When Time magazine interviewed Ian Wilmut after his team announced the cloning of Dolly the sheep in 1997, it remarked that “One doesn’t expect Dr Frankenstein to show up in a wool sweater, baggy parka, soft British accent and the face of a bank clerk.” It was one of many examples of how Frankenstein, supplemented by other myths both ancient (Faust) and modern (Brave New World), sets the context for media commentary on new developments that allow us to modify and perhaps to create living organisms. Even the “synthetic” microbe created by Craig Venter and his co-workers in 2010 was quickly dubbed “Frankenbug”, and reports dwelt on the perceived Faustian overtones of “playing God”. Some might say that, in the age of assisted conception and cloning, Mary Shelley’s Gothic novel is more relevant than ever. But that’s to put the case back-to-front: we shouldn’t be asking what Frankenstein has to tell us about reproductive technologies, but rather, how this 19th-century tale came to supply the journalistic shorthand that makes us fear them.

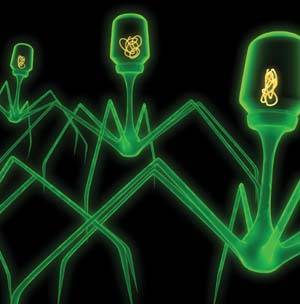

When Time magazine interviewed Ian Wilmut after his team announced the cloning of Dolly the sheep in 1997, it remarked that “One doesn’t expect Dr Frankenstein to show up in a wool sweater, baggy parka, soft British accent and the face of a bank clerk.” It was one of many examples of how Frankenstein, supplemented by other myths both ancient (Faust) and modern (Brave New World), sets the context for media commentary on new developments that allow us to modify and perhaps to create living organisms. Even the “synthetic” microbe created by Craig Venter and his co-workers in 2010 was quickly dubbed “Frankenbug”, and reports dwelt on the perceived Faustian overtones of “playing God”. Some might say that, in the age of assisted conception and cloning, Mary Shelley’s Gothic novel is more relevant than ever. But that’s to put the case back-to-front: we shouldn’t be asking what Frankenstein has to tell us about reproductive technologies, but rather, how this 19th-century tale came to supply the journalistic shorthand that makes us fear them.

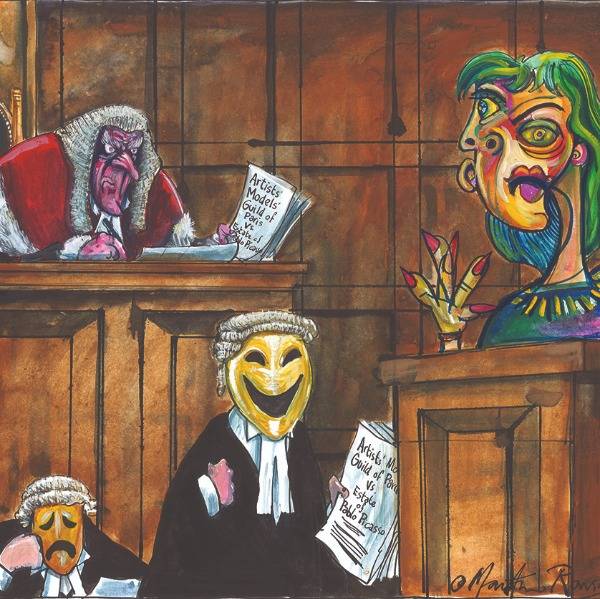

Robert Edwards, who was awarded the Nobel Prize last year for pioneering in vitro fertilisation (with the surgeon Patrick Steptoe), complained that the early reception of his work was conditioned by a public imagination that had been “dramatically doom-lit and gaudily coloured by science-fiction fantasies and visions – fantasies of horror and disaster, and visions of white-coated, heartless men, breeding and rearing embryos in the laboratory to bring forth Frankenstein genetic monsters.” Edwards’ frustration at this warped view of his efforts to alleviate infertility was understandable. But he failed to understand that these were not arbitrary prejudices, for the arrival of the test-tube baby elicited stereotypes accumulated from centuries of myths and legends about the artificial creation of human beings – what I call anthropoeia. Mary Shelley by no means invented the idea of making a man, even if her book provided one of the defining versions for the modern age.

Now that more than four million “test-tube” babies have been born worldwide, IVF seems largely socially normalised (at least beyond the Vatican, whose bioethics spokesperson pronounced Edwards’ Nobel “completely out of order”). But the same stock images are transferred on to every new reproductive technology, whether the production of “artificial sperm” from stem cells, human-animal hybrid embryos, or cloning. We will never have the honest and open debate that these undoubtedly contentious new technologies urgently need until we can recognise the influence of the mythic narratives.

