The seed sown at the moment our eyes met has grown rather, leading me to argue that the hedgehog is the most important creature on the planet – that between their muddy little paws is held the key to the salvation of humanity.

The argument is actually quite straightforward. At that moment I realised that there is no other wild animal with which it is possible to get this sort of connection. Pets have had the wildness banished through breeding. Throwing bread at ducks or putting out nuts for tits hardly gets you close. I have studied smaller mammals but, to be honest, once you have met one Bank Vole, you have really met them all. And as for larger animals, well, there is no getting close to them; they are either too fleet or too dangerous, or both.

The hedgehog is the perfect “Goldilocks animal”: just right. Not too big, not too small; and with a reaction, when frightened or cornered, not to run or attack, but to stay still. This is helped even more by their clear fondness for the suburban garden, meaning that our chances of seeing one are far greater than all other mammals.

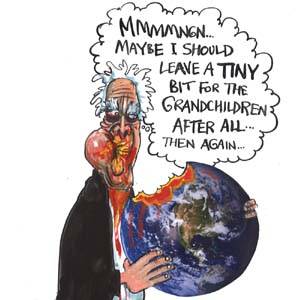

And why should this matter? Because we are continually being encouraged to fall in love with nature. The message from the conservation and wildlife charities is just that, because they recognise what was neatly summarised by Stephen Jay Gould, “We will not fight to save what we do not love.” And the biggest problem about “nature” is that it is just such so enormous. We need a “gatekeeper species”, something to lead us into a more profound relationship with the natural world.

But these organisations have made a big mistake. They are of the belief that only the charismatic mega-fauna – the whales, pandas, tigers and elephants – will tip us over into love. What came to me, lying on that lane, looking at Nigel, was that this is a bit like assuming gazing at the pictures of celebrities in Heat or Hello magazine will result in true love. I am as likely to get nose-to-nose with Angelina Jolie as I am with a humpback whale. We end up falling in love with the boy or girl next door, and that is where the hedgehog wins; it is the animal equivalent of the boy or girl next door. It is the animal we really have a chance of getting nose-to-nose with, of looking into the eyes and seeing the glimpse of something truly wild.

Strangely, you might think, there have been people taking issue with this quite reasonable assertion. And that was the motivation behind my second book – The Beauty in the Beast – in which 15 people around the country made it their duty to try and seduce me away from the hedgehog because they believed that their own animal was at least as remarkable as mine.

I enjoyed the simplicity of my challenge – to open myself up to the persuasive powers of people and wildlife. But then came a surprising complication. I was contacted by the organisers of ExtInked – a madcap project from Manchester art and design collective, the Ultimate Holding Company. They were collecting information about 100 species on the UK’s Biodiversity Action Plan to add to the illustrations being drawn. The hedgehog has, unfortunately, earned its place on this list – we now have a conservative estimate of a 25 per cent decline in the last ten years alone.

So where was the complication? ExtInked stood out from the norm thanks to the tattoo parlour being set up on a small stage for the opening few days of the show, at which 100 volunteers would be permanently inked with the pictures from the exhibition. They would each become an ambassador for their particular animal, plant or fungus. I decided that it would be a good way to mark the end of my month-long mid-life crisis – by getting my first and last tattoo of a hedgehog, of course.

Most of my friends seemed to think that my quest in The Beauty in the Beast was simply an excuse to find another animal for a tattoo – their addictive nature being legendary. I resisted, for quite some time. But eventually the sense of their argument ground me down and I decided that, if I was going to be serious about identifying a particularly special species, then how better to indicate the fact that it was a real choice than to commit to getting it added to my flesh as my second, and most definitely last, tattoo?

The first task was to choose which animals to meet. The publishers frowned at my original list of over 30 so I had to whittle it down to 15, losing moles, seals, even the boring piddock (that is its name, not a description). One day I hope I will get to meet them.What swiftly became apparent was that this process was going to be as much about the people as it was about the animals. There is a wonderful eccentricity that comes with the gentle obsession of British folk.

Take my otter woman for example. She is the poet Miriam Darlington and has just written a magnificent book called Otter Country. She took me down to the River Dart near her home in Totnes and, after some scrabbling, along to a cave that went deep under the bank. She had already pointed out that we would not see otters – since they are nocturnal and shy. But she had a mission. She wanted to find me some otter poo.

This did not bother me unduly. I long ago recognised and accepted that as a mammal scientist I was going to spend a lot of time among people obsessed with faeces; it is often hard to find the actual animal and you can learn a lot from their leavings. But the otter has the additional quality of leaving, apparently, the most fragrant of faeces, and it was this that motivated my poet-guide. Unfortunately our quest was unsatisfied and I emerged from the cave filthy, but without a sample.

A couple of weeks after my otter trip, I received a small parcel through the post. Inside was a little box with a picture of an otter on the front, and the injunction: “smell me”. Hidden deep in the cotton wool was a small plastic bag. I knew I had to – so I opened it and took a deep sniff.

My advice for anyone sent a dried sample of faeces through the post is: do not do this. It will have dried into a powder. After I had finished sneezing otter poo out of my nose, I decided to take a more delicate inhalation and, yes, Miriam was right. It is extraordinary. Earl Grey tea, hay meadows, jasmine with a hint of fish.

My bat woman, the energetic ecologist Huma Pearce, was determined to win. She tried to seduce me with a night out eavesdropping on flitting bats through her fancy electronic listening device, but what nearly won me over was actually meeting a brown long-eared bat. If you get the chance to meet one, you will see why. They have freckles!

