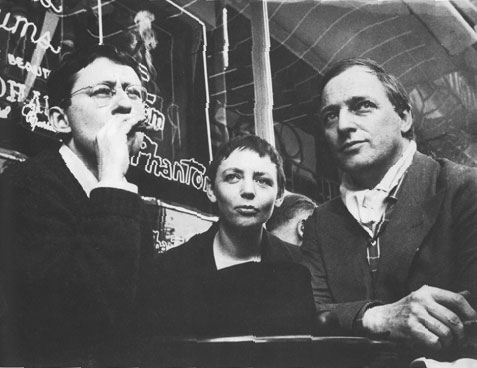

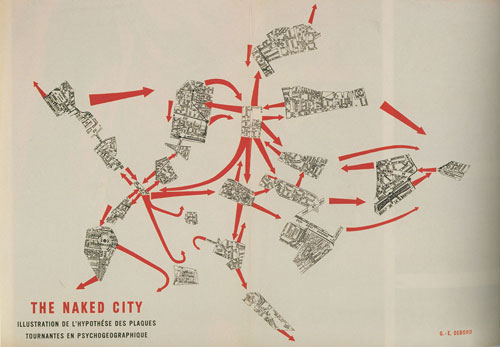

The Situationist International, or SI, was a small gathering of would-be poets, filmmakers, artists, déclassé bourgeois and lumpen troublemakers, who first met and conspired in the hothouse atmosphere of Left Bank cafés in the 1950s. Its members were perhaps the last Bohemians, renouncing such practicalities as work in favour of long days – and nights – of wine, hashish and explorations of the city that privileged getting lost over orientation. They called the technique dérive, which means drifting, like an unmoored ship caught in the treacherous currents of the urban ocean. It was part Surrealist promenade and part close-to-home ethnographic expedition, and led to an alternative mapping of the city in which “psychogeography” – the emotive states called forth by different neighborhoods – seemed more significant than income distribution or the ratio of indoor toilets to residential density.

This could all seem like so much youthful extravagance, and indeed the latter was not lacking, but a more serious purpose underlay the SI’s fanciful, and often heated, rhetoric. The 1950s saw the triumph of urban renovation in the name of social “progress,” which in practice meant the clearing of slums in order to make Paris safe for the middle classes. As new towns sprouted like mushrooms in the suburbs, the city centre was remade as a boutique and a museum. Against this trend, the SI celebrated life at street level, called for cities free from the scourge of the automobile, and insisted that architecture should be filled with passion, not sterile rationalism. They also set out to discover those remaining islands of urban diversity, the little enclaves of Spanish refugees from Franco, or the North African shantytowns that harboured guerrillas who would fight for Algerian independence. This geography of resistance, and the ways in which its everyday life created an environment suited to its existence, inspired the SI to develop a theory of revolution in which the city played a central role.

In this situationism drew on a rich history of ideas about the liberating city that for centuries has seemed to offer a vast field of possibilities, the chance to reinvent oneself and to make a new life unencumbered by the dead weight of tradition, family and provincial mores. While this idea of the city is in many ways a myth – the city is also the place of huge inequality, squalor and oppression – it is a potent myth that can inspire action.

For no city is this more true than Paris, where successive revolutions have taken to the street in the name of the dispossessed’s right to the city. From the sans-culottes of the French Revolution to the Communards of 1871, the poor of Paris set out to create a new life by reshaping its urban setting. These revolutionary politics have also had an echo in French culture, from the poet Arthur Rimbaud’s gutter fantasies of the 19th century to the erotic wanderings of the Surrealists in the 1920s. The Situationists embraced in equal measure both the poetic and political mythologies of the city, and carried these traditions into the later 20th century.

Their ideas can be charted along two main axes. The first was the drafting of blueprints for the city of the future, the visionary planning of post-revolutionary urban life. A Dutch member of the group, Constant Anton Nieuwenhuys, who went by the name of Constant, spent almost two decades designing his “New Babylon”, an ever-expanding lightweight structure suspended over the earth’s surface; its interior was completely flexible, so that residents could alter their surroundings at will. If today its conception seems rather quaintly naïve, if not faintly nightmarish, we should not be blind to its polemic intent in an age accustomed to celebrating the latest concrete behemoths of modernist design. By comparison, New Babylon’s titanium piers and nylon sheathing look open and adaptable to the desires of its inhabitants. Coupled with the complete automation of industry, Constant’s city promised a future in which humanity would devote itself to the playful construction of its world. If the very scale of New Babylon’s ambition ruled out its realisation, the vision of a city devoted to play directly inspired later movements like the “Provos” of Amsterdam, who set out to revolutionise the city on a more modest level, with free bikes and the occupation of abandoned buildings.

