After my wife Anna Alchuk disappeared in Berlin on 21 March this year, I lived through three weeks under the constant pressure of police investigations, getting used to emptiness next to me and to the ever-deepening abyss which threatened to engulf the rest of my life.

After my wife Anna Alchuk disappeared in Berlin on 21 March this year, I lived through three weeks under the constant pressure of police investigations, getting used to emptiness next to me and to the ever-deepening abyss which threatened to engulf the rest of my life.

I would shudder at the sight of the photos of her with the “Police: help needed” caption which had been put up in cafés, pharmacies and shops. Whenever I caught sight of these notices, I had to turn away because I couldn’t bear to see her face.

And then there was the apartment, in which every object reminded me of her; the streets where every house is linked to shared experiences. How is it possible to amputate a part of oneself? How can one learn to see again without the assisting gaze of the other, which had become so much a part of myself that it was no longer noticeable?

Day in, day out, I played the role of the answering machine: several times a day I explained to the shocked caller that there was actually no news to report, that the search continued and that so far, there was no trace. The voices on the other end of the line then began to tremble, went quiet and transformed into whispers. When I called Moscow, I heard echoing: every sound reverberated, as if I had an additional person listening on the line.

But there was still a muted hope.

Three weeks later on 12 April, two detectives stood outside our door. When they showed me the wristwatch and the black and white photos of items which had softened in the water, I could still doubt that they belonged to my wife, but when I saw the wedding ring which Anna had worn for 33 years (which is the same as the one I wear, just a little smaller), I said first to myself (which was the hardest thing) and subsequently to the police officers: “Yes, it is most probably her.” While I got changed to go down to the station and sign the identification papers, the officers, who had obviously had to witness a lot in their careers, made sure that the door was left ajar, knowing that you can never know what a person in my situation might do.

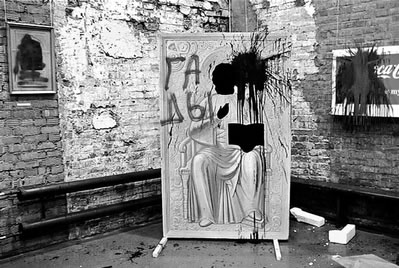

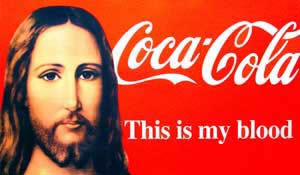

After Anna’s disappearance, I found a book of her dreams from the last five years, during which time she and other artists in Russia were the victims of a hate campaign. On the radio, the television and in the press, bucket loads of mud were thrown at all of them. Then my wife, whose innocence was clear to the court from the outset, was the only one who was prosecuted. After five months of uninterrupted abuse and humiliation in the courtroom the judge, who had not been presented with a single piece of evidence of her guilt, acquitted her of all charges (which is extremely rare in Russia, as acquittals are highly damaging to a judge’s career.)

But an acquittal is only a formal judicial matter. In an authoritarian society somebody who has been smeared with guilt will continually carry with them the stigma of guilt. The Moscow art scene saw who had the power and turned its back on Anna Alchuk.

But an acquittal is only a formal judicial matter. In an authoritarian society somebody who has been smeared with guilt will continually carry with them the stigma of guilt. The Moscow art scene saw who had the power and turned its back on Anna Alchuk.

How did that affect her? How did it happen that she gradually began to grow into her victimhood and to lose confidence in the outside world? She had initially viewed her enforced victimhood ironically and as something external (in 2005, with the trial still going, she made a poetry collage and a video with the title “Responsible for Everything”). I have written lots about social tragedies, about presidents, media strategies and tricks which the powerful use to secure obedience, but this time it was something completely different: a major caesura of contemporary history lay in the fate of a real living person.

In an authoritarian social climate, a person who is declared guilty begins slowly but surely to think of themselves as guilty. They internalise the guilt, not because all others around them are convinced of their guilt (they have friends, even if they can no longer offer their help), but because they were charged as guilty by an authority which speaks in the name of everyone. And so everyone, regardless of whether they think the smear victim is guilty or not, will behave towards them as if their guilt had been long established. The chosen scapegoat begins, with time, to inscribe the guilt on to their own body. At some point the desire emerges to peel off this body, to break out into a space beyond this perverted society which condemned them.

In 2003 when Anna Alchuk was charged with fomenting national and religious conflict, she recorded the following dream in her diary:

“A huge living-box, which was my home, was floating in the open seas near to an anchored leisure boat. My friends and I were both at sea and contemplated events in the distance. Suddenly I saw a fire on the deck of the boat. ‘If the fire is not extinguished immediately, my box will catch fire too,’ I thought. I swam over and tried to spray water onto the fire. But it was pointless. The fire blazed higher and higher. My friends swam over in my direction and signalled to me that I should get away from the fire as quickly as possible. The reflection of the fire became fixed in the water. I woke up and was helpless. Where should I go now?”

