Dolce and Gabbana set the tone on the autumn catwalks with show-stopping plaid ruffles and pussy bows inspired by the Queen. Roberto Cavalli flaunted clashing checks over leopard print tights. Ralph Lauren made squares preppie. Vivienne Westwood, the original alchemist who transformed prim to punk, has once again declared her passion for tartan.

It’s the new black, blaring its blatant hues from Paris and Milan to Marks and Spencer and Primark. Tartan is evident in everything from oversize blazers, shift dresses and trousers to mini skirts, tights and even trainers, with the latest Nike Air model covered in clashing clans.

But the infatuation with tartan is cyclical rather than revolutionary. There are mini revivals every couple of years; it never really goes away. Tartan is one of the most abiding of textiles and the most adaptable. It works as school uniform or high fashion, military garb or grunge, in country house or bordello.

And, according to Jonathan Faiers in his comprehensive new book Tartan, it’s characterised by contradiction: tartan signifies conformity and rebellion, monarchy and republicanism, order and anarchy, purity and licentiousness, the sacred and the profane. Its many meanings and associations clash as wildly as the patterns it inspires.

No other textile has ever acquired anything like the instant recognition, the multiple meanings and the abiding loyalty that tartan attracts. And in his wonderfully eclectic study, Faiers shows it to be a powerful example of how myths are made, traditions manufactured, identities reshaped; how even allegiances and faiths can be constructed according to the dictates of politics and power.

He delights in knocking down received ideas, beginning with the common assumption that different patterns, or setts, are associated with rival clans. This notion, he argues, was not developed until the 19th century, when the urge to document and classify collided with romanticism. Historians wanted to establish dynastic links between clan and pattern in order to satisfy their own version of Scottish identity. But, says Faiers, it’s far more likely that the different patterns emerged from different regions, according to whichever dyes and skills would have been locally available. Some of these probably became associated with the families who lived there.

In his analysis, Faiers pays tribute to the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, whose ground-breaking essay “The Invention of Tradition: The Highland Tradition of Scotland” demolished the romantic idea of tartan as a flag or badge of a clan, demonstrating just how far sentiment may influence the making of such myths.

This didn’t stop generations of those with Scottish backgrounds or Scottish pretensions eagerly claiming family tartans; even today there’s a flourishing heritage market feeding appetites for historic links to celebrated dynasties – with thousands seeking entitlement to the Royal Stewart insignia. Modern Scottish football teams tend to adopt tartans compatible with their colours. But the national team’s Tartan Army sett interweaves the two most popular tartans, Royal Stewart and Black Watch, in a deliberate attempt to unite clannish rivals Rangers and Celtic and to mask the religious bigotry and sectarianism that divide them.

However spurious these clan connections may be, though, tartan is undeniably Scottish. Which is why it came to be regarded as a symbol of rebellion by the English monarchy after the Act of Union between England and Scotland was passed in 1707. This led to a spate of Jacobite uprisings, culminating in the failed rebellion by Bonnie Prince Charlie at Culloden in 1746. Following this defeat tartan was banned in Scotland by the Act of Proscription, a stricture so comprehensive and so severe that the wearing of traditional Highland dress by ordinary people disappeared, and along with it the traditional craft skills of local spinners and weavers.

Paradoxically, as tartan was forcibly discarded by ordinary indigenous Highlanders, it acquired a new cachet as a fashionable item for the aristocracy and as military wear for the corralled Scottish regiments. “After 1746 tartan production effectively changed into a professional industry under the control of a few key manufacturers, who benefited from supplying the newly formed Highland regiments with the so-called ‘government tartans’. Simultaneously, the production of, and demand for, hand-woven tartan for ordinary Highland domestic consumption virtually vanished overnight.”

It was during this period that tartan changed status from the divine to the demonic. For centuries, it was considered to have mystical qualities, sometimes acting as a charm and sometimes as a curse. Local craftswomen weaving their cloth by hand would sing songs and tell stories as they worked. The process of “waulking” – soaking the cloth in an alkaline solution, then beating and pummelling it to thicken and bind the threads – would be accompanied by almost liturgical chants, the ritual completed with the blessing and consecration of the cloth.

But once tartan became a symbol of dissent and of antipathy towards English rule, its supernatural associations darkened. Highland dress became characterised as a sartorial expression of sedition and lewdness, and tartan most of all became the textile of the devil, just as Bonnie Prince Charlie was dubbed the “Satanic Agent of the Pope”.

