In Britain we seem to be increasingly fond of celebrating anniversaries. This year, of course, the theme is slavery: Wilberforce hagiography is everywhere, the Royal Mail and Royal Mint have produced stamps and coins for the occasion, and there are concerts, plays and exhibitions up and down the country.

Last year, 350 years of Jewish life in Britain – not an especially significant number – were marked by a similar plethora of events. In June, Tony Blair attended a commemorative service at Bevis Marks, the oldest synagogue in Britain; in September, the Greater London Authority organised a festival of Jewish life in Trafalgar Square; and exhibitions were hosted by the House of Commons and the National Portrait Gallery.

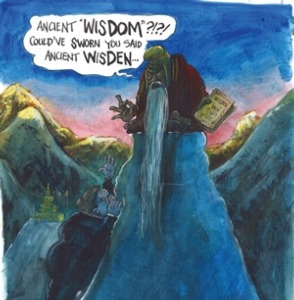

On the face of it, greater mainstream recognition of milestones in minority history appears to be a positive development. But in the slide from commemoration to celebration one thing tends to be forgotten: the historical record. Although the Home Office’s official bicentennial booklet acknowledges that slavery continued in parts of the empire for 30 years after 1807, in reality it persisted well into the 20th century – in Sierra Leone as late as 1928. In the case of the 350th anniversary of Anglo-Jewry, it’s widely believed that Oliver Cromwell readmitted the Jews to England in 1656, after they had been expelled by Edward I at the end of the 13th century. Cromwell’s act is thought to have brought about a shift in English attitudes from mediaeval anti-semitism to modern philosemitism; on Radio 4’s “Thought for the Day” the Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks referred to the readmission as “one of the great reversals of all time”.

But Cromwell did not readmit the Jews to England in 1656. Despite the 13th-century expulsion, Jews were never entirely absent from England, and a number of prominent Jewish merchants arrived during the 16th century; by the middle of the 17th there were about 200 Jews living here. Many had converted to Christianity, but some practised their religion in secret. In 1655 Menasseh ben Israel, a leader of the Jewish community in Amsterdam, came to England on a mission to persuade Cromwell to let the Jews back in. In December of that year, a conference of merchants, lawyers and theologians met in Whitehall to discuss the proposal.

After many days of heated debate, however, the Whitehall conference failed to reach a verdict. A community of Jews was gradually established in England in the second half of the 17th century, but there was no decisive act of readmission. Furthermore, only a few hundred or so arrived in comparison to the over 50,000 Huguenot immigrants of the same period. In the following centuries, the Jews’ status and livelihoods were repeatedly threatened, and they continued to be classed as aliens.

The readmission story only became “fact” in the 19th century, when the large-scale immigration of Eastern European Jews to Britain prompted a rise in anti-semitism and xenophobia. Increasingly anxious about their position within British society, the Anglo-Jewish community seized on the comforting precedent of 1656 in order to reassure their hosts that the Bolshevik masses gathering in the East End of London would not rock the boat; the first “Resettlement Day” was held in 1894.

The Victorian celebration of readmission was the result of a broader development, too: the growth of the idea that Britain was a uniquely tolerant country. In the midst of Empire and the Puritan revival, Victorian commentators resurrected the nonconformist pioneers of the English Civil War as the fathers of religious tolerance. Today, in the wake of the supposed failure of the multiculturalist “experiment”, British political leaders are returning to this Victorian idea in order to tackle the religious disharmony which, if anything, seems to be getting worse. It cropped up in Culture Minister David Lammy’s bicentenary speech in March: “We need to explain to the young why tolerance, why freedom and why human rights are so important, and how we arrived at this place today.”

And this teleological rationale fits with the government’s broader efforts to claim tolerance as a “core” British value: in January last year, Chancellor Gordon Brown made his pitch for the union flag as a “British symbol of unity, tolerance and inclusion”. If the trumpeting of tolerance in the 19th century was prompted by immigration anxiety, in the 21st it is unease about Islam that is prompting the conflation of description and prescription.

In a speech in Downing Street last December, Tony Blair made the following beautifully paradoxical statement: “Our tolerance is part of what makes Britain, Britain. So conform to it; or don’t come here. We don’t want the hate-mongers, whatever their race, religion or creed.”

The repeated assertion of British tolerance will not solve the problem of religious and ethnic disintegration, because rather than being neutral, tolerance is subtly coded as a native, Christian quality: a kind of benign yet coercive ecumenicism.

As long as church and state remain intertwined, non-Christians are accommodated on a de facto rather than a structural basis, and the egalitarian principle is performed through cultural and institutional displays of diversity. In lieu of warts-and-all history and a genuine recognition of difference, the anniversary show looks likely to run and run. ■

Eliane Glaser’s book Judaism Without Jews is published by Palgrave.