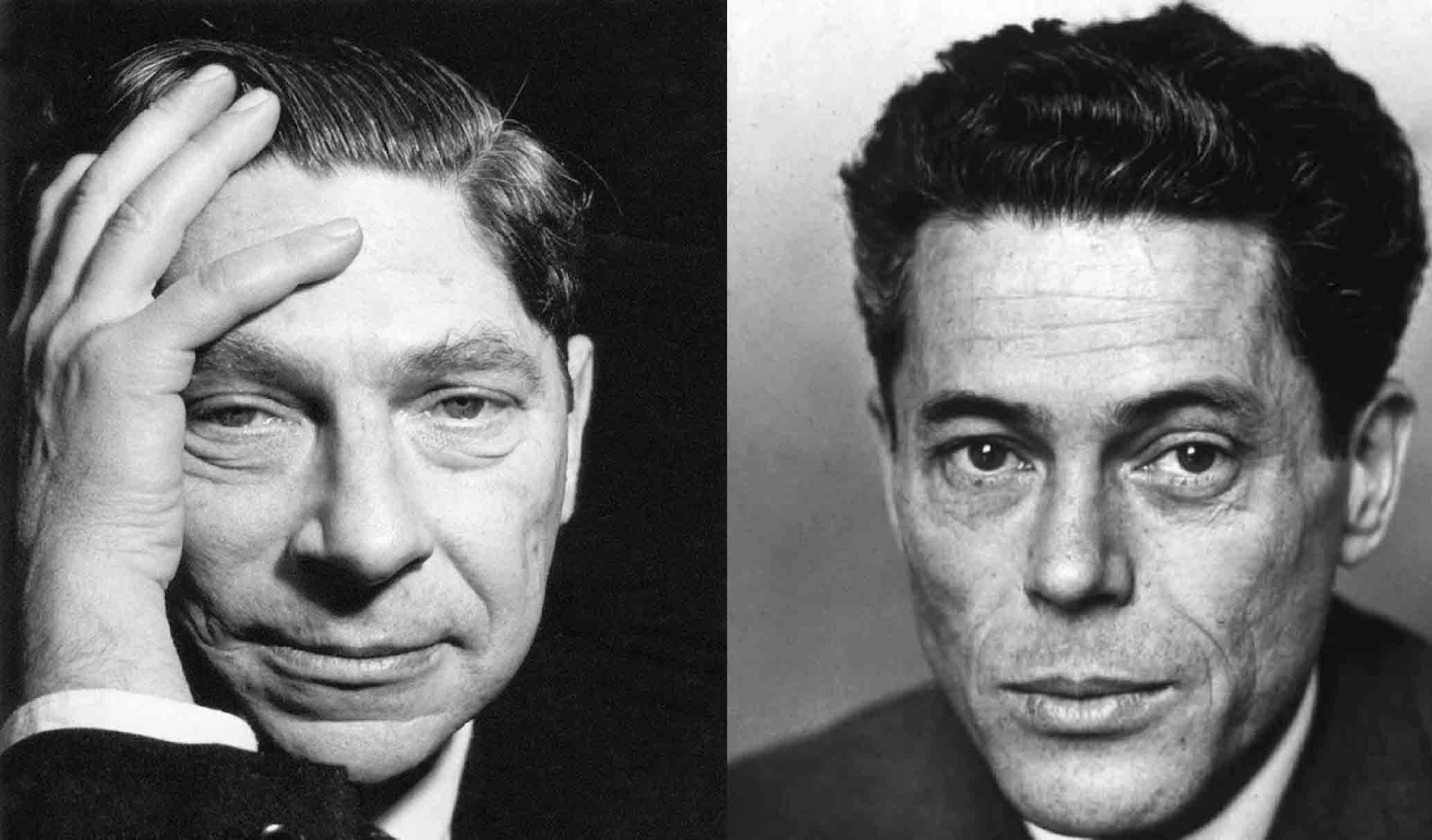

In September 1969, I was at a conference in Stockholm whose subject was The Place of Values in a World of Facts. Many famous people were present and during one coffee break I witnessed an exchange between two great intellectuals of the mid-20th century: the well known British-based writer Arthur Koestler and French Nobel-winning biologist Jacques Monod.

Here is how I remember the conversation.

“Arthur, is it true what I hear that you are interested in extra-sensory perception and such things? I find this worrying.”

“Yes, Jacques, I do find ESP very interesting and worthy of investigation.”

There might have been a bit more discussion about this subject between the two men, which clearly disturbed Monod, and then he said:

“Arthur, don’t you remember? We were both in the Party!” meaning therefore that had they had both previously professed atheism.

Koestler gave a somewhat reluctant nod of acknowledgement Then, Monod blurted out: “If you go on like this Arthur, before long you’ll be talking about [Monod struggled to get the word out]…God!”

Koestler, who had a cigarette in his hand, drew on it with masterful pausing for effect, and then said, “Not necessarily so, Jacques.”

I have never forgotten this short conversation and the import of it has grown on me in recent years. That the two men addressed each other by their first names suggested that they had known each other before and perhaps had corresponded. Koestler was at that time 64 and Monod 59. It was Monod who said both men had earlier membership in the Communist Party in common. But whereas in Koestler’s case this was common knowledge following his brilliant exposé of the brutalities of Stalinism in the much acclaimed novel Darkness at Noon (1941), I can find no reference to Monod’s earlier membership in the Party, although his left-wing views were well-known, causing a stir in 1968 when, as a senior French academic, he had come out in support of the student demonstrations that were rocking France and other countries of Europe.

