As ethical dilemmas go, this is one of the milder questions raised by Visceral, an exhibition which gleefully disregards strictures against Frankensteinian manipulations of nature, delving instead into art which uses stem cells, tissue cultures, live insects and, of course, human blood as materials. The exhibition consists of two floors of peculiar artefacts in the glass-walled expanse of the Science Gallery, and at its centre is an entire laboratory (no public access allowed – “YOU ARE A BIOHAZARD”, reads the sign), where artworks are prepared, changed and developed – I watch as two young women in lab coats and full make-up hold up and closely examine a bag of red, liquid human tissue. In a niche at the front of the laboratory, doll-shaped slivers of matter are spinning in a Rotary Cell Culture System, presumably in the act of creation. You could be in a scene from JG Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition, where the medical and artistic are conflated in strange and often coldly alluring ways.

What we have here is an impressively fearless, enjoyably amoral bridging over the long-in-the-tooth “Two Cultures” divide, marked by a refusal to take any sort of clear ethical position. SymbioticA is run by Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr, who give artists “access to resources” at the School of Anatomy and Human Biology at the University of Western Australia in Perth, the most remote big city in the world, which, as more than one of the artists point out, is a good place to hide. The laboratory teaches artists the basics of “DNA extraction, genetic engineering, selective breeding, plant and animal tissue culture and basic engineering techniques” and runs “intensive one to five day workshops where participants learn how to engineer life, from the molecular to the tissue level”. That even, Ballardian tone to the writing is common to everything in Visceral; the possibility that there might be ethical dilemmas here is sidestepped in what is undoubtedly a refreshing manner, with a total lack of the didactic signage and hand-holding that even the simplest art exhibitions have today. From dog-breeding to flower-arranging, we manipulate nature for our aesthetic jollies every day – why not do the same with biotech?

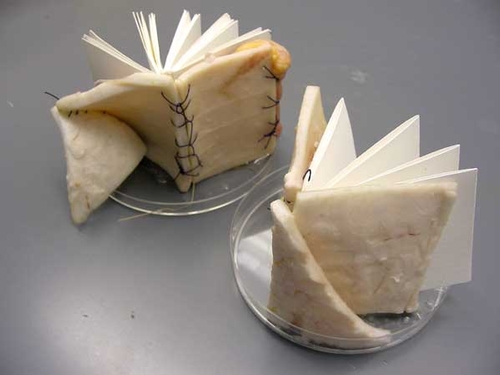

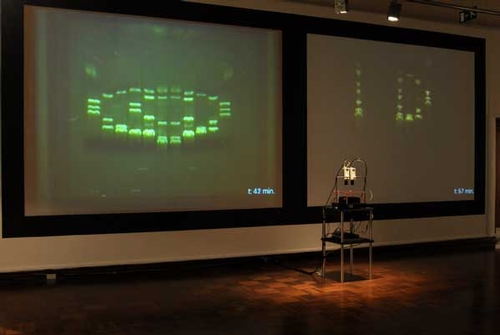

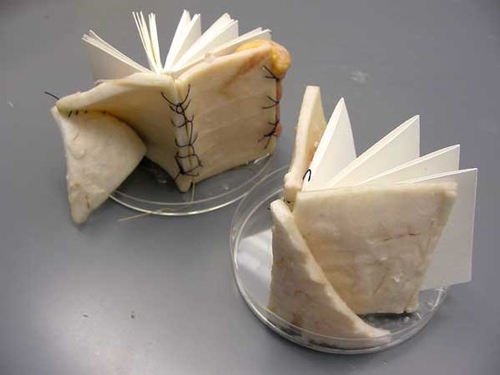

There’s only one piece here that counts as a scientific as much as artistic experiment – “Silent Barrage” by the group Neurotica, where a collection of robots spatially mapped onto and linked into a laboratory in Georgia somehow enable research into epilepsy, and it’s also by a long chalk the most difficult – if sublime, in its scale and implications – work for the layman to attempt to understand. The other artworks entail not so much scientific experiments as the use of biotech to create uncanny, haunting art objects, courting disturbing but often impenetrable associations and images, unexpected correspondences of biology and psychology rather than straightforward links. A recurrent idea is using biology as technology, as in Boo Chapple’s “Transjuicer”, a “cow bone audio speaker” which “transduces electromagnetic waveforms – in this case bone songs and cow songs – with nanosonic vibrations”. It’s unfinished when I visit, catching only the artist taking a massive, gory cow bone out of her bag, surrounded by “totem poles” of books and scientific ephemera. Similarly, Tagny Duff’s “Cryobook Archives” entails surplus surgical material from elective surgery in Belfast, donated via a consent form, “for the purpose of art”, which is then shaped into “books” – little booklets with covers made from thin, rotting cheese, placed in a wood-clad, mock-antiquarian freezer. Others are more Grand Guignol – Alicia King’s “The Vision Splendid” is an assemblage of tissue in a bag as part of a tableau of living, dead and “undead” matter, arranged with an aesthete’s eye.

