[This article is a response to Anglican in Angola by Rev. Joanna Jepson]

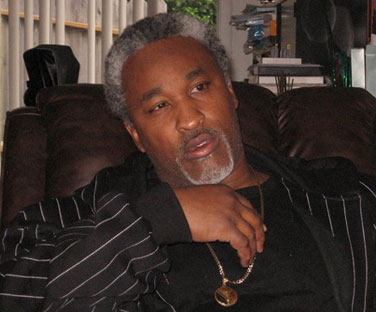

My friend Jerry Elster has a story of self-renewal in prison. As a young black man in Los Angeles Jerry tried to put himself through college by dealing drugs on the street: he was ambitious and careful. But one day a rival gang member challenged him on his turf. By the code of gang life he had a stark choice: kill the man or, if he let him go, expect his own gang members to kill him; if he fled, they would take it out on his family. He killed.

“At first, inside, when I learned how the American system stacked everything against us urban African Americans,” Jerry writes, “I got real angry. I did most of my first five years in solitary: ‘the hole". But I came to find out that my violence was hindering my progress, more than helping. I had to seek alternatives to violence. I had a spiritual awakening. I had to change my mindset.” As a result of this awakening and years of hard work, including getting two associate degrees and immersion in a restorative justice program, Jerry now says “I was free before they let me out.”

Today, three years since he was released after twenty-six years inside, Jerry works full time for prison reform, is completing his college degree and in his spare time works, along with his wife Miki, for restorative justice. He was one of my teachers when I trained to be a facilitator in the restorative justice program he had become expert in at San Quentin prison, the Victim Offender Education Group (VOEG). For a year now I have facilitated a weekly group there, mainly for lifers.

Jerry’s story is in some respects very similar to those Joanna Jepson tells in her piece about her time visiting Angola prison in Louisiana. Jepson tells of prisoners who have experienced “moral rehabilitation” through their involvement with the Bible College program of Warden Burl Cain. It was indeed a Christian commitment that first enabled Jerry to resist the codes of gang life in prison. He had been raised Christian, Christianity was the language his mind and spirit spoke in solitary: “So I humbled myself,” he writes, “I reached inwardly for strength and spiritual guidance. It brought me back to my Christian beliefs.”

Some humanists may be troubled by the fact that Jepson’s stories, like Jerry’s, show how important a religious or spiritual commitment can be to break the bonds of violence, enable prisoners to accept responsibility for harms they have caused and find a way to move on. But not me. As an ex-Christian agnostic, I don’t care whether Jesus saved Jerry or he saved himself with Biblical teachings, I am just happy it happened: the alternative would have been continued violence as a leading Crip in prison, and the bitterness that poisons the self. I am grateful there are as many varieties of experiential renewal as there are cultures, and I think it would be very arrogant and self-defeating of the non-religious to deny prisoners any avenue that might help them achieve this.

But what I do think matters is that whatever path to renewal a prisoner takes, it is holistic and fully aware of the context in which that person became a prisoner. The questions we should be asking of any prison programme are, therefore, not is it spiritual, but is it only concerned with individual accountability or that of society at large? Does it disavow violence as a whole or just individual crimes? Is it sincere about denouncing all violence, all injustice? Does it think it is the only way to redemption?

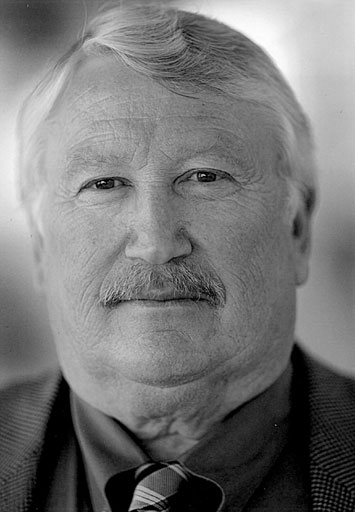

It is in relation to questions like that that I find Rev. Jepson’s wide-eyed praise for the Angola program troubling. I am astonished that she nowhere mentions that the American criminal justice and prison system is deeply racist, the more so since she is writing about a prison located on a former slave plantation in Louisiana. And can a Warden overseeing the largest prison in America – who she describes as “a straight-talking Southern-drawling boy in the body of a gentle, ambling grandfather” – really be quite the gentle soul she portrays? And is the religion Warden Cain espouses really as open-minded as she is? Jepson is Episcopal, that most tolerant of Christian faiths, and quotes Richard Rohr, a social-justice-loving mystic Franciscan whose work I admire, but the Angola Bible seminary is Southern Baptist, full of born-again evangelicals who would likely think Rohr, for one, is bound for hell, if not Jepson herself.

