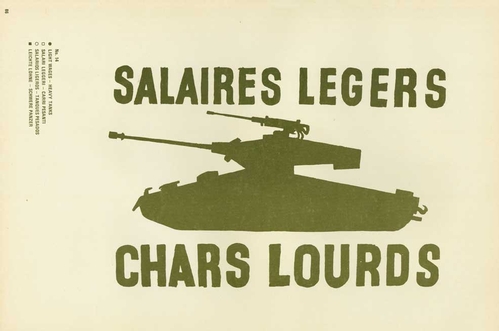

Forty years ago this month, as barriers went up on the streets around Paris, swathes of lyrical slogans started to appear on its walls. “Do not adjust your TV set, there is a fault in reality”; “We don’t want a world where the guarantee of not dying of starvation brings the risk of dying of boredom”; “We are the writing on the wall”. The handiwork of militant students possessed neither of party cards nor of clearly fixed doctrines, the phrases would survive the events and become emblematic of them. For better or worse, May 1968 would go down in history as a revolt of poets.

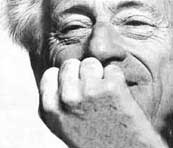

A disproportionate number of these poets hailed from the new university of Nanterre, where they had been the students of the charismatic sociology teacher Henri Lefebvre. A one-time associate of both the Surrealists and the Situationists, a former taxi-driver and a former distinguished resistance fighter (and in the meantime, a still notoriously virile ladies’ man), the roguish Lefebvre had arrived at Nanterre shortly after its 1964 inception, following a stint at the other major centre of late-’60s French student unrest, the University of Strasbourg.

A disproportionate number of these poets hailed from the new university of Nanterre, where they had been the students of the charismatic sociology teacher Henri Lefebvre. A one-time associate of both the Surrealists and the Situationists, a former taxi-driver and a former distinguished resistance fighter (and in the meantime, a still notoriously virile ladies’ man), the roguish Lefebvre had arrived at Nanterre shortly after its 1964 inception, following a stint at the other major centre of late-’60s French student unrest, the University of Strasbourg.

In his book L’irruption de Nanterre au Sommet, written shortly after the events of May 1968 as part of a wider French attempt to interpret them, Lefebvre would describe Nanterre’s campus at the start of les événements as the kind of place where “unhappiness takes shape”. Set in a featureless landscape in the midst of a bitterly lingering shanty-town, the institution was served by a train station signposted “Nanterre La Folie” after the name of the village where the campus was located. The sobriquet was ironic and not wholly false: as eyewitness reports from the time later testified, Nanterre did indeed have a madness: a dull kind of psychosis, of a type characteristic of the provincial offices where Nanterre’s graduates would later work.

“[Nanterre] is an enterprise,” Lefebvre wrote, “devoted to the production of averagely qualified intellectuals and ‘junior cadres’ for this society... the buildings express the project and inscribe it on the ground.” For Lefebvre, the university was equivalent to a kind of offshore intellectual factory, and its location and structures both reflected this fact and produced precise fantasies. Attending a “Parisian campus outside Paris”, Lefebvre argued, led the students of Nanterre to romanticise cities in general and invest their political hopes in a renewed urban program: “Far off, the city – past, present, future – takes on a utopian value for boys and girls installed in a heterotopia that generates tensions and mesmerizing images.” At once elsewhere in space and so longed-for in time, with effort utopia could yet be reached.

Following his expulsion from the French Communist Party in 1958, and his consequent liberation from colouring inside their lines, Lefebvre would come to make this kind of spatial perspective his own. Arguing that the political logic of a given society was contained in its spaces like fire in iron, and then burnt into its citizens like branding on cattle, Lefebvre would pursue his inquiries into the wages of space until the end of his life, in 1991.

Following his expulsion from the French Communist Party in 1958, and his consequent liberation from colouring inside their lines, Lefebvre would come to make this kind of spatial perspective his own. Arguing that the political logic of a given society was contained in its spaces like fire in iron, and then burnt into its citizens like branding on cattle, Lefebvre would pursue his inquiries into the wages of space until the end of his life, in 1991.