The demonisation of tartan was political expedience masquerading as devoutness; as ever, religion had been marshalled in the interests of power. And tartan served a similar purpose in the following century, when a new king embarked on a strategy of rapprochement.

In 1822, in an attempt to demonstrate the unity of his two nations, the newly crowned George IV rode into Edinburgh swathed in tartan, symbolising the consolidation of Scottish nationalism into his own dynasty. The pageant was stage-managed by the hugely popular and shrewdly patriotic Walter Scott. And it worked. From emblem of rebellion tartan morphed, practically overnight, into a symbol of united monarchy.

If George IV used tartan to reinforce his incorporation of Scotland, the invention was taken to absurd extremes by Queen Victoria. Commandeering Balmoral as the royal retreat, she swathed its furnishings in tartan and dressed her whole family in it, not to mention her household staff. Balmoralisation was her crusade to claim a false but potent heritage. Once the Balmoral myth had taken hold, tartan was reinstated as the pattern of kings, the height of convention. From then on it was the most accepted and respectable of textiles, suitable for men and women, for schoolgirls and for soldiers.

When British troops swarmed across Paris and other French cities after the defeat of Napoleon, French onlookers were transfixed by the sight of Scottish troops proudly arrayed in tartan kilts. This, after all, was after a period of sombre dress for men, instigated by the French revolution in response to the excesses of the king and court. Here, suddenly, were uniforms that, without being wantonly flamboyant, were colourful and even suggestive.

And so the French eagerly began to adopt tartan for themselves – in part, at least, as a gesture of defiance against the English: the Celtic cloth asserting solidarity with Catholicism. It was this French fascination with tartan that unleashed a rash of bawdy speculation about the sexual nature of the kilt and what lay beneath it.

Faiers is quick to recognise the sexual promise and ambivalence of the kilt. “An emphasis on freedom of movement and sexually emphatic clothing characterised the first two decades of the 19th century, but it is the kilt that has permanently eroticised tartan. The perceived inherent lewdness of its wearers was put forward as one of the justifications for the proscription of Highland dress.” The kilt was indecent because of its exposing nature, the idea of what might be dangling free beneath it.

But despite these titillating anxieties, it’s hard to detect anything remotely roguish about men in kilts. Maybe it’s just impossible to take seriously an attire that’s been the subject of so many seaside postcards, so many music hall innuendos. It’s just far too Carry on up the Khyber to be a come-on. The prospect of a man’s genitals flapping unfettered beneath his pleated skirt is more alarming than erotic. There’s far more sexual promise snuggled within a well-fitted pair of Calvin boxers.

It’s possible that the early Highland clansmen roughing it in the heather might have bestowed some kind of masculine magnetism on their rugged attire. But that raw physicality disappeared once tartan went smart. Those misguided Scottish (and English) toffs who insist on wearing kilts with their dinner jackets as a version of evening wear have obviously never read Cosmopolitan or they’d know the cardinal rule of undressing: never leave your socks till last. What woman could possibly thrill to the spectacle of white, hairy legs descending from a pleated skirt into thick scoutmaster socks?

In his erudite passion for the pattern, Faiers does somewhat exaggerate the case for tartan’s sexual powers. “Many architects, design historians and cultural theorists,” he claims, “have observed the intersection of horizontals and verticals that are the basic components of any grid system, as also suggestive of physical union. In Piet Mondrian’s early writing, he characterised the horizontal line as representative of the horizon and the earth, whilst the vertical suggested human impact on that space; simultaneously the horizontal also signified female and nature, whilst the vertical signified male and culture, the two vectors’ intersection expressive of both mystical and secular union.”

But the very straightness of these tartan lines belies such an interpretation. The even patterns are just too military to match any claim to sexual import; if tartan were music it would be unsyncopated, confined to major keys, with no minor movements or curves, and written in march time.

Tartan becomes erotic only when it is unexpected, or in some way transgressive. The sexual overtones of the kilt as school uniform are nuanced with the notion that these are little girls dressing up as men who are dressing as women. Royal Stewart becomes suggestive once it’s ripped into punk jeans or stretched over distressed leather; those unbending tartan lines soften into lasciviousness when twisted into the undulations of breasts and buttocks, angles twisted and reshaped to challenge upright convention.

