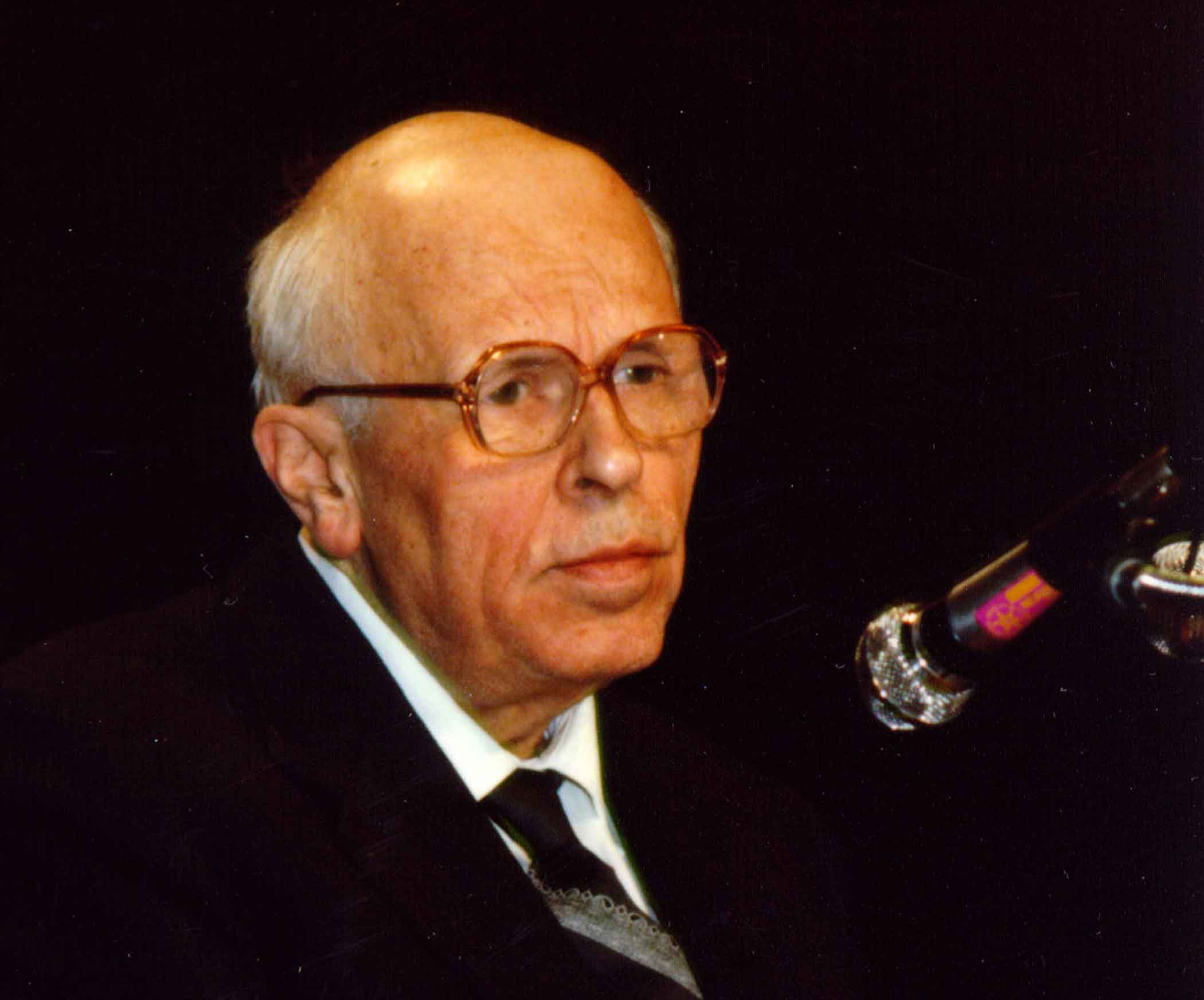

One of the better known dissidents who spoke out against the Soviet dictatorship in the '70s and ‘80s was nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov. After he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975 the pressure on Sakharov and his wife Elena Bonner increased. Threats were made against Bonner's family, especially her daughter Tatiana and her husband Efrem Yankelevich and their children. The family came to the sad conclusion that the Yankelevich family should emigrate and they arrived in the Boston area in late 1977. My wife and I soon became friends with them.