Jepson’s kindly Warden Cain was profiled by the US magazine Mother Jones in 2011.The article’s title – “God’s Own Warden” – and its tagline convey the gist: “If you ever find yourself inside Louisiana's Angola prison, Burl Cain will make sure you find Jesus—or regret ever crossing his path.” The author, veteran award-winning investigative journalist James Ridgeway, gives Cain his due as a man who in the words of a prison chaplain “cares about the downtrodden and disadvantaged in a way that's sadly missing in prisons across the US.” But Ridgeway also reports that “former prisoner, John Thompson—who spent 14 years on death row at Angola before being exonerated by previously concealed evidence—told me that Cain runs Angola ‘with a Bible in one hand and a sword in the other’. And when the chips are down, Thompson said, ‘he drops the Bible.’”

Some examples: During an attempted prison break in 1999, a group of five inmates took two guards hostage and killed one of them. What happened next was revealed at their trial, as Ridgeway reports: “Prisoners told of being beaten with fists, batons, bats, sticks, and metal rods… Several inmates said they were thrown naked and without bedding into freezing solitary-confinement cells, denied medical care, and threatened with death if they refused to sign statements that had been prepared for them. The events prompted an FBI investigation, and the state of Louisiana eventually agreed to settle with 13 inmates who filed civil rights lawsuits. But there was no admission of guilt, and no reprimand for Warden Cain.”

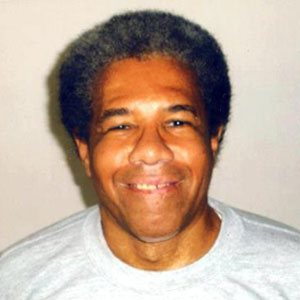

Two men have now been in solitary for over 40 years, most of that time at Angola. Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace founded the Angola chapter of the Black Panther party in 1971. At that time, if you were African American and wanted to organise against racism, segregation, brutal prison labor practices and systemic rape and sexual slavery in prisons, the Panthers would help you. Unfortunately once you identified as a Panther it also became easy for the authorities to denigrate (brief pause to contemplate the etymology of that word) and even frame you. That is what apparently happened to Woodfox and Wallace when a prison guard was killed at Angola.

Warden Cain made it perfectly clear in a 2008 deposition that he kept them in solitary all those decades for political reasons. He said Woodfox “wants to demonstrate. He wants to organise. He wants to be defiant...He is still trying to practice Black Pantherism, and I still would not want him walking around my prison because he would organise the young new inmates. I would have me all kind of problems, more than I could stand, and I would have the blacks chasing after them.”

So Woodfox, now 66, has spent more than half his life in a prison cell just three paces wide by four paces long. He spends 23 hours a day in his cell, and is allowed out only to walk along the cell corridor, shower, or exercise alone. He is deprived of access to work, rehabilitative programs, and group activity. As a consequence of these conditions, his physical and mental health has deteriorated. Amnesty International, who are campaigning for his release, say “his case paints a disturbing picture of justice in Louisiana”.

Yet, according to his own testimony in a recent documentary, Woodfox is sustained and protected by his faith. “If a cause is just noble enough, you can carry the weight of the world on your shoulders. And I thought that my cause, then and now, was noble. So therefore, they could never break me. They might bend me a little bit, they might cause me a lot of pain. They might even take my life. But they will never be able to break me.” Too bad then for Woodfox that his faith in justice and the truth is the wrong kind of faith, and he therefore does not qualify for the kind of redemptive programme Warden Cain offers to inmates prepared to accept the supremacy of the Bible.

