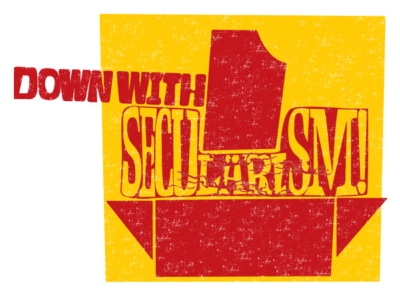

It compromises democracy, it promotes and rewards hypocrisy and doublethink, it reflects a crippling failure of imagination on the part of its proponents and it’s founded on principles that are cynical, unempathetic and deeply un-humanist. It’s called secularism, and I think it stinks.

It compromises democracy, it promotes and rewards hypocrisy and doublethink, it reflects a crippling failure of imagination on the part of its proponents and it’s founded on principles that are cynical, unempathetic and deeply un-humanist. It’s called secularism, and I think it stinks.

You may disagree.

In which case, you may wish to say so. And this is where we run up face-first against the tenets of common-or-garden modern liberalism.

The liberal lawyer David Allen Green recently articulated this position perfectly in 140 characters or less: “If you don’t want to have abortion, don’t have one; not want gay marriage, don’t have one; but you have no right imposing views on others.”

Which is exactly what I mean by a failure of imagination.

Every citizen has every right to impose his or her views on others – and every other citizen has an equal right to tell him or her to take a running jump.

The preposterous Bradford MP George Galloway recently resorted to the liberal get-out clause in the same vein, turning Green’s dictum through 180 degrees and insisting – a propos his conversion (or otherwise) to Islam – that religion “is a private matter”.

Not so. If my MP believes, in his heart of hearts, that four plus four makes nine, then I want to know about it. It is very much my business, just as it is if my MP harbours a belief in racial supremacy or is secretly convinced that the only way to secure lasting global peace is to stage a land invasion of China. Just as it is if my MP believes in God.

I don’t want a Christian – or a Muslim, or a Hindu, or a Scientologist – as my MP. I would like to see a House of Commons entirely empty of deists and theists. But this isn’t because I’m opposed to religion; it’s because I’m opposed to people getting things wrong.

The basic premise of secularism is that religion should be kept out of politics (there’s more to it than that, I know, but that will do us for now). My premise is that people who get things wrong should be kept out of politics.

How is that to be done? Why, by not voting for them, of course. Not by erecting self-serving and undemocratic Chinese walls between “church” and “state”, “religion” and “politics”.

Apart from anything else, secularism is a breathtakingly patronising doctrine.

“Yes, yes, believe all that guff if you like,” the secularist says to the Christian, “but please, take it away and play with it elsewhere – while we get on with the grown-up business of running the country.”

“You can come in and help us, if you like,” he might add, “as long as you pretend that you think pretty much like we do, and don’t give us any twaddle about God telling you what to do.”

Secularists talk as though rationalism and social liberalism are fundamental, generally accepted truths (“You know it, I know it. Let’s move on.”). This is by no means the case. People believe some right old guff. In fact, they’ll believe pretty much any old guff (for them, as the Tom Waits song says, “Everything You Can Think Of Is True”). And I’m afraid that this is not something that we can brush aside with a snigger and a dismissive gesture; as long as people believe in guff, then guff has a place in our Parliament and our legislature.

Let’s take another look at that liberal phobia about “imposing your views on others” (and let’s leave aside that “imposing”: apart from being freighted with the symbolism of jackbootery, it’s not really important in this argument – whether and how things are “imposed” is a question of government practice, not policy).

Perhaps the argument here is that a gay marriage or an abortion, say, is in some sense a personal matter, and nobody else’s business. If so, it’s an argument that crumbles as soon as you spin it around and take a look at it from the other side. If I believe that human life is sacred, then an abortion is essentially a murder. A woman has no more right to terminate her foetus than a mother has a right to strangle her three-year-old son. And a person who believes this has a moral obligation to prevent it wherever possible. The same goes for a person who believes that human society is being irreparably damaged by buggery and opiates (or whatever) – and the same goes, too, for a government.

It is deeply dismaying that so many liberals struggle with this basic empathetic step. Anti-abortion activists and their ilk are not (necessarily) evil or wicked or heartless. They’re just incorrect. They have made an error in reasoning. They have got their sums wrong. That’s all.

Of course, support for secularism doesn’t come only from atheists, humanists and others of their otherwise right-thinking ilk. A recent survey of Christians by IPSOS MORI found “overwhelming support for religion being a private, not public, matter”. Three quarters of those who self-identified as Christian in the 2011 census “strongly agree” or “tend to agree” that religion should not have special influence on public policy. A smoking gun for the secularists? Well, let’s think about what this stat means.

Does it mean, for a start, that UK Christians don’t want leaders who share their views? Of course not. Everyone wants that: we all, of course, think that our views are the right ones – and we all want our MPs to be right, right?

So if the Prime Minister thinks I’m right about everything (which, of course, I am), does that constitute “special influence”? I should damn well hope so. He’s not the Prime Minister for nothing. People who believe that an abortion is a sin (or, contrarily, who believe that you should be able to buy one at Sainsbury’s with your Nectar points) want a PM who believes the same – and who, crucially, acts on this belief. This latter point is fundamental. Who wants a hypocrite for a Prime Minister?

Hard as it is to imagine, it seems that the Christians surveyed by IPSOS MORI may not have thought this all the way through.

The Princeton Professor of Religion Jeffrey Stout has pointed out that “some people in liberal societies hold religious views which will influence significantly the contribution they wish to make to public debates... But these [people] recognise quite pragmatically that their religious motivations and justifications are not shared by everyone else. So they present their views in ways which can be agreed with by people who do not share their religious perspective.” (The quotation is from Graeme Smith’s Short History of Secularism.)

That is, they practise hypocrisy and cant. And the secularist lobby is quite happy for them to do so.

Imagine that the Health Secretary stood up in the Commons and announced plans for a rejig of the NHS based on the principles of Christian faith-healing. I would think that his statement was deeply troubling. Not because it was religious, but because it was idiotic.

There are many kinds of idiocy, of which religion is only one. None of them ought to be excluded by law from having a say in the running of the country. All of them, however, should be challenged at every turn by the real powerhouse behind any true democracy: argument.

If I were to be the only atheist in a country otherwise full of Christians, I would want and expect the government to be run on Christian principles. I wouldn’t like it, of course – but that’s democracy.

I would also want to start an argument. I’d want to start lots of arguments.