Then, when Sakharov spoke out against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979, he and Elena were arrested and deported to the closed city of Gorky. There Sakharov wrote his memoirs; more than once, in fact, as large amounts of the manuscript were repeatedly confiscated by the KGB, on one occasion as many as 900 pages. Not only did Sakharov eventually gain ground over the confiscations but piece by piece the manuscript was gotten to Boston where Efrem acted as literary agent, finding a publisher and arranging for translation into English. Memoirs by Andrei Sakharov was eventually published by Alfred Knopf of New York in 1990. A shorter follow-on book entitled Moscow and Beyond: 1986-1899 was published in 1991.

In the early months of 1989 there was a need to get a part of the memoirs back from the US to Moscow, where Sakharov was again living, for checking. On the first attempt the manuscript was confiscated. Hearing that I was making my first visit to Russia as part of a group, Efrem asked me to take the material in. How could I refuse? We decided that I would simply carry the manuscript in a briefcase.

All went well at Moscow airport and so on checking into my hotel I phoned Alexander, an aide to Sakharov. After I told him what hotel I was in he said for me to meet him in 45 minutes at the Octabryaskaya metro station. "How will I recognize you?" he said.

Thinking I knew the drill, I said: "I’ll be carrying a copy of Pravda."

After a pause Alexander replied "That’s not funny." In my ignorance I had chosen the Communist Party newspaper.

Nevertheless, I acquired a copy of the paper at the front desk and asked for directions to the metro station. That turned out to be a more serious mistake. Saying that I might get lost, the concierge summoned a young man in a grey suit who quickly materialised and, despite my several protestations, insisted on accompanying me along the road. It was clear to me that the young man worked for some branch of the Soviet security services. As we approached the station I hoped and assumed that Alexander would have the sense to keep his distance. The security man asked if I wanted to see Moscow’s excellent metro system. As he explained how the tokens were to be used in the turnstiles, I had an idea. "You go first," I said. He put his token in the machine and as the turnstile locked behind, I ran.

I made myself stay in the doorway for some time. Then with great trepidation I walked back to the metro station, a huge statue of Lenin looking down on me. Was the security man still going to be there? No sign of him. Then I became conscious of someone walking parallel to me but not close and then saying my name. I followed Alexander to a park bench, of course, where to my horror he very publicly inspected the contents of the briefcase. I was only too happy to leave it with him.

What would happen on my return to the hotel I wondered? Sure enough a woman who identified herself as with security said that I had been behaving "too independently" – I was supposed to be part of a group. I apologised and made sure that I behaved myself for the rest of the week. On leaving Moscow I went through all the usual checks and searches and to my relief reached the departure lounge to await the Pan Am flight to New York. Then a man – they were always in grey suits – came into the departure lounge and called out my name. I raised my hand. "Come with me, there’s an irregularity in your papers."

So this was how they did it. Get me away from my group, I miss my flight and would never be seen again! With heart pounding I said "No".

"What did you say?"

"I said no, because I’ve already cleared exit customs and security and everything else and my flight is about to be called."

This is when Sergei, as he had identified himself, made his mistake. He exploded with anger and shouted – I remember every word – "In the name of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union I order you to come with me!" Several of the men in my group heard this and gathered round asking me what was up. After I explained to them, one of the bigger men (I‘m not very tall) put his arm around my shoulder and said to Sergei, "Bryan’s going nowhere". There was a pause which felt like forever and then Sergei turned and stormed off. Moments later our Pan Am flight was announced for boarding and I was one of the first to hurry down the ramp to the plane. After we had taken off and the seat belt sign went off one of my companions came down the aisle, handed me a bottle of vodka and said, "Have a drink of this."

Andrei Sakharov died suddenly, while working at his desk, six months later in December 1989 before his memoir books were published. The following April I travelled to Moscow with Leif, a Norwegian friend who had campaigned for Sakharov to be awarded the Nobel Prize. I could not believe my eyes as we walked from the plane up the connector ramp to see none other than Sergei standing at the top. As I drew alongside him I said, "Sergei, da?" He nodded, "Da." It was quite clear that he remembered me. Leif and I moved on into the airport.

One of our visits was to Sakharov’s widow Elena Bonner. It is customary in Russia to take one’s shoes off when entering a home. Elena pointed to a well-worn pair of slippers and said, "Put those on, they belonged to Andrei Dmitrovich." What a privilege it was to have helped with his message in a small way, and to actually walk in this courageous man’s shoes for a short while.