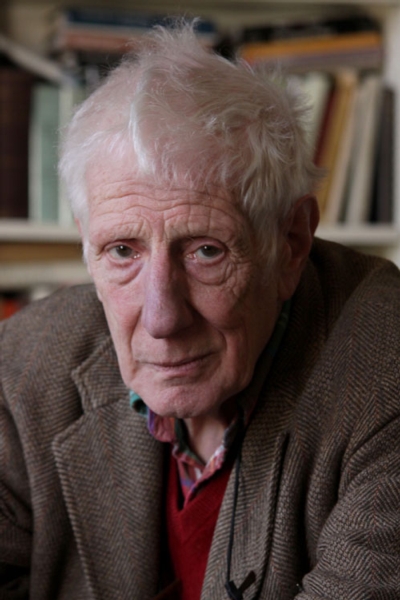

Well, perhaps. But the sheer range of Miller’s accomplishments seems to contradict him. Whether on the page (in books like Censorship and the Limits of Personal Freedom; Freud; and Laughing Matters or numerous articles and reviews for the New York Review of Books and the New Yorker); on the stage (as a comic in Beyond the Fringe or a much feted opera director with his Rigoletto or Mikado); on the screen (with his fine adaptation of Alice in Wonderland); or on the telly (by way of the 13-part series, The Body in Question, or by way of Atheism: A Rough History of Disbelief), and without bringing in his neuropsychological research or his sculpture and painting, Miller’s CV is stunningly wide ranging. If Miller is a grasshopper then he is surely one of the brainiest members of the Caelifera family, possessed of a daunting insect intelligence that puts the rest if us benighted bipeds to shame.

Miller’s impatience with the polymath cliché is characteristic. He is well known to dislike exaggeration and hate the heroic, believing that most of what is interesting lies in the negligible and the overlooked, and that it is the job of art to direct our attention toward the neglected and forsaken everydayness of things. Yet his fearsome intellect and not-much-hidden disdain for those whose ideas he does not respect – he once famously dubbed the influential French philosopher Michel Foucault “a poltroon” – can give him a hint of haughteur, even a soupçon of self-regard, as if the too-easily-reached-for polymath label somehow underestimates the true scale of his achievements, and the work that went in to producing them. Modestly, false or otherwise, isn’t really Miller’s mode, but then he has very little to be modest about.

Given this I wonder if there is anything he can’t do, or hasn’t done, that he would still like to do. He is, after all, only 78. “In a way I wish I had stayed doing medicine and taken up what I was interested in, which was what we call neuropsychology: looking at what brain damage does to various capabilities.” Miller famously studied neurology alongside Oliver Sacks, and you get the feeling he might rather have liked to tread the same line between science and literature. “I would like to have done that, but I got pulled sideways into the theatre.”

That was in 1962, three years after Miller qualified as a physician, and the anxiety about being pulled away from academic study seems never to have left him. Is there nothing less lofty or studiedly intellectual he’d like to do? “For the last 30 years I have been involved in making some sort of things that you might call art: sculpture (well not sculpture: assemblages), and abstract painting. And photography. I’ve always been doing that, half-heartedly. No, not half-heartedly exactly. Often quite enthusiastically. Occasionally I have held exhibitions.”

What, then, does he do to relax? He dismisses as journalistic puff the rumour that he spends 90 per cent of his spare time reading, then reveals that it is to all intents and purposes true: “I do read a lot, although as I get older I get less and less good at remembering what I’ve read. I read history of science, and history of thought, and history of ideas – that sort of work has always preoccupied me. At the moment I’m reading a huge book of nearly 700 pages on the history of the Enlightenment. It’s overwhelmingly learned.”

All this productivity, all this study, you sometimes get the feeling that Miller is trying to compensate for a deficiency he doesn’t have. But in fact he believes that the point of this lifetime learning is continually finding out how much he doesn’t know. It is a perfectly rational position, but one that seems to haunt him. Having absorbed a new history of the Enlightenment, he can now only see the deficiencies of his impressive series on the history of disbelief: “It is,” he tells me, “a vast and tremendously complicated topic, and for someone of whom it is claimed knows a lot ... I’m more disconcerted by how much I don’t know.”