Anthropoeia, be it Frankensteinian necro-surgery, Aldous Huxley’s babies in bottles, IVF or cloning, has always provoked outrage and disgust at first encounter, because it is often held to be the ultimate unnatural act. And to call something unnatural is not an act of taxonomy but a moral judgement. As historian Helmut Puff explains, “Un-enunciations condemn that which is expressed, declare it as dangerous, treacherous ground… Unnatural connotes a wretched state that ought to bring about the most vocal condemnation.”

Knee-jerk uses of the “Frankenstein” label now import a set of off-the-shelf prejudices that invite us to find something wicked and repugnant. Yet why does “unnaturalness” give us the shivers? Much of the disapproval stems from the theological tradition of natural law, which Thomas Aquinas formulated in the 13th century. Natural law plays out in a rationalistic yet teleological universe in which everything has a part to play, and all things have a “natural end” which, being ordained by God, is intrinsically good. The “natural” end of sex is procreation, since traditionally the latter required the former. Religious objections to IVF and other reproductive technologies that do not require sexual intercourse invoke this reasoning in reverse: the natural and therefore the sole proper beginning of procreation is sex – which is to say, not sex in the biological sense (sperm meets egg) but in the anatomical sense (this bit goes in here).

It is ultimately in its “unnaturalness” – its alleged contravention of nature – that reproductive technology is condemned by the Catholic Church; its censure by anti-science groups is merely a secularised version, in which God is replaced by a reified nature. And both involve a negative judgement about the moral character of technology itself, which is seen as intrinsically perverse and perverting.

One consequence is that the power of anthropoetic technologies has always been inflated. “Life is created in test tube”, one newspaper announced after Edwards and Steptoe reported the first in vitro fertilisation of a human egg in 1969. In the imagination of popular culture, it was not a microscopic ball of embryonic cells that the test-tube held, but a developing or even a full-term baby: IVF was immediately elided with the speculative technology called ectogenesis, in which gestation too happens in vitro.

This was no coincidence, for the methods of IVF fitted comfortably into ancient anthropoetic imagery. Alchemical symbolism abounds with pictures of people in glass jars, and arguably the first artificial people-making technology was the alchemical creation of a homunculus, often said to be done by fermenting human sperm in a sealed vessel.

Yet homunculus-making was rarely condemned merely on hubristic grounds. Rather, the medieval debate, informed by Plato and Aristotle, was about whether human art could compete with nature. Alchemical gold was suspect not because it was fake but because it was deemed inferior. In the case of the homunculus, this supposed shortcoming of human art had a particularly incendiary implication: the artificial being was considered to lack a soul. The impiety therefore hinged on the fact that either one was seen to be compelling God to give it one, or the homunculus would be free from original sin and not in need of Christ’s salvation.

Doubts about the artificial being’s soul are still with us, although more often expressed now in secular terms: the fabricated person is denied genuine humanity. He or she is thought to be soulless in the colloquial sense: lacking love, warmth, human feeling. In a poll conducted for Life in the early days of IVF research, 39 per cent of women and 45 per cent of men doubted that an “in vitro child would feel love for family”. (Note that it is the sensibilities of the child, not of the parents, that are impaired.) A protest note placed on the car of a Californian fertility doctor when he first began offering an IVF service articulated the popular view more plainly: “Test tube babies have no souls.” This same failing is now imputed to human clones: the very word carries connotations of spiritual vacancy. “Soul” has become a kind of watermark of humanity, a defence against the awful thought that we could be manufactured.

Although anthropoeia has long been seen as a Faustian enterprise – an act of hubris liable to doom the maker – the creation of a homunculus in Goethe’s Faust was more ambiguous. This deed is done not by the alchemist himself but by his assistant Wagner, and the “dapper charming lad” who results is far from baleful: a super-being with magical powers, but imprisoned in his glass vessel unless he can be reborn in human flesh. Wagner makes him not to mock or challenge God but so that procreation need no longer require something as undignified as sex. He is highly sympathetic and intelligent, a personification of the liberated human intellect.