This is what explains the endless reincarnations of tartan by fashion designers seeking to explore and undermine, play with and subvert its many meanings. And Faiers is keenly aware of the tensions inherent in tartan between primness and promiscuity, sexual repression and manifest desire.

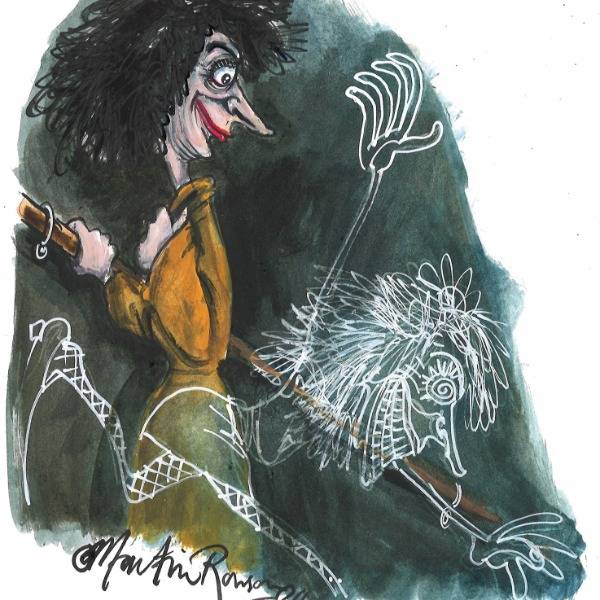

He refers to a Marc Jacobs collection for Louis Vuitton as quintessentially conveying tartan’s ambiguities: “Sensible coats and suits in tartan, prim blouses, capes and stoles were worn provocatively and accompanied by sexually charged tartan accessories that resulted in a collection that conveyed the opposing characteristics of the textile. Simultaneously repressive and liberal, reserved and exhibitionist, these were clothes one could imagine Miss Jean Brodie wearing if she gave up teaching to work in a Berlin brothel, resulting in a kind of ‘erotic frumpery’.’’

But that in no way exhausts tartan’s capacity for containing opposing characteristics within its warp and weft. Vivienne Westwood’s legendary appropriation of tartan celebrates its individualism, while Scottish designer Alexander MacQueen’s “Highland Rape” collection was a comment on its colonial links. And while Highlanders happily flaunt tartan as a badge of identity, it is also sported by those like the Native Americans who were the victims of that same uniform. Even the Scottish plantation owners’ predilection for clothing their slaves in cheap, hard-wearing tartan has not inhibited its incorporation into traditional Caribbean and Afro-American women’s style.

Throughout the world, tartan has been adapted by those attracted to it, whether for its Britishness or its exoticism or its flavour of rebellion. Idi Amin sported tartan as part of his self-appointed title of Last King of Scotland; Mohammed al Fayed has recreated himself as a Scottish laird, dubbed “Mohammed of the Glen”. As late as 1981, North Carolina commissioned its own tartan, Carolina, though avoiding any reference to its more shameful associations. The artists made a portrait in the style of Indian miniature painting depicting their father in his specially commissioned Singh tartan.

And, inevitably, the first “kosher” tartan, commissioned by Scotland’s Jewish community, is about to go into production. Scottish Jewry has always favoured the kilt for ceremonial occasions. They even pipe in the haggis at weddings – though usually in the form of chopped liver rather than pigs’ entrails. Now Jews will be able to go the whole hog. The kosher tartan will be worn not just on kilts but on ties, skullcaps – and even in a kilt pin in the shape of the Star of David. You can’t help wondering what the Jews of Scotland will be wearing under their guilt.

There’s just one significant interest group that hasn’t yet succumbed to the magic of tartan. And it’s high time that humanists shaped up to the challenge. I’d recommend a black background to symbolise an utter rejection of mysticism; then a subtle blend of green for nature, a dominant blue for rational thought, a splash of yellow for sunshine, orange for calm, and a dazzle of clashing reds and purples for passion, love, anger and glorious inconsistency.

There’s just one significant interest group that hasn’t yet succumbed to the magic of tartan. And it’s high time that humanists shaped up to the challenge. I’d recommend a black background to symbolise an utter rejection of mysticism; then a subtle blend of green for nature, a dominant blue for rational thought, a splash of yellow for sunshine, orange for calm, and a dazzle of clashing reds and purples for passion, love, anger and glorious inconsistency.

Tartan by Jonathan Faiers was published by Berg in October 2008.