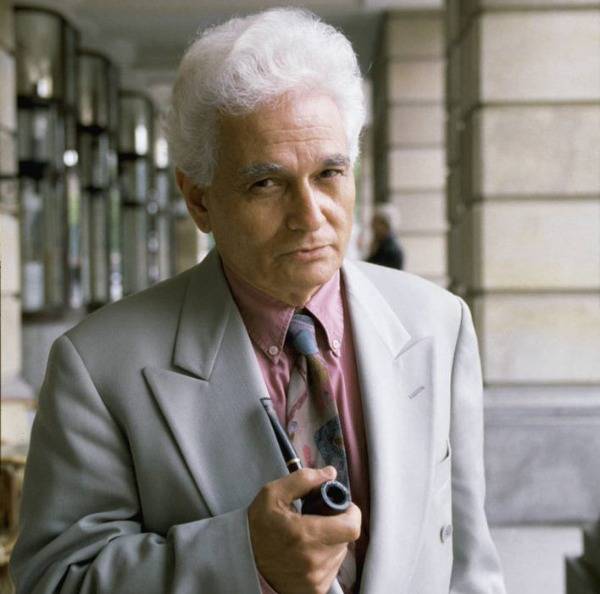

The second axis, which in the end supplanted the openly utopian aspirations of the Dutch designer, devoted itself to the unforgiving critique of the city that postwar capitalism had bequeathed its citizens. From the dormitory towns built in the 1950s to accommodate the influx of residents to the Parisian metropolis, to the urban insurrections that gripped America’s inner cities by the middle years of the 1960s, the SI kept a close watch on the latest developments in urban planning and on the resistances it generated. Here it was the Frenchman Guy Debord’s voice – eloquent in its chilly anger – that predominated, culminating in his 1967 book The Society of the Spectacle, which included a chapter on “territorial planning” as a technique of separation and disempowerment. He and his fellow Situationists eschewed dictating the form that social transformation might take, and indeed there is a notable lack of positive proposals from this moment; however, their fundamental beliefs dictated a nonhierarchical, democratic and collectivist organisation free from specialisations and separations. Their inspirations lay in the Commune and the workers’ councils of Spain and Hungary. But no matter how distinct Debord’s unforgiving critique was from Constant’s dreaming, they both agreed that no revolution worth its name could ignore the city.

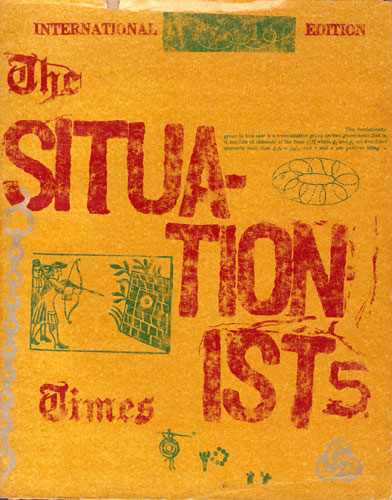

Although the SI spent a good deal of its energy defining itself through vituperative attacks upon the stars of the French intelligentsia of the 1960s – its condemnations of Barthes, Althusser, Lacan, and Godard are infamous, and frequently hilarious – it did not exist sui generis. Situationist politics bears close comparison with the “revolutionary romanticism” of Henri Lefebvre, who was also coming to terms with the urban nature of modern life in these years. Like Lefebvre, the SI looked back to the writings of the early Marx and insisted that revolution was not only about changing control of the means of production, but also about changing control over our lives – that social change happened in the street and everyday life as much as in the factory and work. That may seem self-evident today, but at a time when Stalin’s shadow still loomed large, and when fashionable philosophies of anti-humanism predicted the “death of man”, the Situationist belief in people’s ability to effect concrete historical change was truly radical. So was their enthusiastic embrace of city as the space of historical change, which went against the grain of a long tradition of suspicion if not hostility towards the city from the Left, stretching from William Morris down to Lewis Mumford. Rejecting this anti-urban thought, the SI saw the city as the locus of those social contradictions that would one day explode in revolutionary change.

Their prognostications almost came true in the Parisian uprising of May 1968, but the SI’s dream did not die with the failure of the students and workers to topple the government during that heady month. Indeed Situationist writings on the city seem more relevant, and necessary, than ever, as our urban landscape is given over to gentrification, privatisation and the imposition of security measures guaranteeing ever more surveillance and policing of the population. You can hear the echoes of the SI in some of today’s most radical voices among the anarchist Left, but perhaps more importantly, you can see the evident truth of many of their conclusions by simply taking a close look at the city around you: the ghettoised suburbs and “no-go” zones of our metropolises were first mapped in their writings over four decades ago. Their combination of hardheaded analysis and poetic fantasy seems just what our disillusioned moment requires – an infusion of intransigence and utopia. Until city air really does make us free, the Situationist critique will remain a crucial instrument for remaking our urban space in a more human, and humane, image.

The Situationists and the City, a collection of original Situationist writings and design, edited by Tom McDonough, is published by Verso