When David Hume lay dying in his Edinburgh bed in November 1776, he asked his doctor not to hide the terminal nature of his condition from his friend, Colonel Edmondstone. “Doctor,” he said, “as I believe you would not choose to tell any thing but the truth, you had better tell him, that I am dying as fast as my enemies, if I have any, could wish, and as easily and cheerfully as my best friends could desire.”

In death, as in life, Hume was a model humanist. He combined an unblinking realism about the human condition with a pragmatic desire to make the most of the little life we have.

His deathbed reading, for example, was not exactly escapism: it was Lucian’s Dialogues of the Dead. Reflecting on it, he concluded that he would not be able to offer Charon any reason why the time was not right to cross the Styx to Hades. “I have done every thing of consequence which I ever meant to do,” he said, “and I could at no time expect to leave my relations and friends in a better situation than that in which I am now likely to leave them. I therefore have all reason to die contented.”

Of all the possible excuses he might nonetheless have offered, one, he believed, was particularly useless. “I have been endeavouring to open the eyes of the public,” he imagined pleading to Charon. “If I live a few years longer, I may have the satisfaction of seeing the downfall of some of the prevailing systems of superstition.”

“That will not happen these many hundred years,” he imagined Charon replying. “Do you fancy I will grant you a lease for so long a term? Get into the boat this instant, you lazy loitering rogue.”

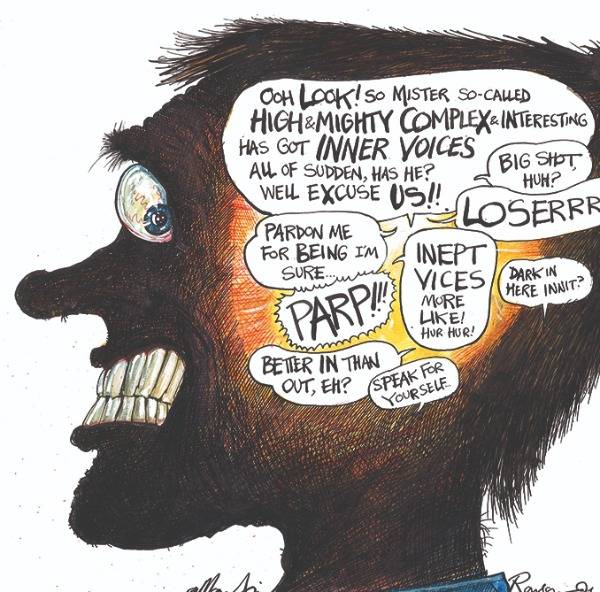

Yet modern-day humanists do not always display the same subtlety and modesty as their enlightenment hero, particularly when it comes to reason and religion. Modern defenders of rationality and science against the threats of irrationality and superstition clearly have Hume on their side. But Hume was never as gung-ho about the power of reason as many rationalists are today. On the contrary, he believed that the kind of empirical reasoning we rely upon rests on principles of cause and effect that can neither be proved logically nor discovered experimentally. Reason is the best means we have for discovering truth, but it is a very imperfect tool. Hence Hume encourages a kind of humility which is the exact opposite of the hubris which atheist rationalists are often accused of displaying, with some justification.

For Hume, uncertainty is not something that can always be defeated by reason, but it can be tamed by practice. Hume’s cure for his insoluble sceptical doubts was to play billiards, where the reality of cause and effect cannot be doubted. This was a living demonstration of his advice that one should “be a philosopher; but, amidst all your philosophy, be a man.”

Hume’s moderation is also revealed in his thoughts on religion. It has become commonplace today to describe Hume as an atheist who declared a more moderate agnosticism only to avoid the wrath of the still-powerful churches. But the reasons for thinking this are somewhat dubious, born not of evidence but the desire to have Hume on our team.

For example, it is often said that Hume’s arguments clearly lead us to atheism, so his refusal to say so explicitly can only be a kind of politically astute coyness. But Hume’s arguments do not necessarily lead to atheism; they lead to the conclusion that there are no compelling rational reasons to believe in God, nor is there any evidence that God exists. However, the hypothesis of God cannot be shown to be an incoherent or false one.

This leads to an agnosticism that is certainly very close to atheism, since it suggests that we have no good reason to believe in God, even if we can’t rule out the possibility that he might exist. This is pretty much the basis for what I call “defeasible atheism”, which holds that any uncertainty over God’s non-existence does not require that we remain entirely neutral on the matter and sit on the agnostic fence.

But Hume may well have resisted the atheist label for reasons of intellectual integrity. Because he was very comfortable with uncertainty, he would have seen no reason to express more certainty than was strictly necessary. In the case of God, we are not compelled to reach any firm conclusions about his existence or non-existence. Because it is enough to carry on as though God does not exist, it is simply going too far to assert that he actually does not.

This may seem like hair-splitting, and I for one think that to advocate agnosticism suggests the question of God’s existence is much more finely balanced than it is. But Hume nonetheless provides an important reminder that seeking to persuade others God definitely does not exist is too tall an order, and unnecessary. Hume’s achievement was not to kill God, but to make him irrelevant. Modern-day humanists should remember that deicide is not the most effective or rational way to build a society without religion.

Julian Baggini is editor of The Philosopher’s Magazine