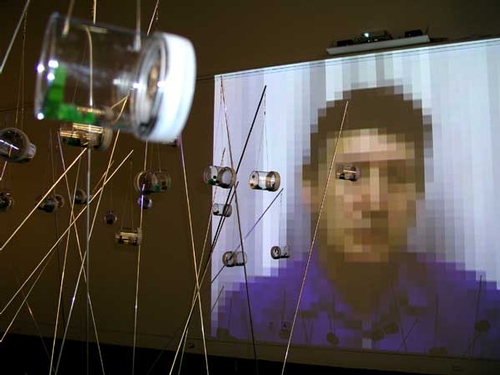

Like a lot of the “matter” in the exhibition, this undead tissue is described as “semi-living”, often stem cells in the grey area where the question of whether something counts as “life” becomes increasingly unclear. She describes it as “a living relic”, that this “product of contemporary biological technologies acts as the ultimate ‘miracle’”. Yet the provenance of all this couldn’t be more matter-of-fact – “the living tissue growing in the glass bioreactor originates from an anonymous female patient...purchased through the American Type Culture Collection online catalogue, which itemises over 4000 human, animal and plant cell lines available to order.” Apart from those of us wandering around the Gallery, the only straightforwardly “living” creatures in the exhibition are in Nigel Helyer’s “Host”, where a hundred or so crickets in elegant jars – ordered from China, where crickets are collected – listen to a lecture on insect sex lives. On one side is footage of this lecture, pixellated as an approximation to insect vision, on the other the image (and amplified sound) of electrical activity in the aural nerve of crickets listening to the lecture. It’s an elaborate and ornate joke on our inability to imagine the “sex life” – the very term is absurd – of this entirely common creature.

Biotechnology here is something akin to magic, an indeterminate, baffling thing which is used as some sort of icon or talisman. Catts and Zurr’s “Semi-Living Worry Dolls” take that idea and runs with it. Based on the “worry dolls” of Guatemala, little toys to tell your troubles to, they’re doll-shaped strips of engineered tissue, using techniques borrowed from human organ replacement. They describe the dolls as “a device to tap into anxieties” – a little microphone records the problems you tell to the dolls, and they claim to have had “200,000 worries collected” since the dolls were first created in 2000. They’ve been told all manner of intimate things, according to the artists, although they note that “Ireland is at a time when it has quite a few interesting worries”, hoping that those caught up in the still ongoing financial crash might have something to say to these creatures. It’s maybe the only time that any political implications are explicitly acknowledged in the show.

Catts and Zurr cite a 1927 short story by the evolutionary biologist, eugenicist, humanist (and brother of Aldous) Julian Huxley called “The Tissue Culture King”, as a way of explaining what they do. In this HG Wellsian tale, a biologist is taken prisoner by the “king” of an African village, and in order to save himself, he uses his technologies as magic, mysticism – as a form of religion, in terms strikingly redolent of SymbioticA’s work. With a petri dish and a microscope, he explains to the “natives” that “the blood was composed of little people of various sorts, each with their own lives, and that to spy upon them thus gave us new powers over them. The elders were more or less impressed. At any rate the sight of these thousands of corpuscles where they could see nothing before made them think, made them realize that the white man had power which might make him a desirable servant.”

This is what Visceral is really about – the contention that our interpretations, desires and fears are all too able to run ahead of our ability to comprehend the multiplying complexities of biological science. Huxley’s story charts how easily the seemingly baffling biotechnologies can be given non-scientific “meanings”, even religious ones. “He next applied himself diligently to a study of their religion and found that it was built round various main motifs. Of these, the central one was the belief in the divinity and tremendous importance of the Priest-King. The second was a form of ancestor-worship. The third was an animal cult, in particular of the more grotesque species of the African fauna. The fourth was sex, con variazioni. (He) reflected on these facts. Tissue culture; experimental embryology; endocrine treatment; artificial parthenogenesis. He laughed and said to himself: ‘Well, at least I can try, and it ought to be amusing.’” He calls his church/laboratory the “Institute of Religious Tissue Culture”.

SymbioticA are planning a big funeral at the end of the exhibition as the tissue is destroyed; last rites to be watched by those who are unclear whether what is being laid to rest even counts as “life”. Visceral uses the material of our astonishing power over matter, but as a means to show how ill-equipped we are to understand it; it’s fundamentally sceptical, even fatalistic, about human potential. It’s science as art, but also art as nihilism.