Koestler not only left the Party but moved to the right, even working for the CIA for a while. He then turned his attention to the history and philosophy of science, writing a large trilogy on the subject and showing an extraordinary ability to grasp scientific concepts across a broad spectrum, with the important exception of biology. Throughout Koestler shows a bias against science, which he saw as destroying religious faith and diminishing man’s humanity. In the third book The Ghost in the Machine (1967) Koestler writes: “One cannot hope to arrive at a diagnosis of the predicament of man so long as one’s image of man is that of a conditioned reflex-automaton produced by chance mutations; one cannot use a stethoscope on a slot machine.”

Monod would probably have read The Ghost in the Machine before the two men met, in September, 1969, and been aware that Koestler had grabbed onto biological straws to try and make his case, quoting two well-known evolution sceptics – Sir Alistair Hardy and WH Thorpe. By that time, Monod would have been well-along with, if not having completed, his own book which was published in French in 1970 and in English as Chance and Necessity in 1971. In it Monod covers some of the same ground as Koestler does in The Ghost in the Machine, without Koestler’s literary strength but mercifully less verbose, he delivered a devastating critique of animism, vitalism and Marxism as unscientific forms of thinking amongst intellectuals. In this context he criticises the metaphysicist Henri Bergson and the pantheist priest Teilhard de Chardin, both dead by then, but makes no mention of Koestler and his writings on the subject. Too polite perhaps. Here at the Stockholm conference Monod had his opportunity to make his point with Koestler in person.

Why did this exchange matter to me?

I had been brought up as a Christian. My sixth form biology teacher was a well-known naturalist, who answered nature questions from listeners on the BBC. He was also a person of faith as many naturalists were in the 1950s. Knowing few if any non-believers, I had accepted the view, common in this Cold War era, that godless people were bad. By the time of the Stockholm conference I was in my late 20s and had recently completed a PhD in biochemistry. I bought a copy of Ghost in the Machine, plus books by Hardy and Thorpe, desperately searching for a spiritual dimension to Darwinism, but despite meeting Monod on two other occasions, the last in 1970 when he urged me to read his book, I did not read Chance and Necessity until 2012.

The reason I think is clear: I knew what it would say. Chance and Necessity was the pioneer book in a genre that would be followed later by Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene (1976) and Daniel Dennett’s Darwin’s Dangerous Idea (1995), books that after giving convincing evidence of the validity of modern Darwinian theory leave no room for any spiritual dimension. But they lay out the truth about how life came to be and has evolved on this planet. As Dennett’s book suggests, these books are dangerous reading, but they do tell scientific truth.

In hindsight my refusal to read these books for so many years was neither honest nor true to my scientific training. Jesus said: “The truth shall make you free.” But I had not sought truth wherever it might lead, but rather had avoided the further truth that might be in those books in exchange for comfort. I am not alone in this and the reasons are understandable. It may seem reasonable at first for the individual to choose not to know all the facts, but when many even in the intellectual community of the early 21st century seem unwilling to live in full reality and where opinions too often trump scientific truth, we could be building troubles for future generations to deal with. In America where I now live, scientific education is hampered by the powerful Creationist lobby, and denial of climate change prevents effective government action.

Jacques Monod was perhaps the first notable scientist to put in a detailed biological context the fully materialist nature of life. At the same time he was deeply concerned about man’s humanity and about issues of morality and justice. I got the impression of a decent man of great principle, lacking any cynicism, and who had time for me the inquiring young man. Koestler on the other hand, concerned, as he wrote, that science was eroding moral and spiritual values, was deeply cynical and notorious for his womanising and alcoholism, which created scandals that undercut his expressed global concerns. And yet, I, the young Christian, chose to read his book and not Monod’s.

Jacques Monod concludes his book with these words: “Where then shall we find the source of truth and the moral inspiration for a really scientific socialist humanism, if not in the sources of science itself, in the ethic upon which knowledge is founded, and which by free choice makes knowledge the supreme value – the measure and warrant for all other values? An ethic which bases moral responsibility upon the very freedom of that axiomatic choice…[man] could at last live authentically, protected by institutions which, seeing in him the subject of the kingdom and at the same time its creator, could be designed to serve him in his unique and precious essence.”

In their books that straddled the conversation in Stockholm, both men wrestled with the problem of the dark side of mankind. They understood this from first hand experience: both men came close to losing their lives fighting fascism in their youth. Koestler became obsessed with this split personality of mankind, what he called the Janus effect. Monod was not blind to the problems in this realm but believed that solutions lay in knowing more about ourselves, in deepening scientific understanding.

Not long after their meeting in Stockholm, both men were diagnosed with cancer. Koestler eventually committed suicide along with his younger, healthier wife, raising postmortem criticism that he allowed or even perhaps encouraged her to join him. Then some women reported that Koestler had forced himself upon them during seductions. His will decreed that most of his estate, about £1 million, should go to promote research into the paranormal through the founding of a Chair in Parapsychology at a university in Britain. Oxford, Cambridge and London universities were all approached and all refused. Koestler was without doubt a great writer who wrestled with some of the major issues that humanity has yet to resolve. We owe him much. Nevertheless, in his perhaps less gifted way, Monod’s rigid honesty, courage and decency pointed a better, though not at all easy, way forward. I am grateful that I am now discovering that way.

Bryan Hamlin forsook science for some decades to pursue faith-based conflict resolution work. Now in his retirement he is re-finding himself and his passion for science.