But any possibility that the artificial being might be more-than-human was eclipsed by Frankenstein. By making Victor a “modern Prometheus”, Mary Shelley ensured that hubris was placed at the centre of her fable; because hers was a world in which God no longer intervened directly, the creature itself was called upon to exact the retribution that Faustian tradition demanded. What’s more, it was no longer sufficient for the artificial being to be conjured up by occult alchemical forces. Mary Shelley was cagey about precisely how Victor did it, but there’s no doubt that it involved some form of science, most probably a combination of anatomical assembly and the “galvanic” physiology then in vogue, which built on the theory of Italian scientist Luigi Galvani that living beings were animated by an “electrical fluid” produced in the brain. Galvani’s experiments using electricity to set frog limbs twitching, and particularly those of his nephew Luigi Aldini, who induced movement in the corpse of a recently hanged criminal, were thought to imply that one could travel either way across the boundary between life and death.

What Frankenstein means to us now has less to do with Shelley’s story than with what became of it in popular culture. Even Shelley herself revised her book to accede to the crude moralising about “presumption” in the stage versions that began to appear within five years of publication. But the most significant alteration introduced in these retellings, culminating in James Whale’s definitive 1931 movie with Boris Karloff, was that the eloquent creature became a clumsy, inarticulate brute: an insistence that the artificial being must be subhuman, far removed from the sparky sprite of Goethe’s homunculus. In part, this re-imagining of Frankenstein’s monster drew on the people-making Jewish legend of the golem, but Whale’s flat-headed, bolt-necked creature also alludes to a modern incarnation of the artificial being: the robot.

The original robots of Karel Capek’s 1921 play R.U.R. were synthetic people: made not of metal but of flesh and blood, their limbs and organs grown in factories and assembled like the components of Henry Ford’s automobiles. And that was Capek’s seminal and prescient contribution to anthropoetic mythology, for he realised that the art of making people would leave the alchemist’s secluded laboratory and enter into mass production. “Making artificial people is an industrial secret,” says Harry Domin, director general of the robot firm R.U.R.

It then remained only for Aldous Huxley to show how this industrial anthropoeia would really be done: not by Frankenstein-like assembly but by growing babies in bottles, in the Hatcheries of Brave New World (1932). Here Huxley was merely extrapolating the technology that was being promoted by the biologists of the time, especially his brother Julian and their friend JBS Haldane. In his 1924 book Daedalus; or, Science and the Future, Haldane portrayed a world in which ectogenesis had liberated women from the oppression of child-bearing, a vision welcomed by many liberals and feminists. At the same time, ectogenesis made procreation amenable to state control, so that it might be used for eugenic purposes to ensure that over-breeding in the “bad” gene pool should not lead to physical and moral degeneration in the population.

These are now our stereotypical points of reference for discussions about reproductive technology. The “artificial” being will be monstrous and soulless. And like Capek’s robots, it threatens to destroy us and supplant humankind – Frankenstein refused to make for his creature the “bride” he coveted, for fear that “a race of devils would be propagated upon the earth who might make the very existence of the species of man a condition precarious and full of terror.”

Then in the 20th century anthropoeia was re-imagined as an industrialised process that would lead to social engineering, gender annihilation (male or female, take your pick) and the creation of a master race. This is just one of the ways in which anthropoeia becomes a lens that refracts the prevailing social mores and anxieties: Brave New World was a fable appropriate to a time when totalitarian ideologies were haunting Europe. To think that it applies today, when the danger is not that IVF and cloning (say) will be abused by dictators but that they will be abused by the free market, is not just to miss the point but to abrogate responsibility (as the United States has) for their responsible regulation.

The problem is not that we have myths about anthropoeia, but that we misunderstand (wilfully or otherwise) the role that myths serve. They are a cathartic expression of human experience, often encoding our deepest hopes and fears, and yes, they are repositories of accumulated wisdom. Frankly, they can also be entertaining, as Danny Boyle and co. will doubtless illustrate. But they are not deterministic predictions about the future, nor even warnings about what lies in store if we do not watch our step (do we need to be reminded not to have sex with our parents?). It is all too easy for self-appointed moralists who warn that reproductive technologies will lead to Frankenstein monsters and Brave New Worlds – whether they are the Daily Mail, the religiously motivated bioethicists who determined George W Bush’s biomedical policies, or anti-biotechnology crusaders – to tap into familiar, legendary nightmares that foreclose a grown-up debate about how, why and when to regulate the technical possibilities (as we must). There is plenty to debate, and the wisest course is neither obvious nor easily negotiated. But until we can recognize the origins of our preconceptions, and distinguish mythical fears from real and present dangers, we shall have little prospect of getting it right.

Philip Ball's new book, Unnatural: The Heretical Act of Making People, is published by Random House in February

This piece is from the January/February 2011 issue of New Humanist. subscribe