The three volumes of the Critique of Everyday Life occupy a pivotal place in the sprawling body of work he left behind. Written over a period of forty years, the books have been newly reissued by Verso in paperback to mark the anniversary of May 1968. As if in a darkened mirror, the books have the effect of explaining that event by negation: although never touching upon May ’68 directly (two of these volumes preceded it) their fundamental concerns nevertheless swirl around it. The same themes and processes which Lefebvre addresses in these texts formed the real-life furnace in which May ’68 would emerge.

In an interview given to his disciple Kristin Ross in 1983, shortly after the completion of the series, Lefebvre explained that his goal with the books had been “to create an architecture that would itself instigate the creation of new situations”. Like Le Corbusier before him (who once memorably claimed that “architecture is everything”) Lefebvre’s definition of architecture extended beyond individual buildings, to encompass the spread of lived structures more generally. From the advice columns of magazines to the ritualised services of the Catholic Church, through to the feeling of optimism that followed the end of the Second World War, and the birth of consumerism and then mass computing, for Lefebvre, architecture was that which, by tapping out rhythms and scales in individual lives, cumulatively worked to shape society as a whole.

This was what Lefebvre meant by his concept of “everyday life”. According to his analysis, the heart of a society, both its virtues and faults, is wound up and reset every day in the sphere of the ordinary. “Daily life,” he would write, “cannot be defined as a ‘sub-system’ within a larger system. On the contrary: it is the ‘base’ from which the mode of production endeavours to constitute itself as a system, by programming this base.” Under contemporary conditions this programming carried the stamp of a specifically capitalist logic, which had overlaid everyday life and effectively colonised it. “Daily life replaces the colonies,” he wrote, “capitalist leaders treat daily life as they once treated the colonised territories: massive trading posts (supermarkets and shopping centres); absolute predominance of exchange over use; dual exploitation of the dominated in their capacity as producers and consumers.” As Lefebvre acutely perceived, this process has not been without certain ironies: “Blue jeans,” he would write, looking back to the ’60s, “produced ... in countries ... whose proletariat is super-exploited, were regarded by young people as a symbol of freedom, novelty and independence.”

For both Lefebvre and his many followers, the political path which followed from this stance was clear: if one genuinely wanted to transform society, one needed to intervene on the level of everyday life, and reverse-engineer its governing architecture. Public space itself needed to be “diverted”, its meanings transformed by those who use it. It was this vision that Lefebvre and the soixante-huitards shared. As one of les événements’ most famous slogans would put it: “Beneath the paving stones – the beach.” Underneath, yet hidden by a “diabolical” capitalist lattice, a more authentically human mode of life still resided, and this mode remained to be accessed if the dominant program was hacked. The wave of occupations which characterised May ’68 can be explained on this basis. As militants wrote above the entrance to the occupied Odéon, “When the National Assembly becomes a bourgeois theatre, all the bourgeois theatres should be turned into national assemblies.”

For both Lefebvre and his many followers, the political path which followed from this stance was clear: if one genuinely wanted to transform society, one needed to intervene on the level of everyday life, and reverse-engineer its governing architecture. Public space itself needed to be “diverted”, its meanings transformed by those who use it. It was this vision that Lefebvre and the soixante-huitards shared. As one of les événements’ most famous slogans would put it: “Beneath the paving stones – the beach.” Underneath, yet hidden by a “diabolical” capitalist lattice, a more authentically human mode of life still resided, and this mode remained to be accessed if the dominant program was hacked. The wave of occupations which characterised May ’68 can be explained on this basis. As militants wrote above the entrance to the occupied Odéon, “When the National Assembly becomes a bourgeois theatre, all the bourgeois theatres should be turned into national assemblies.”

