I’m not at all anxious to take part in the absurd game of New Year resolutions but I have decided, with all the new-found passion of a man who has otherwise spent the rest of his life turning indecision and lack of commitment into an art form, that this will be the year when I finally come to terms with my friends.

Instead of simply assuming that Martin and John and Celia and Gordon are my close buddies I am going to tell each of them on the very next occasion that we meet that they hold a very special place in my affections. I haven’t yet worked out the precise form of words but I shall probably wait until after the third or fourth drink and then remind them that we have been hanging around together for the best part of twenty years and suggest that the time has at last arrived when we should explicitly admit – and here I’ll lean forward and fix them with my most affectionate smile – that we are the best of friends.

What has prompted this move is an article by a sociologist of friendship who points out that although we now live in an age in which we choose our regular companions rather than being forced to simulate affection for blood relatives with whom we feel little or no affinity, very few of us, if we were asked to name our best friends, have any idea whether the feeling might be mutual. Quite unlike some of the exotic tribes he goes on to instance, we even lack special names for our first and second and third best friends.

What has prompted this move is an article by a sociologist of friendship who points out that although we now live in an age in which we choose our regular companions rather than being forced to simulate affection for blood relatives with whom we feel little or no affinity, very few of us, if we were asked to name our best friends, have any idea whether the feeling might be mutual. Quite unlike some of the exotic tribes he goes on to instance, we even lack special names for our first and second and third best friends.

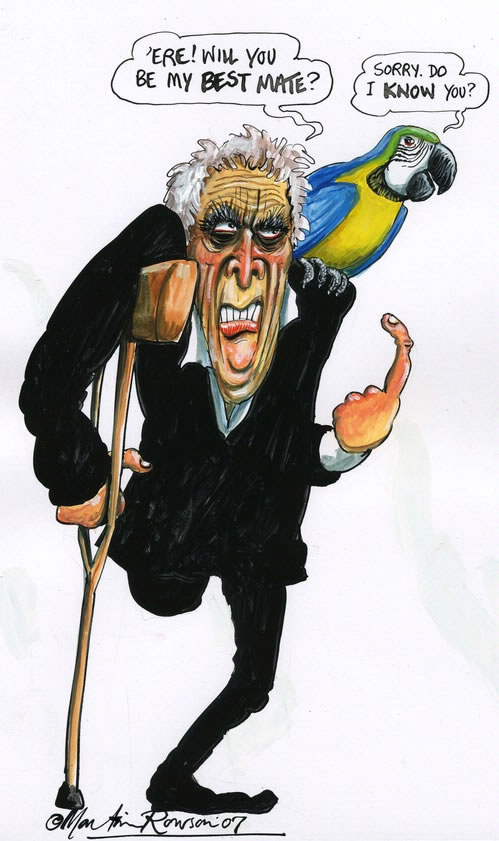

And this lack of knowledge means that most of us are completely unable to name anyone we might rely upon when we are next in serious need of love and comfort. If, for example, I were to fall under a bus tomorrow and lose my right leg, would it really be all right to ring up Celia or John or even Martin or Gordon, mention my misfortune and gently suggest that I’d appreciate a visit or a few words of reassurance? It seems, and once again I quote my sociologist, that our fear that they might respond by wondering why we’d picked them out as the principal recipients of our sad news means that we would prefer to soldier on without any such comfort until we meet up with them casually six months later and apologise for not being quite as active as usual. “Hey, good to see you again, Celia. Sorry about the limp, Gordon. Had the old leg off in an accident some months ago.”

But there is, of course, a quite terrifying dimension to my resolution. Suppose, when I do lean forward and declare my friendship, that Martin or John or Celia or Gordon, or, save the mark, all four of them, stare back in wonderment at my admission. Suppose they patiently explain in the manner of a straight man rejecting an unexpected and unsolicited gay advance that although they like me well enough they never had any reason to suspect that this entailed such a degree of intimacy. Frankly, they might go on, they had their own best friends, and while it would be good to see me around from time to time, on the whole they’d rather not get any closer. No hard feelings, you understand.

My sense of how traumatic this might be is based on a conversation I once had with Robert Robinson about the relationship he enjoyed with his fellow panellist Patrick Campbell on the long-lasting television programme Call My Bluff. After years of working amicably together Robinson had simply assumed that he and Campbell were good friends. Even very good friends. He had no reason to think otherwise. But in one particular programme he chose to refer aloud to Patrick as his friend. After transmission, Campbell came up to him and with the characteristic stutter which so endeared him to viewers asked “W-w-w-hat d-d-did you m-m-mean saying that I was your f-f-friend? I’ve never b-b-been able to s-s-stand you.” Even as he told me the tale I could tell that this had been one of the worst moments of Robinson’s professional career.

But my resolution has taken such a devastating outcome into account. Even if I am rejected by Martin and by John and by Celia and by Gordon, I will at least know where I stand. I will be able to go back to my address book and call up another four possibilities and check out their amicable credentials. One never knows, there may be people out there at this very moment who are itching to have me as a new best friend. Someone to confide in. Someone on whose shoulder they might lean. But not of course too heavily. There’s only so much weight a one-legged man can take.