I was also nearly won over by the badger. This was in part due to the wonderfully energetic guide, Gareth Morgan, and in part because it would have allowed me to say, had the badger ended up tattooed on my right leg, that I was the only man alive with an asymmetric intraguild predatory relationship between his legs. But in the end I decided I could not quite justify a tattoo on the basis of a single joke. Even if it was a joke that carried with it an important ecological concept explaining the complexity of the relationship between these badgers and hedgehogs.

Gareth took me to the badgers he had been watching for 30 years. As we talked, the badgers came out to feast on the peanuts he had tossed around for them. What was so moving was how easily Gareth talked of love. Some of my experts were hesitant at using the “L” word. But not Gareth. “I love them like I love my wife,” he said. “I am not saying ‘more’, because that would be dreadful.”

He explained the impact that “his” badgers had on some of the visitors. Healing the lame, calming the distressed and teaching a deep wisdom to those who were willing to invest a little time. I began to wonder where I had heard such claims before!

he power of this love we can share with wildlife is enormous and could easily be mistaken for something magical or religious. But I believe it is innate. So what to call it? There is too much riding on the one word already.

For help I turned to my friend Roman Krznaric’s book The Wonderbox. He describes how the Ancient Greeks identified six different varieties of love: eros (erotic love), philia (the love of friends), ludus (playful love), pragma (pragmatic love), philauteo (self-love) and agape (universal love). And makes the very good point that it is absurd we have a monoculture of just the one word.

Still, though, that does not answer my question as to how to define this relationship. Until, that is, I remember the work of EO Wilson, Harvard professor, ant specialist and great thinker. He popularised the term biophilia – he argues we have an innate need for contact with nature and that when we are away from nature we suffer. Perhaps that is something we should all embrace?

In the end, my quest had to have a winner and it was, rather surprisingly, the common toad. My toad man, Gordon Maclellan, runs “Creeping Toad” – an environmental education business. He has a brilliant capacity to attract and hold an audience – being tall, hairy and covered in tattoos. School groups cannot get enough of his eccentric storytelling, deep wisdom and connection to the earth.

He does all the things that good toad fans do – including helping them to cross the road when they are making their determined path towards ancestral ponds in the frenzy of the breeding season. But he also has a different toad motivating him, because Gordon is a Shaman and at the heart of his Shamanic world he has a large toad. Access to this world comes through dance. And after many fruitless (but wine-filled) nights during which I failed to understand what he was talking about, Gordon invited me to join him on a Shamanic dancing retreat up in the High Peaks of Derbyshire.

Until recently I would have refused point-blank. I don’t dance. Or rather I didn’t until the month of my mid-life crisis, as that included my first and last dance class, which, like the tattoo, proved rather addictive. The dancing I do is an ecstatic form called 5 Rhythms. And while there are many I sweat with who see this as a spiritual practice, I recognise the wonderful rush of endorphins in a safe space and have a great time.

The big difference between that and my weekend with Gordon was rather mundane. I had not realised we would be dancing outside. And it was cold; very cold. The grass had frozen into individual needles and the small stream was thickening towards ice. I had not brought enough clothes. My main conclusion was that it is particularly difficult to dance into a transcendent state while wearing tweed, as I had to resort to wearing everything I had.

But this failure to reach my inner toad did not distract me from the main thrust of this story. And that was to look out for the love and wonder that animals can generate for people. Certainly the toad managed it for Gordon.

And then, a few months later, came my turn. While I was camping in the New Forest and eating a bleary breakfast, one of the kids in our group came and sat with us, wearing his dad’s big boots. After a few minutes he jumped up, looking panicky. Something was crawling up his leg. I looked, and found a toad creeping up his calf. A very lucky toad, for his father’s feet would have made for a much more uncomfortable start to the day.

As I rescued the amphibian I got a chance to look at it closely. Really, I recommend you do this. They have golden, jewel-like eyes, and an attitude of quiet confidence, quite unlike the rather hysterical nature of their cousins the frogs. So many people got a good close look at this animal and so many people talked of how special the experience felt. It made me realise that there is an awful lot in common between the hedgehog and the toad. They both have a calm attitude. They will let you get close because they are well defended. And they both excite children.

So it was with a great deal of calm that I sat down in front of the tattoo artist and had the toad join the hedgehog on my leg. Both are perfect gatekeepers. In fact so many of the animals I met have the capacity to lure people into seeing the world in sharper focus.

Despite my special pleading for the hedgehog, I did sort of know this already. Getting up close and personal with many wild animals will teach you this. But the exercise of getting others to provide evidence for the qualities of their chosen species made me realise how many wonderful ways there are to get hooked. So whether it is badger or vole, toad or robin, bat or dragonfly – see if you can find something that will act as your gatekeeper species.

Gatekeeper species are important. It is pretty much impossible to fall in love with something as nebulous as “nature” – we need a way in or a mediator. And that is what these creatures have the potential to offer, if you are willing to take the risk of falling in love. Don’t get distracted by the A-listers – the charismatic mega-fauna. Remember, celebrities are distant and unobtainable. Fall for the girl or boy, or hedgehog, next door. It could be the start of a beautiful relationship.

Hugh Warwick’s book The Beauty in the Beast (Simon & Schuster) is published as a paperback in April. Visit his website at www.urchin.info