The “huge living-box” in this dream represents our old, familiar apartment, which in a widened sense, represents our whole former life which was on the verge of being devoured by the fire of “people’s hate” that was ignited against my wife. This fire cannot be extinguished – that is why her friends warn her. “The box”, her whole former life, has to burn up completely and here the end of the dream poses the most important question, to which there is no answer: “Where should I go now?”

Wherever one seeks refuge in such a world, there is none to be found. The insecurity and the feeling of being defenceless and at the mercy of others eventually gain the upper hand. She dreamt of a war breaking out and the world being in flames and the most important thing was to rescue the children from a burning house. My wife wrote up this dream on 17 October 2006, a year and a half after the trial against the organisers of the “Caution: Religion!” exhibition.

“I am standing next to a stone wall, behind which a fire is raging. Soon the fire will jump over the wall. I have to get away as soon as possible. But the most important thing is to take the children with me. ‘Faster, faster,’ I urge them. Then we are standing in front of an underground bunker. We cross the threshold and then the doors close behind us. ‘One more minute and we would have been dead,’ I think, relieved. In the second dream, the world was about to be destroyed. I have to get dressed and go away...”

In the Lotus Sutra, there is a parable about children in a burning house, and the “skilful means” (upaya) which their father (Buddha) uses to try and coax them out of it. To encourage the children to leave the “burning house” of the three doomed worlds, Buddha promises them a beautiful toy. In Buddhism, salvation, the path to freedom, has no tangible equivalent. A way out can only be found when one perceives that what until recently appeared impenetrable and immovable, real and tangible, is actually unreal, illusory and a dream. Hell and paradise are merely forms of experience, one and the same. They have no autonomous existence and can abruptly make an appearance, in dreams or when awake. But despair is nigh for those who imagine too vividly the escape from a burning house into freedom.

”I know there will be a war soon,”

my wife dreamed on 26 October 2004, shortly before the investigations were due to close and the court cases begin,

“and that I won’t need any good clothes any more. I’ll take them off and just keep the warm things. A boy of fifteen or so is with me... It is high time we close the door, shut ourselves off from this terrible world. The boy and I close the doors, secure them with heavy bars. But the feeling lingers that this will not offer us enough protection.”

In another dream the danger comes from elephants that have just left a huge room but could return any minute.

“I went from one room into the next, checking how secure the doors were – in short, I was looking for a safe place.”

Slowly but surely Anna Alchuk internalised the hate which was initially directed against all the participants of the exhibition, and turned it on herself like a laser beam. Hate, the foreign body, worked its way into her imaginary world. Defence witnesses, lawyers and friends who came to support the victims of arbitrary persecution were insulted in the court buildings by “Christians of deep conviction” (as the public prosecutor described them) as “pig Jews” and forced to disappear from Russia before it was too late. My wife (a half-Jew who was not raised religiously, who spoke neither Hebrew nor Yiddish, who was unfamiliar with Jewish culture and had never set foot in a synagogue) was confronted by increasingly aggressive invective from those who were on the side of the prosecution. She began to feel more Jewish and absorbed the hate that was being directed against her. In one of her dreams she is being strangled by a painter acquaintance, and she knows this is happening because she is Jewish. In another dream she explains to a publisher, who until recently was a friend of ours and who is now publishing anti-Semitic literature, that she is half-Jewish and she will never be able to forgive him for this betrayal.

My wife loved people and needed human warmth; she was incapable of hating anyone and had never learnt to do so. But where can you run from a hate that is proclaimed in the name of the state, which is backed by a Duma resolution (the upper organ of the Russian legislative system had condemned the exhibition “Caution: Religion!” long before the case opened), and taken up by generals, TV presenters, intellectuals, journalists and artist colleagues? You can break off contact with individuals (in the years when Putin was in power we lost about half our friends), but hate which is raised to a social behavioural imperative is inescapable, because it is ubiquitous.

My wife loved people and needed human warmth; she was incapable of hating anyone and had never learnt to do so. But where can you run from a hate that is proclaimed in the name of the state, which is backed by a Duma resolution (the upper organ of the Russian legislative system had condemned the exhibition “Caution: Religion!” long before the case opened), and taken up by generals, TV presenters, intellectuals, journalists and artist colleagues? You can break off contact with individuals (in the years when Putin was in power we lost about half our friends), but hate which is raised to a social behavioural imperative is inescapable, because it is ubiquitous.

