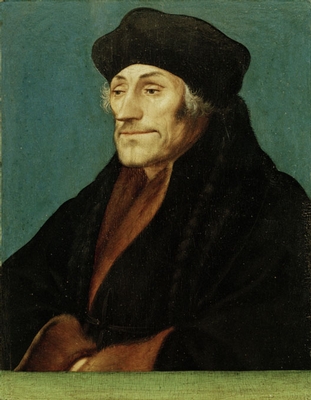

These institutions were already beginning to register the influence of Northern humanism, a movement that sought to establish a new synthesis of the values inscribed in ancient Greek and Roman literature and those of Christianity, and that counted Erasmus as its prince. The humanist idea amounted to a programme for educational, theological and religious reform, and in The Praise of Folly – which Erasmus composed over seven days in England in the house of his “sweetest” friend, Sir Thomas More (the book’s title in Greek, Morias Enkomion translates as The Praise of More) – we find the period’s most condensed and ironic example of this radical attempt to harmonise the heuristic claims of rational philosophical enquiry with those of revealed religion. The Folly fast became the most famous secular book of the century (running through 36 editions in Erasmus’s lifetime alone); it provoked enormous controversy; and to contemporary readers it must have seemed, to borrow from Peter Ackroyd, “as if the whole structure of the late medieval world was being shaken.”

One of the most shocking things about the book was its style.The narrative, which is prefaced by a dedicatory epistle to More (my readers will “accuse me of ripping everything to shreds,” says Erasmus), takes the form of a single speech, delivered by the figure of Folly. This might not seem an astonishing move. But by conflating the subject of the speech with its speaker, Erasmus had roused from its thousand-year slumber the genre of the paradoxical encomium, which had classical antecedents in the work of Aristophanes and Lucian, and whose biting and ludic mode was considered indecorous for moderate Christians. The truly remarkable thing about Erasmus’s use of the genre, however, was that he had chosen a subject that made the speaker of his encomium both self-affirming and self-negating. The effect is radically destabilising: Folly persuades us that wisdom is foolish, but if she is truly a fool can anything she says be wise? And if wisdom is foolish, isn’t it deserving of praise? Erasmus upsets the reader’s hermeneutic equilibrium, leaving a text in which meanings are constantly on the move.

Folly begins the religious section of her speech by celebrating the virtues of illusion, for which she alone is responsible. Consider all the Christians who seek “comfort in soothing self-delusions about fictitious pardons for their sins”, she says. Could they believe they were going to be pardoned without the illusion provided by Folly? No. How miserable their lives would be! And what if a philosopher were to convince believers that religion is nothing but nonsense? Would they be happy in that knowledge? Of course not, she says: “to lack all wisdom is so very agreeable that mortals will pray to be delivered from anything rather than from folly.”

Provocative as this is, it is playfully and ironically achieved: we are never sure what precisely is being argued. Yet as Folly’s narrative on religious malpractice develops, the atmosphere of the book, once thick with irony, begins to clear. (The genre changes, like weather.) As it does so, the Folly persona fades and flickers, and we keep catching glimpses of “Erasmus”. “He” scorns “great and ‘illuminated’ theologians” for their obsession with the Trinity; for the religious authority they have arrogated to themselves (no one can be “a Christian unless he has the vote of these bachelors of divinity”); for their use of the “thunderbolt” label of heretic in order “to terrify anyone to whom they are not very favourably inclined”. And “he” sarcastically asks what would happen to all the “wonders” of Catholicism – the ceremonial pomp, the pointless titles, the sale of indulgences, the violence – were the religion to adopt the ways of Christ.

Erasmus, of course, recognises the generic slip, and has Folly explain that she will change tack, lest she should seem “to be composing a satire rather than delivering an encomium.” But the satire – irreligious, anti-clerical – has already occurred; the reader has already been exposed to a raucous volley of demystification, and that demystification continues as we encounter a statement of flat-out anti-theism. Here, Christians are dismissed as fools who “throw away their possessions, ignore injuries, allow themselves to be deceived, make no distinction between friend and foe, shudder at the thought of pleasure, find satisfaction in fasts, vigils, tears, and labors, shrink from life, desire death above all else.” It is as if Christopher Hitchens has stepped on to the page.

The comparatively radical positions that are adumbrated in The Praise of Folly should not unthinkingly be taken to be representative of Erasmus’s own beliefs, but by placing them in print he gave them a life of their own. Accordingly, he fretted over the use to which vernacular translations of the Folly might be put, and Thomas More, who thought of Erasmus as his “derlynge”, wrote that if confronted with any such editions, he would burn them with his own hands, “rather than folk would . . . take any harm of them, seeing them likely in these days to do.”

More, of course, was referring to the threat of Martin Luther and the Reformation. A saying of the time had it that Luther merely hatched the egg that Erasmus had laid, and the “rational”, accommodating and non-theological faith advocated by Erasmus clearly had some Protestant appeal. Furthermore, the early correspondence between the two men does contain signs of mutual admiration. Yet they would come to have profound and public disagreements, in print, about the nature of free will, and about the relationship between reason and revelation. For Erasmus, whose first public attack on Luther, De libero arbitrio, appeared in 1524, the two could, should, work in harmony, but he remained uneasy about the directions that rational enquiry, when it met with religion, might take.

Erasmus would have been dismayed, for each of these developments showed systems of religious belief that were giving ground to reason, were being eroded by rationalism. Luther would have shared his distress. But he would not have been surprised. For him, the confluence of religion and reason was bound to lead to either atheism or heresy. As he wrote in the De servo arbitrio – his response to Erasmus’s De libero arbitrio – in 1525: “if you respect and follow the judgement of human reason, you are bound to say either that there is no God or that God is unjust.” Yet Erasmus remained convinced that it was possible to unite the rational claims of classical philosophy with the divine claims of Christianity, and possible to do so without outraging either. The rational, secular, “heretical” channels into which his ideas would flow suggest that Luther might not have been wrong.