In many ways Singapore is a place like no other. A former British colony, the tiny island in South East Asia is one of the worlds leading financial centres. As a nation it is fantastically wealthy, clean and safe with a well travelled, well educated populace.

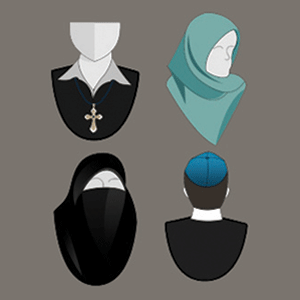

The population is racially and religiously diverse, with about 74 per cent identified as Chinese, 14 per cent Malay, and nine per cent Indian, with so-called “Eurasians and others” making up the remaining three per cent. This sundry mixture of peoples is divided into the following religious affiliations: 33 per cent Buddhist, 18 per cent Christian, 18 per cent no religion, 15 per cent Muslim, 5 per cent Hindu, andf 9 per cent others

It is striking that 18 per cent report that they have no religion or do not belong to a faith group. This means that the group identified as “secular” or “unaffiliated” is just as significant, if not more, than the population of many major religious groups.

Yet this group has less protection under Singapore law compared to their religiously-inclined neighbours. The faithful in Singapore enjoy legal protection of their beliefs and feelings, and almost-complete freedom of expression of their beliefs. Those not of faith are not similarly protected.

The government of the independent Republic of Singapore retained many features of its predecessor, the British Crown Colony. The legal system is based on English common law. There is a democratically-elected Parliament, together with the executive arm of government and a prominent judiciary.

Since obtaining self-governance in 1959 and then independence in 1965, the country has been ruled by the People’s Action Party or PAP. The PAP prides itself on being non-sectarian. It exercises the party whip to ensure parliamentarians vote in accordance with the party line, not personal faith or affiliation. The whip has only been lifted a handful of times to accommodate MPs’ religious sentiments – one of which was the vote on the passing of the Termination of Pregnancy Act to legalise abortion.

Given the nation's diversity of race and religion, the government is careful to be seen as even-handed in its dealings with major religious groups. The larger religious communities each have an umbrella organisation, through which their appointed leaders are regularly consulted on government policies.

The Singapore government’s primary concern is to avoid religiously fuelled dissension or conflict. To this end, it wields an arsenal of different laws against individuals who are deemed to cause discord between religious groups, whether by word or deed.

This means, for example, that it is a criminal offence under the Penal Code to wound someone’s “religious feelings”. It is worth noting that the Penal Code was written by a Scotsman for use in 18th-century India, subsequently transplanted to colonial Singapore, and very little has changed since. The Internal Security Act is a heavy-handed law which provides for detention at the government’s pleasure without trial, It has been used both against alleged terrorists (after the 11 September attacks in the US) and persons deemed to be agitating inter-religion unrest. In at least one case, criminal sanctions were imposed on members of one religious group of Christians who attempted to proselytise to Muslims.

Fair enough: people who seek to incite discord between various faith groups ought to be restrained. But the views and beliefs of persons who are not religious are not recognised or protected in this way.

Neither is there any legal bar against offending those who are not religious or are sceptical of religious claims, or indeed against proselytising or imposing one’s religious views on the non-religious. Non-believers seem to be fair game for religious proselytisation, as well as ridicule and abuse.

This makes for a delicate situation for anyone who would like to express their scepticism of religion or religious claims as part of public intellectual debate. A curious asymmetrical situation indeed.

By way of example, one of us (van Wyhe) experienced first-hand something of this asymmetry. He noticed that tables showing the percentage of various countries’ population that accept evolution did not include Singapore. Surely it would be interesting to see how Singapore compares to other countries? However, he was told that this was not feasible because the matter was politically sensitive. This is surely overly cautious – if a Muslim-majority country such as Turkey can be polled, why not Singapore, with her diversity of views? How can it offend anyone to enquire about the public understanding of science? Evolution has not been scientifically contentious since the 1870s. It is taught in Singapore’s schools and universities, and government funding supports cutting-edge research in the biological sciences. How can it be a taboo topic for public discussion?

Conversely, some churches in Singapore display signs openly mocking evolution. One church displays a sign showing a man progressively becoming a chimpanzee declaring: “Are they making a monkey out of you?” and another asserts: “The theory of evolution is false!”. Religious groups can, and do, make bold assertions because they fear no backlash or repercussion from challenging the scientific or non-believing community.

For many years there was no official representation of non-believers, no organisation that professed to speak on their behalf. Such absence of representation may have contributed to the marginalisation of the secular community in Singapore.

This changed when, in January 2010, a small group of activists sought to register the Humanist Society (Singapore) as the country's first official humanist society. The HSS was formed to be the umbrella organisation for humanists, non-believers and atheists, and to promote scientific and rational thinking in the country.

As of March 2013, the group has about 200 members. It organises a few events each year such as Darwin Day and discussions on humanism, science and philosophy. The group also responds to current affairs issues by writing to newspapers and has recently been invited to comment on ethical, legal and social issues in Neuroscience Research by the Singapore Bioethics Advisory Committee.

Given the legal restraints described above, the young group and its members have taken care to stay well within proscribed boundaries. Members have been frustrated when they are unable to provide a strong response to religiously-motivated opinions, for fear of causing offence, even if unintentional. They are doubly disadvantaged by not having any protection from aggressive proselytisation. State censorship has led to a widespread culture of self-censorship: rigorous intellectual debate is stifled.

Yet with the prevalence of social media, ideas are quickly disseminated. Unless a person lives completely without access to the internet or the print media, they cannot avoid contact with ideas that are upsetting to their view of the world or offensive to their “religious feelings”.

Frank and open dialogue is a better way to manage the perceived sensitivities of different religious groups. The only way those with mutually contradictory views can co-exist in the current legal system is not to communicate. Surely it would be healthier if people were able to discuss their views without the threat of prosecution, free from the fashionable belief that there is a “right not to be offended”?

We believe that if Singapore aspires to be a leading developed nation, it must discard archaic laws which are no longer relevant to an educated, dynamic populace. If different and, let’s face it, mutually exclusive and contradictory religious groups can co-exist harmoniously in Singapore and even receive equal recognition and protection at law, it is only natural that those who profess no faith receive the same protection and recognition.

John van Wyhe is a Senior Lecturer in the Departments of Biological Sciences and History at the National University of Singapore, and Director of The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. Huifen Zheng is a corporate counsel, and sits on the executive committee of the Humanist Society (Singapore).