As a talented poet, my wife relied on a state in which her soul was merged with the world, and now the source of this blissful happiness – her trusting way, her openness, friendliness, her unique form of naivety – had run dry, disappeared, drowned in the powerful current of hate directed towards her. In her dreams, the dreams of a person who is exposed to a hate campaign, her feelings of guilt grew and with this, the need to punish herself. The fact that this hate had initially used obviously crazy people as its tools turned out only to be further proof of the inevitability of the sentence being enforced – quite independent of what the court might decide. Essentially, Anna Alchuk was not condemned by a court, but by all those powers which, under Putin, took care of enforced conformity in Russian society (culture included). Once acquitted by the court, she saw herself facing a community for whom the things for which she had fought and made sacrifices had completely lost their meaning. Over these years the art scene resigned itself to its defeat and even managed to profit considerably as a result. It was, it transpired, far easier to endure being a target of religious fanatics than having to put up with the repressive passivity of most of her fellow artists.

The horrific thing about authoritarian societies is that everyone lives in a seemingly no-win situation, which is why no one can be held accountable for their actions. For those who are actually decent human beings, capitulation becomes essential to survival. Under such conditions, depoliticisation and a humble attitude become a firm political stance. Any individuals who refuse to play along are silently sacrificed, ousted from the social network. They are then exposed to the danger of identifying with the image of themselves that has been forced upon them; they run the risk of becoming what they are perceived to be. Having absorbed the collective guilt, they live in fear of becoming the sacrifice which the losers offer the winners.

After her tragic death, my wife was described by many foreign journalists as a “Putin critic”. I doubt that the name Putin appears in anything she has ever written. She had no interest in politics. But when politics forced its way into our space and started to destroy it, when things were taken away from us that shortly beforehand had seemed to belong to us, my wife, myself and other (sadly only a few) intellectuals who defended their language and their right to artistic expression were suddenly labelled “Putin critics”. The “Art and Taboo” conference which the Sakharov Centre in Moscow staged in October 2007 illustrated the new situation very clearly indeed. Not a single Moscow artist of any standing was to be found at this conference; the crucial problems of the Moscow art scene were discussed by a handful of curators and art critics, most of them foreigners. For Anna Alchuk, this was a further sign of her abandonment, an additional indicator that the powers behind the hate campaign waged against the participants of the “Caution: Religion!” exhibition had gone out and taken over the cultural sphere which, from that point on, was no longer our terrain but theirs. This meant that all sacrifices were in vain.

Anna Alchuk’s diary of dreams shows that being a “Putin critic” is a life-threatening occupation. She lived in constant fear of my life and her own. The following excerpt is only one of many examples:

“Misha [this is my name] and I are at some social gathering among a big group of people. Out of no where fascists (I have no doubt that they are fascists although they are wearing neither uniforms nor swastikas) start laying into Misha. No one tries to help him. I suddenly realise that we are completely vulnerable in this crowd of people.... I feel help less and dejected. There is no way out any more.”

A further diary entry, dated 30 April 2003, at the peak of the hate campaign against “Caution: Religion!” reads:

“Misha talks very harshly and openly about politics. I see a machine gun aimed at him. I know that they want to get rid of him and I protect him with my body. Then they shoot me. Everything around me goes dark and I smell the scent of Misha’s aftershave. Does that mean I’m completely dead? I ask myself.”

The motif of vulnerability grows ever stronger, even after the acquittal. No statement of the court can protect her against this channelled “anger of the people”, particularly because, in this new phase, she has already internalised the anger. In the dream, first water then blood spills from her body:

“I find myself behind a sort of curtain in a tent,”

it says in a diary entry from 31 October 2007.

“Suddenly water is flowing out of me and the water contains traces of blood. More blood is coming out all the time and it attracts hordes of angry people who flock towards me like vultures. I immediately realise they want to kill me because they think I am a witch.”

In this dream, she has already started to see herself as others see her; she perceives the aggression of the mob as an act of retribution. After a certain point in time the logic of the system eludes not only social rules, but also a healthy mind. Things that were dearly cherished before are now perceived as a hindrance; the last supports that might have given the dreamer a hold in the world collapse.

We should however – this is the most important conclusion – view this phase neither in isolation from those that preceded it, nor as a part of the supposedly inevitable progression of somatic illness. My wife was not a psychologically disturbed person; she was just unable to withstand the “fury of the people” which was directed at her, which threw her out of her immediate surroundings. Had her surroundings not mutated, and instead lent her support, my wife would most certainly have recovered and lived for many years to come. Unfortunately, though, she had become leprous in the eyes of many; people let her fall and she lost her place in the world.

Institutional strategies, when they come into effect, do not impact other institutions but human beings, who are highly sensitive or thick-skinned, fragile or robust. After the death of my wife, who was a tender, fragile being in this increasingly brutal world, I asked myself for the first time about the price of an intellectual position, however valuable the content of this position might be. Should it be paid by the life of another person when this person might share its tenet but cannot withstand the psychological pressure?

Today I am much more sympathetic towards the editor of Novaya Gazeta who, after the murder of the journalist Anna Politkovskaya, wanted to shut down the paper because no intellectual position could ever stand above the loss of human life.

First published in German by Lettre International (Summer 2008). First published in English by Signandsight.com. English translation by Nick Treuherz and LP. With thanks to Signandsight and Michail Ryklin