One does wonder what he’s like to live with. I ask him. “I don’t know,” he says (bemused by this turn to the personal), “you’d have to ask my family. I think they often find me quite discontented and grumpy about what I have failed to do, and I get depressed by how I’m not doing what I ought to be doing, and I think they find that quite difficult. My wife does, I know.”

The sense that he is not doing what he ought to be doing, or not finishing what he ought to be finishing, Miller numbers among his greatest shortcomings. It is rather reassuring, to hear this consummately accomplished man worrying about what he hasn’t accomplished, worrying about “Starting things and not finishing them. There are lots of things I had set out to write and then got blocked halfway through.” While were on the subject any other, more personal, deficiencies? “I don’t think I make sufficient contact with my friends. As I get older I retreat more and more into solitude.”

It all sounds rather gloomy: shortcomings, retreat, remorse. From an individual of such extraordinary achievements, these feelings might be refreshing, but do they betray a strain of irrationality in this profoundly rational mind? He is, for example, a smoker (he was once caught by someone I know sneaking out of hospital to furnish himself with 10 Silk Cut), a habit from which he claims to derive no pleasure: “I’m rather ashamed of doing it and my family don’t like me doing it and I always have to go outside to smoke. I wish I hadn’t smoked. I mean, I’m old enough not to care too much because I’m going to die anyway, not too far away. I find myself doing it because I’ve been doing it a long time and it’s become something I do and hate doing but nevertheless find it very hard to resist. It doesn’t give me any pleasure.” And his attitude to that most rational and civilised of activities, drinking, is almost hysterically hostile: “I don’t drink anything at all. I can’t bear alcohol. I just don’t like the taste. It just is rather silly. I don’t like wine. I don’t understand why people go on with such pedantry about the different varieties of wine. I don’t think I’ve drunk more than two bottles of wine in my life. And beer for me is just the effluent of a cowshed.”

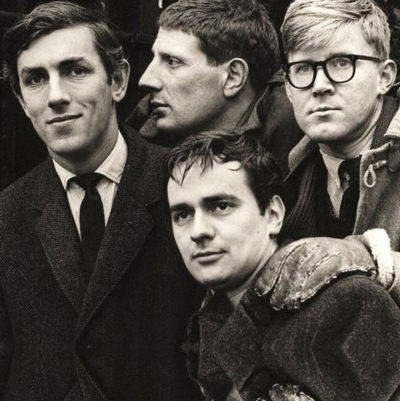

Yet behind the disgruntled demeanour – and notwithstanding the fact that he’s clearly utterly wrong about booze – lies a reminder of Miller’s great capacity for levity. Let us not forget that he once performed with Alan Bennett, Peter Cooke and Dudley Moore. Whatever he is doing he takes enormous pleasure in the pleasures of language, and the less obvious pleasures of other things besides. “I am,” he once said to Clive James, “a stationary freak. I really do buy unnecessary amounts of it, and I have cupboards filled with all different types. I love graph papers. There are these wonderful subtly tinted graph papers you can get. I can go on at great length about different denominations of ball-point pens, and fibre-tips ... They’re like individual sweets and candies: I’ll have that, I’ll have that, and that and that. There’s a feeling that it’s going to actually produce a huge Niagara of creativity. But in fact all that happens is you just get piles of pens and no writing.”

Every writer will know the feeling. But in Miller’s case the creativity really has come in waterfalls: Books have been written, films have been wrapped, sculpture sculpted, documentaries broadcast, plays and operas staged. Though his range is vast the scale is determinedly human; he focuses on the peculiarities and minute textures of being our species. Behind the apparent diversity of subject matter is a unified theme, as a whole they add up to a coherent neuropsychology of everyday life.

Miller has never had anything “that you could possibly call a religious belief, or even feeling”, for him religion is “alien, uncongenial and – to be frank – unintelligible”. He looks on life with something of the dispassionate eye of the surgeon, but also with the undimmed fascination of the enthusiast. As flawed as it all evidently is, he really loves life. “We have short lives,” he told Laurie Taylor in a television interview, “almost all of which are frustrating, which end in death. We go through life being thwarted and frustrated, every now and then, we’re gratified by carrying off something which is in fact what we wanted to do.

What is heroic is the fact of a conscious creature thrown into existence in the knowledge that he or she will be thrown out of it again. There isn’t anything else, but that’s quite enough to be going on with thank you very much.”