You know what you want to do? You want to go out and get thoroughly smashed. Zonked. That’ll get your mind off your worries. It’s the only way.”

I tried to look enthusiastic. Dave was only trying to help, doing his best to console me after the news had come through that another of my old friends had died.

What I couldn’t tell him was that I’d already tried his patent remedy. And it had failed. I’d sat at home immediately after hearing the bad news and conscientiously drunk my way through a good half bottle of Bells. But although I’d walked into the hat-stand as I made my way to bed and nearly swallowed a flossing stick, my gloom-laden thoughts about my old mate’s demise had obstinately refused to dissipate. Why him? Why now?

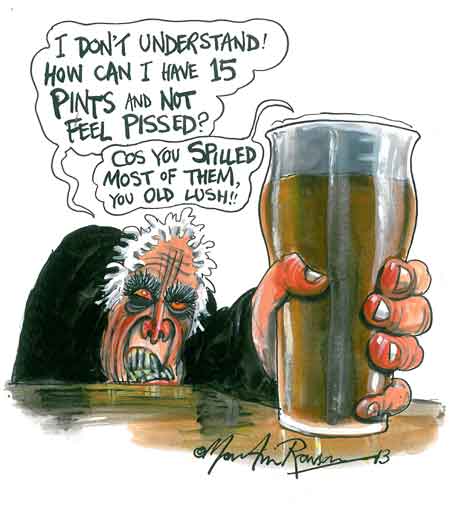

I wouldn’t have worried half so much about alcohol losing its transformational power if this had been the first occasion. But being unable to get thoroughly drunk, properly ratted, really out of it, now seems to have become a new fact of my elderly life much like my current inability to put on a pair of socks without slipping off the edge of the bed.

In the days leading up to Christmas this year, for example, I’d gone out on the town with a couple of good old boys from my Liverpool past. They wanted one of our old-time nights together. One of those great nights in which we simply got out of our heads and then waited for Fate to take its course. You never knew what might happen on such a night. You might make new friends, discover a great jazz club, get invited to a fabulous party, propose marriage to a cocktail waitress. It was all in the lap of the gods.

By ten o’clock that night it was obvious that my two mates were indeed body and soul drunk in a good old-fashioned way: they recounted time-honoured stories about girls they should have married, repeated jokes they’d told earlier in the evening, made eyes at every woman in focal range, seriously over-tipped the bar staff, picked their favourite Liverpool side of all time, and started to make plans for a trip to Las Vegas.

But although I could no longer make my way down the passage to the Gents without bouncing between the walls like a pinball, my head seemed to be in exactly the same place that it had occupied when I’d lifted my first pint of bitter a whole three hours before. While my legs shouted “arse-holed”, my mind quietly told me that I was as sober as I’ve ever been and that my so-called friends were making a pathetic show of themselves. What were they doing now? Singing “You’ll Never Walk Alone”? Really? At their age? Didn’t they know better?

When we staggered out into the night, there was no Fate waiting to take me on an adventure. London Town didn’t pick me up and carry me off to unexpected pleasures as it had done so often in the past. It stayed still and stared glumly back at me. There was nothing else to do. While my mates allowed Fate to direct their clumsy steps towards Soho, I spotted a taxi, made my pathetic excuse – “bit of an early start tomorrow” – and went home. When they turned to wave me goodbye I could almost see the phrase “wet blanket” etched on their slack lips.

My tame psychotherapist was no help. When I rang and told her about my drink problem she said it was probably down to boredom. My mind had had enough of me. It refused to get drunk in the good old-fashioned way because it knew the cortical consequences too well. It simply couldn’t stand any more of the maudlin sentimentality that I liked to pass off as wisdom and insight when I was more than two sheets to the wind. It simply couldn’t bear another outing of the chat-up lines I favoured when I was trollied, ripped and feck-arsed. It simply couldn’t bear to hear me telling some impressionable researcher or needy postgraduate that I felt that I enjoyed “a strange affinity” with them and wouldn’t they therefore like another drink and while we were at it how were they fixed for getting home.

“Just think,” she persisted, “your poor mind’s been listening to that crap for the best part of three decades. No wonder it’s decided that atrophy would be a better option.”

There is, I suppose, some slight consolation to be found in the fact that I can now drink very heavily and remain mentally alert, quick-witted, rational. Last night, for example, after a few pints and a couple of Jack Daniels in The George, I meandered home and after some fumbling finally got the front door to unlock. My partner was waiting in the hall. She gave me one of her best despairing looks. “Pissed again,” she said slowly. “Don’t worry, darling,” I said, allowing my still alert brain to handle the situation. “So am I.”