But in my view Woodfox’s faith is no less valid than the conversion of Cain’s new Pastors, and as Jerry’s story shows the two – Christian redemption and a commitment to racial justice – can be combined. By their testimony it is the US prison system that urgently needs a spiritual renewal and redemption of its own.

Here’s why: In 1972 fewer than 350,000 people were being held in U.S. prisons and jails, and, according to lawyer Michelle Alexander in The New Jim Crow, a definitive analysis of the racial injustice of the US prison system, some optimists were even predicting that the prison system would fade away altogether. Today the US prison population is over 2 million. African Americans make up around 13 per cent of the total US population, but account for 40 per cent of the incarcerated.

Alexander compares the U.S. with Europe in the same period: “Between 1960 and 1990… official crime rates in Finland, Germany, and the United States were close to identical. Yet the US incarceration rate quadrupled, the Finnish rate fell by 60 per cent and the German rate was stable in that period.”

Why did this happen? It’s tempting to blame rising crime, but in fact crime in the US has not risen by anything like this over the same period, and in many places it’s seen a steep decline. What about drugs? Does the excessive use of illegal drugs by America’s black population account for this discrepancy? It does not. According to Alexander, “Studies show that people of all colors use and sell illegal drugs at remarkably similar rates.” It’s not drugs per se, but the War on Drugs, launched by Ronald Reagan in 1972, which appears to be behind this incarceration epidemic, a war on drugs that has been both unbelievably ineffective in curbing drug use in America, and has amounted to a virtual war on black communities. Just one example of the way the system was stacked against the black poor: penalties for crack, mostly used by blacks at that time, were set at 100 times the severity of those for powder cocaine, used mostly by whites.

For Alexander this amounts to a conscious attempt to crush the political threat represented by the Civil Rights movement and the Black Panthers: “a racialised social control that functions in a manner strikingly similar to Jim Crow.” Some might be tempted to dismiss all this as leftist propaganda; yet Alexander provides reams of compelling evidence. I urge you to look at it yourself, and while you’re at it listen to this stunning 1981 interview recently unearthed by The Nation. Here former Republican strategist Lee Atwater explains the “southern strategy”, that brought Nixon, Reagan and two Bushes to power, which comprised winning the white vote through barely veiled appeals to racism.

I am a white immigrant to America of left-liberal opinions who has lived here for over thirty years and yet I had no idea of the reality and extent of legalized torture in US prisons. My eyes were opened by a documentary produced, perhaps surprisingly, by National Geographic magazine. The movie takes us inside maximum-security prisons to reveal the mind-destroying reality of the solitary confinement that tens of thousands of Americans are subjected to every day. There were only a handful of people at the viewing I attended with Jerry and Miki Elster in Oakland. Very few white Americans want to know about these things.

I also had no idea that slavery had never been fully abolished in America. The 13th Amendment of 1864 reads in part (my italics): “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States...” At Angola the prisoners, three quarters of them black, working the land by hand, are paid between 2 and 20 cents an hour. As broadcast journalist Amy Goodman says of Angola: “It still exists as a forced-labor camp, with prisoners toiling in fields of cotton and sugar cane, watched over by shotgun-wielding guards on horseback.”

With so few Americans aware of this it’s hardly surprising that Joanna Jepson remains in the dark. None of this means that the many prisoners who have been reached by Cain’s Bible seminary, or the dying inmates who were comforted by those he spiritually redeemed, are not far better off than they would have been. There are many paths to salvation.

Yet there are specific reasons why we should be cautious about over-celebrating Warden Cain’s achievements, and questions we must continue to ask: Will Cain continue to deny prisoners the right to other avenues of self-renewal? Why does his prison perpetuate the violence, torture and forced labour which seems to run contrary to his avowed Christian principles?

But deeper than that we have to recognise that if we want violent offenders, and especially African Americans, to acknowledge the wrongs they have done, renounce violence and rejoin society, that society, too, has to find a way to change its behaviour, acknowledge its role in creating and sustaining a culture of violence and injustice, and a way to heal itself.