This idea of cultural hacking – what Lefebvre’s one-time Situationist allies referred to as “détournement” – originally provided the impetus for the infamous “swimming pool” incident that scandalized Nanterre in January of 1968. As part of a plan to disrupt the official opening ceremony of the university’s new Olympic-sized swimming pool, radical students led by Daniel Cohn-Bendit planned to greet the visiting notable, the Gaullist minister of youth and sport François Misoffe, with a watery “orgy-in”. Alas, in the event this was not to be, and so instead it fell to Cohn-Bendit to confront the minister directly. “Minister,” Cohn-Bendit declared as Misoffe finished cutting the ribbon, “you’ve drawn up a report on French youth which is six hundred pages long but there isn’t a word in it about our sexual problems. Why not?” “I’m quite willing to discuss this matter with responsible people,” the nonplussed Misoffe replied, “but you are certainly not one of them. I myself prefer sport to sexual education. If you have sexual problems, I suggest you jump in the pool.”

Here was a clash of philosophies as much as one of personalities. Influenced by Lefebvre, whose sometime student he was, as well as by the work of the renegade Freudian-Marxist sexologist Wilhelm Reich, Cohn-Bendit’s claim was that the sexual problems of students like himself were really collective and social problems, for the reason that it was none other than modern capitalist society itself, with its seductive forms of media and desire-inciting advertising campaigns, that came-up with the moulds and the standards for sexual practice.

Whether or not Cohn-Bendit was entirely right about this, it was nevertheless on the sexual issue that the May revolt pivoted. For the students at Nanterre, beginning their careers in militancy by demanding the right for the male students to enter the female students’ dorms, it was in response to the problem of sexual liberation that collective political action was initially forged, and it came to serve as a touchstone for the issue of the repression of everyday life more generally. “The sexual was to be transformed in the process of transforming life,” wrote Lefebvre. “This is no way excluded pleasure, but included it in a larger project, a higher quest.”

If sexuality provided the soixante-huitards with much of their animus, it would ultimately prove a double-edged sword. As Lefebvre unhappily observes in his third volume, following May ’68 the deeper issues of sex dropped out of the equation, leaving only “a permissive society without boundaries or values”. “In the event,” he writes, “it was in these years that the sexual entered completely into the world of commodities, and sexuality became the supreme commodity.”

As history would have it, the capitalist recuperation of sexual liberation would ultimately prove only one amongst many. Today, the soixante-huitard architect Constant’s visionary dream of New Babylon finds its clearest expression in the equally visionary pleasure zones of Dubai, while détournement has become the mainstay of advertising, and the “street artist” Banksy the toast of the auction-houses.

As history would have it, the capitalist recuperation of sexual liberation would ultimately prove only one amongst many. Today, the soixante-huitard architect Constant’s visionary dream of New Babylon finds its clearest expression in the equally visionary pleasure zones of Dubai, while détournement has become the mainstay of advertising, and the “street artist” Banksy the toast of the auction-houses.

What has caused this to happen? According to Lefebvre, “it is not enough to blame capitalism, commodities, and money, [or] ‘bourgeois’ society, for being dehumanising and oppressive.” Rather, the salient fact to be recognised is that a great deal has changed, to the point where the models upon which previous forms of protest depended no longer hold sway. Marxism now only has influence within the academy, while the expansion of the computer revolution has caused the kinds of collective spaces upon which May ’68 was grounded to melt, as it were, into the MacBook Air. “After the Liberation,” writes Lefebvre, “the ‘people’ still had a meaning in France... Over the next 15 years, this unity began to break up not into clearly differentiated and opposed classes, but into layers and strata.” Over the next 40 years after that, this fragmentation has only increased, according to a dynamic of privatisation and third-way managerialism that has worked to transform the classical figure of the citizen into the more contemporary conception of “the user”.

And yet for Lefebvre himself, writing the Critique of Everyday Life in 1981 with a tone of tragic authority, these discontinuities have gone hand in hand with an equally profound continuity. Most especially in the realm of rational thought, where the twin enemies that have perennially dogged it remain largely unchanged: mysticism, which proposes concepts that do not “correspond to the deepest level of reality”, and which therefore provides the fodder for the worst kinds of reaction; and dogmatism, which Lefebvre maintains “must be hunted down in every nook and cranny and dragged from its hiding place by the tail like a rat.” “Critical analysis,” Lefebvre concludes, “begins with the disenchantment of the state and the sphere of power. They have nothing magical or sacramental about them... To traverse daily life under the lightning flash of tragic knowledge is already to transform it – through thought.”