 19th century, however, the light of asceticism was beginning to fade, and the practising life began to lose its old spiritual content. This process of “de-spiritualisation” proceeded in two different directions, one political, the other athletic. Vladimir Ilyich Lenin created the October Revolution in order to allow his followers to dissolve their bad old selves in the unspeakable ecstasy of communist revolution; and his contemporary Pierre de Coubertin created the Olympic Games to allow his followers to lose themselves in the struggle to become the greatest athletes in history of the world. In the wake of these parallel movements, Sloterdijk identifies a valiant uprising of “cripples” (Krüppel, as he insists on calling them), with a virtuosic digression about the 20th-century ascetic Carl Unthan, a plucky musician born without arms, who achieved celebrity by playing the violin, very beautifully, with his feet.

I am sure I have not grasped all the ins and outs of Sloterdijk’s global history of anthropotechnics, despite my best efforts; and I suspect that his copious prose was sometimes too much for Wieland Hoban, his gifted translator. But if Sloterdijk sometimes nods and slips, he never flags, and he certainly deserves some shelf-space alongside Nietzsche, Heidegger and Foucault. Like them, he reminds us that our fond notions of our place in history are not necessarily true: that alternatives are always available, and that what seems perfectly obvious to us may well turn out to be false.