A visit to the glitzy mausoleum on the edge of Tehran, the final resting place of Imam Khomeini, tells you an awful lot about what matters in contemporary Iran. It is almost completely empty: the odd elderly man playing with worry beads, a couple taking pictures of each other with mobile phones, a pair of gleeful children sliding down the marble stairway in their socks. Though we come in through separate entrances, no one seems bothered when men and women leave through the same exit. The mausoleum is unfinished, like so many buildings in Tehran, and what looks like the base of a crane is left in one corner, as if construction workers had forgotten to remove it before putting the roof on. Khomeini’s tomb and that of his son rest to one side in a glass enclosure, surrounded by gifts of money that bear his face. (Rumour has it that before they made the slots smaller, visitors used to post items somewhat less respectful than small-denomination bills.)

This is my third visit to Iran but it’s the first under the presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Were things going to be noticeably worse? Had the moment of hopeful reformism gone for ever? Very few are depressed enough to think that an attack by America and its allies is the only option left. Most are as critical of the ineptitude of their current government as they are of the periodic bouts of bellicose rhetoric coming from the West. On a day-to-day level, not much has changed, and the moments where the state displays its cruelty and pettiness, although extraordinarily horrible, seem relatively distant from quotidian life for most.

This is my third visit to Iran but it’s the first under the presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Were things going to be noticeably worse? Had the moment of hopeful reformism gone for ever? Very few are depressed enough to think that an attack by America and its allies is the only option left. Most are as critical of the ineptitude of their current government as they are of the periodic bouts of bellicose rhetoric coming from the West. On a day-to-day level, not much has changed, and the moments where the state displays its cruelty and pettiness, although extraordinarily horrible, seem relatively distant from quotidian life for most.

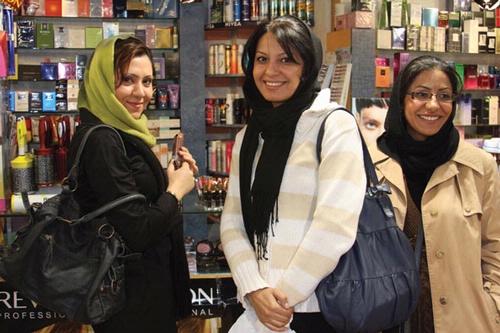

The Tehrani cultural class, in particular, extremely well-educated, well-travelled and forever dashing from one gallery opening to another, seem worlds apart from Ahmadinejad’s tin-pot proclamations about the nuclear programme and homosexuality. But this is perhaps the point: Iran, and Tehran in particular, is an extraordinarily divided place, fractured along class lines, cultural lines and, for women, between those who wear the more casual colourful headscarf and those in the heavy black chador (literally “tent”). Young and middle-class women in the streets of wealthy North Tehran wear the headscarf loosely, sometimes pushed far back to reveal dyed hair and a heavily-made up face, often set off by a plaster across the nose. (Iran has one of the highest incidences of plastic surgery in the world, and the sign of a recent rhinoplasty is a mark of status.)

Drive south – and drive you must, for Tehran, the Los Angeles of the East, is devoted to the car – and signs of relative poverty emerge. Tehran’s characteristically unfinished buildings are even less completed here. Dwellings lean uncertainly against one another, indifferent to the speedy commercialisation, advertising and post-modernity of North Tehran’s architecture and consumerism. On every street you see donation boxes for the poor. Without a well-enforced taxation system, this, along with oil money, is how the government runs its welfare state. Still, not once did we see anyone begging. Child street-vendors try to sell you small items through the car windows – balloons, plasters, light bulbs, napkins, lighters, flowers – but they resent charity, being rather proud of their work.

There is a rigorous split between private and public. A palpable reticence on the streets and the apocalyptic levels of traffic (and pollution), allied with the threat of authoritarian censure, don’t permit easy interaction in the city. The better-off often escape to the mountains which surround the city, both to get away from the smog and to indulge in rather more free social behaviour in low-lit restaurants and shisha cafés (called “hubble-bubble” here). Iran is an extremely young country with two-thirds of the current population under the age of 30 and, while most public spaces in the city don’t allow too much opportunity for flirtation, the handing out of cards with mobile numbers and online contact details is common practice among teenagers, while the odd, rather coquettish car chase is proof enough that banning hormones is something beyond even the most repressive of regimes.

