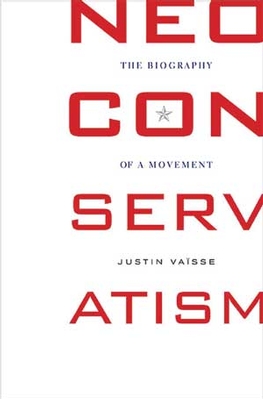

Neoconservatism: The Biography of a Movement

Neoconservatism: The Biography of a Movement

Of all the remarkable and horrifying things about the group of American Republican neoconservative hawks who cheered America’s efforts to bring democracy to the Middle East at the barrel of a gun, not the least is their durability. There were good grounds for believing that that as a result of the disaster of the initial occupation of Iraq – a disaster that reflected appalling failures both of analysis and of planning on the part of the leading neocons – the movement would be finished as a serious force in American affairs.

Yet, as Justin Vaisse points out in his excellent study, nothing of the sort has happened (as Shadia Drury predicted in these pages back in 2007). The foreign policy team of John McCain in the 2008 elections was dominated by neoconservatives – and had it not been for the economic recession, McCain would probably be President today.

Neoconservatives remain prominent and even dominant throughout the foreign policy establishment of the Republican Party, while their moderate foes, the “realists”, remain in eclipse. Indeed, the most prominent Republican realist today is Robert Gates – who is serving as Secretary of Defense in the Obama Administration. Neoconservatives also remain extremely powerful in the media, and in mainstream US think-tanks like the Council on Foreign Relations.

Not merely that: in recent years the neoconservatives have extended their influence to Britain, through two new think-tanks, the Legatum Institute and the Henry Jackson Society (named after the movement’s political father-figure, Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson), and through a new, much-publicised magazine Standpoint. On present form, when the Republicans eventually come back to power – which could of course be as early as 2013 – their foreign policy will be heavily shaped by neoconservatives, and their allies in Europe will once again seek to drag America’s allies along in their wake. “In short,” as Vaisse writes, “neoconservatism has a future.”

Vaisse’s book is the best yet to appear on the neoconservatives. It is comprehensive, searching, highly critical, but also dispassionate in tone. Unlike many writers from either a liberal or a traditional conservative perspective, he is not concerned to “prove” that the neoconservatives are “not really liberals” or “not really conservatives”, and have “betrayed” one or other tradition.

Instead he traces the great complexity of neoconservatism’s history, and the highly contradictory positions its members have taken at different points. He identifies what he calls “the three ages of neoconservatism”, from its origins as a reaction against the multicultural Left of the 1960s – above all in domestic US affairs rather than foreign policy – through its time as a force for hardline policies against the Soviet Union in the 1970s and ’80s, to its ongoing incarnation after the end of the Cold War as a force advocating US global hegemony through a mixture of military might and the spread of “democracy”.

Over time, many figures who were originally considered neoconservative, like Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Samuel Huntingdon, Daniel Bell and Francis Fukuyama, have either explicitly turned against neoconservatism or have gone silent on the subject. Yet the movement has never lacked for new, younger recruits. It has, however, tended over time to become less diverse and more fanatical. Whether it has also become more Jewish is an interesting question. As Vaisse writes, while unconditionally pro-Israel it is by no means simply a Jewish movement and may eventually become more and more Indian, as members of the Indian lobby in the US join it to advocate a closer US-Indian alliance against Muslims and China and in support of free market “democracy”.

As Vaisse points out, over time, even core neoconservatives have adopted radically contradictory positions on a number of issues. This is above all true when it comes to the question of whether the US can and should make the promotion of democracy abroad a key part of its strategy, and seek alliances with other democracies.

In the 1970s and ’80s, this was something of which leading neoconservatives were extremely sceptical, arguing instead that the US needed to make alliances with authoritarian states to contain the menace of Communism, and insisting that President Jimmy Carter’s concern for human rights in places like Iran constituted dangerously unrealistic idealism which was weakening the US in the face of its enemies. In the 1990s and still more since 9/11, of course, the neoconservatives have however argued for democracy promotion as a central part of US strategy, and convinced Bush (probably sincerely) and Cheney and Rumsfeld (certainly insincerely) to echo this line.

This brings Vaisse to his concluding point. Neoconservatives, he argues, are above all American nationalists. This explains their staying power, because they are able to draw on much wider, older and deeper strains of nationalism which permeate US culture as a whole: both the civic nationalist belief in America’s mission to lead the rest of the world towards democracy and freedom, and the chauvinist nationalist celebration of America’s military might (and even brutality), and intense hostility to rivals and critics of the US. So deeply rooted are these sentiments in the US that any movement that can express them successfully – even in an extreme and bitter form – is assured of some sort of future. Vaisse might have made more of this extreme bitterness.

Neocons have an extraordinary capacity for national, cultural and political hatred. This was true not just during the cultural wars of the 1960s and during the Cold War, and not just since 9/11, when so many Americans shared in that emotion, but during the 1990s when America was unchallenged and seemingly at the very height of its wealth, power and security.

For an example of this aspect of neoconservatism, readers might wish (if they have the stomach) to dip into An End to Evil by Richard Perle and David Frum: a work of snarling contempt and hatred for almost every nation except the US, Israel and a very few unconditional dependencies. The danger here is not just that another attack like 9/11 might once more get many ordinary Americans to share in this hatred, but that the decline in the living standards of the US middle classes, coupled with the impact of immigration, may resemble previous travails of the lower middle classes in Europe in its ongoing effect on American nationalism.

But the neoconservatives suffer a very important structural weakness compared to their European equivalents: their alienation from the senior ranks of the US military. This reflects a gap in culture and experience – as is well known, the neoconservatives have shown no desire to risk their own lives in the wars that they have supported (which marks a contrast, by the way, with the first generation of neoconservatives, many of whose members had served in the Second World War).

It also reflects the fact that in recent years the US military has been forced to look up close and in detail at the limits on US military resources, and the extreme difficulty of following neoconservative strategies on the ground in many parts of the world. Thus in the last year of the Bush administration it was above all two successive chairmen of the US joint chiefs of staff – Admirals Fallon and Mullen – who acted to block a possible US or Israeli-US attack on Iran, as advocated by the neoconservatives. On military advice, the Bush administration also in the end backed away from confrontation with Russia over Georgia in 2008. This lack of military support for the neoconservatives’ militarist fantasies gives good hope that in the end the neoconservatives’ impact on the real world will be limited – as long as another 9/11 does not come along to deprive the American establishment and people of their collective wits.