It was only after I’d spent the best part of ten minutes studying the menu in the newly opened Côte restaurant at the bottom of my street that I realised I was in quite the wrong place. Why on earth was I so earnestly trying to choose between Goat’s Cheese Terrine and Warm Roquefort Salad for my Starter Course and between Roast Sea Bass and Lamb Shank for my Main when only one brief hour before I’d consumed a perfectly good dinner of grilled steak and oven chips in my own home?

The answer was sad. Very sad. I realised that I’d wandered almost without thinking into my local Côte not because I was hungry but simply because the reception staff and the waiters had been so exceptionally nice to me on my last two visits. It wasn’t the food I wanted at all. It was the attention: the greetings and the smiles and the thanks.

Of course, I know only too well that staff in restaurant chains like Côte and Strada have to undergo an extensive training in customer service. They spend hours and hours being taught how to smile and how to show a personal interest in every diner. They are taught at length how to apologise for any faults in the service or the food. They’re told repeatedly how to say goodbye and come again and thanks so much for your custom and “good heavens, is it still raining?”

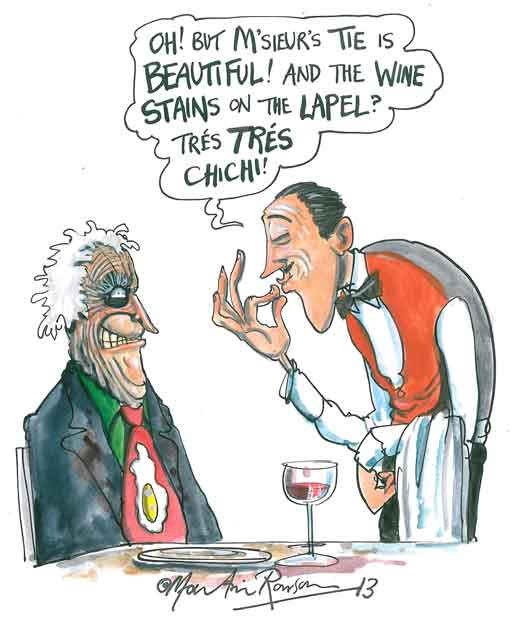

It’s called emotional labour: the ability to persuade mere customers that they are receiving the type of smiling attention that would normally be reserved for intimate friends and lovers. It’s a considerable skill. At my stage of life I find it something of a struggle on an average evening to work up more than two or three halfway decent smiles for my beloved partner. Imagine having to summon up enough bogus emotional resources to please the hundred or so customers who pass before you on an average night at Côte. That’s hard emotional labour.

But the knowledge that I’m only receiving trained smiles and trained pleasantries doesn’t worry me at Côte. They do it so well there that I simply can’t get rid of the idea that they are really pleased to see me, that the very first person they hoped would wander into their restaurant on a cold spring evening would be an elderly and slightly stooped academic with a very heavy damp greatcoat and long scarf and gloves which he couldn’t find although he certainly left the house with them and must have put them somewhere and a preference for sitting in one of the quieter areas and by the way do you have anywhere near the window?

I can appreciate that they’re taught to say “Hello” nicely, but who taught the charming and obviously intelligent young lady on reception to notice my new black and white shoes? Who taught her to say, “I do love your shoes” in a way that suggested she’d quite honestly in all her born life never seen shoes that were even half as interesting? Who gave her lessons in that? And when I explained, albeit at some length, that they were often called “co-respondent’s shoes” because back in the ’50s they were the type of flashy shoe worn by the professional men who helped their clients secure a divorce by pretending to commit adultery with a particular respondent, when I’d explained all that, and when I’d added in an extra bit about the photographers who had to hide in the wardrobe of the Brighton hotel where the adultery was to be simulated, who taught her to smile so broadly and say so very engagingly, “That’s a really funny story. Now, let me show you to your seat”? Who taught her that?

As I glanced again at the menu wondering whether despite the residual murmurings of the steak and chips I could possibly force down a very light starter, perhaps the Chicken Liver Parfait, topped off with Salmon Fishcakes from the Light Mains. But then if I had the fishcakes I wouldn’t have a chance to spend the best part of £35 on the grand cru St Emilion which had earned me such a broad approving smile from the waitress who’d served me two days before. “Good choice,” she’d said very quietly as though anxious not to let the other diners know about our incipient affair.

There was another receptionist on duty when I left the restaurant. She looked as pleasant as every other member of staff in the place and not only insisted on helping me on with my coat but waited very patiently while I repeatedly checked each of the pockets for a missing glove. “I’m always losing mine,” she said consolingly as she pulled the heavy damp greatcoat over my shoulder. And when the missing glove finally fell out of one of the coat sleeves she laughed delightedly. “There we are, sir.” There really was no doubt about the pleasure she took in my company. “We hope to see you again soon,” she said, reaching for the door handle. “And by the way, I do love your tie.”