But it’s indoors where things really happen, at the houses of friends, at gallery opening nights, at parties. We’re invited to endless parties. Our hosts are businessmen, journalists, artists. Many Iranians in their 30s have returned after highly successful careers in America and elsewhere, despite their dislike for Ahmadinejad’s regime. We dance to Blondie on New Year’s Eve, drinking black-market spirits and home-made wine, which gives you an instant headache. Iranians know how to party. When one talks to entrepreneurs in their sharp suits, like something out of Wall Street, the image of Iran as a ubiquitously religious state seems a million miles away. Despite its status as an “Islamic Republic”, Iran is surprisingly irreligious, at least when it comes to official religion. Mosque attendance is low, and all the religious or national sites we visited, such as Khomeini’s mausoleum, were virtually empty.

The bazaars, however, where you can buy fake designer labels, tags and patches to sew on to clothes, are always crowded, a mixture of the old world and the new. Mounds of dried fruit and lambs’ heads compete with pirated DVDs, mobile phones and computers. Every house we visit has illegal satellite television, which, because totally unregulated, allows you to watch everything from hardcore gay porn to bizarre and hyperbolic soap operas from the Gulf states.

One of the most striking things about Iran is the value it places on cultural life. The chairman of the Iranian parliament, for example, is also the translator of Kant’s Prolegomena. Many in power pride themselves on reading Heidegger and Plato alongside the Koran.

Iran publishes more books than any other country in the region and an obsession with design and beautiful objects means that the written word is highly fetishised. Iran’s place outside the main circuits of global capitalism and copyright laws has created an idiosyncratic culture industry that fuses older Persian culture with modern computer and print media. The internet plays a strong (if heavily censored) role in the lives of the highly technologically literate middle classes, and an explosion in the popularity of blogs and social networking sites creates connections faster than the government can shut them down.

Iran is a country that talks about itself constantly, whether ruefully and pessimistically or with hope for the future of one kind or another. Everywhere we went, Iran quickly became the main topic of conversation. One student I met spoke of his affection for technology, education and Enlightenment ideals. But when asked about a potential invasion by the US his tone changed completely: “I’d be first to the front line.”

We visit the graveyard of many of those young men who fell at a different “front line” twenty years ago. Just outside Tehran is a huge cemetery primarily for those killed in the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-88 (estimates put total deaths at one million). It is a peaceful, heartrending place, with often personalised graves stretching as far as the eye can see. Hundreds of boxes containing the personal effects of soldiers, their faces etched on their gravestones, are a reminder of how many families still mourn.

We visit the graveyard of many of those young men who fell at a different “front line” twenty years ago. Just outside Tehran is a huge cemetery primarily for those killed in the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-88 (estimates put total deaths at one million). It is a peaceful, heartrending place, with often personalised graves stretching as far as the eye can see. Hundreds of boxes containing the personal effects of soldiers, their faces etched on their gravestones, are a reminder of how many families still mourn.

Some still visit the graves of sons, brothers and fathers every day, washing down the tombstones and throwing fresh petals on to the marble. Interspersed between the graves are giant, gruesomely vivid photographic posters depicting the war. There is a note of heavy romanticism in some, like one of a dying soldier being cradled by his comrades. Murals across the city similarly celebrate, in a heavily stylised way, the deaths of martyrs throughout Iranian history. Reminders of death are everywhere, and Iran seems at its most distant from Western culture at these points, though perhaps this tells us more about our own inability to deal with mortality than anything else.

What can one say about the general mood? The viciousness of the state apparatus, combined with its frequent ineptitude, seems to create an atmosphere of low-level wariness tempered primarily by scorn: there is intense pride and respect for the country itself, but very little for those that currently govern it. Every Iranian I met was more than able to make a distinction between the population of a country and the foreign policy decisions of its government. Despite the occasional piece of “Marg bar Inglistan!” graffiti (“Death to England!”), the idea of blaming British visitors for the policies of their leaders is absolutely out of the question. People often joke about how Britain is still pulling the geopolitical strings, as it was during the bitterly remembered deposition of Mossadegh in 1953, but no one seems really to believe that.

Iran may be interested in some of the things we associate with “the West” – technology, communication, fashion – but it does not appear to model itself on the west. Clichéd images of Iranians as either fanatical Islamic fundamentalists or hungrily clamouring for Western deliverance are both dangerously misleading. The fascinating mix of old and new in downtown Tehrani bazaars, the micro-politics of the headscarf (so different from the situation in France that Joan W Scott describes elsewhere in this issue), the jokes about the idiocy of the Mullahs, attest above all to Iran’s intense particularity. We must take Iran on its own terms, and not on ours.