She took a step. She actually took a step.”

“Not really. Not a proper step. She simply put one foot in front of the other.”

“Watch now. She’ll show you. Watch her now. Just watch.”

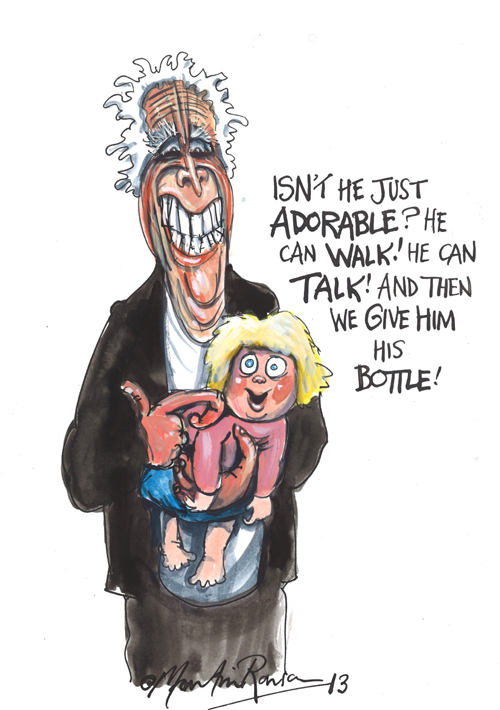

And with that I once again seized hold of my one-year-old grandchild, stood her up so that she could grasp the side of the chair with her pretty little fingers, and then crouched on the ground a few inches in front of her and cooingly enticed her to step towards me.

“Come on, Rose. Come on, Rose. There. That’s it.”

It was only as the little girl once more toppled to the floor with all the grace of a laundry bag that I turned round and realised my friends had quite deserted this demonstration of little Rose’s emergent abilities and gone to the other side of the room where they could discuss adult matters without being interrupted by my wheedling baby talk.

“Why on earth do you go on so much about her?” said Gerard when he’d finally dragged me away from the sofa where I was busy making sense of Rose’s gurgles. “I mean it’s not as if you’ve ever shown any interest at all in children. You’ve certainly never noticed my two. And I can’t remember you talking about your own boy with one tenth of the affection you display towards this baby. And don’t give me that old Freudian stuff about grandparents getting on so well with their grandchildren because they share a common enemy. That’s hardly explains your present descent into infantilism.”

“How d’you mean, ‘infantilism’?”

Hadn’t I noticed that, only this afternoon, while the rest of the room had been talking about how Ed Miliband had been forsaking even the most basic Labour ideals in order to bring himself into line with the findings from his focus groups, hadn’t I noticed that, while all this adult political analysis had been going on, I had been busy lying on the kitchen floor absurdly trying to teach a one-year-old child to play a toy xylophone.

“She can already play a few notes. She really can.”

“No, she can’t. You wrapped her podgy little fingers round the wooden stick and then forcibly moved her arm up and down. You were playing the xylophone. You. She wasn’t even looking at the bleeding xylophone while you were moving her arms. She is a baby and quite incapable of playing anything. She is not musically talented. She is not capable of speech. She can’t walk. She is a baby. Say it. Baby. Do you understand?”

Gerard did have a point. I have always ignored babies. Whenever I’ve been in Broadcasting House and spotted the arrival of a former employee clutching a bundle of swaddling clothes I’ve hastily repaired to the end of the office and busied myself with the shredding machine. And I’ve adopted much the same attitude towards photographs of the new- born which are frequently pushed in my direction.

When Gloria came in with photographs of her little one and everybody, simply everybody, started to say what a lovely smile she had, I casually announced that it wasn’t a real smile. What did I mean, chorused the baby lovers? Well, I explained, you’ve only decided that the baby’s expression is a smile because of the context. There are experiments in which mothers are separated from their babies by a soundproof one-way screen. The babies are then either tickled or jabbed with a needle. It turns out that mothers who can only see but not hear their baby routinely mistake its expression. They say that their little darling is smiling even though the experimenter is sticking a needle in its thigh. And another thing. You child didn’t say “mama” because it recognised you. It said “mama” rather than “waga” or “kaga” because you reinforced the first sound with a stroke or a smile and ignored the other noises. It’s what Skinner called operant conditioning.

When I saw Rose again this weekend I couldn’t get Gerard’s “infantilism” taunt and my own history of baby hating out of my head. There was no doubt about it. I had been acting in an absurdly sentimental manner. This little wriggling thing next to me on the sofa was an unformed human being and to give it credit for skills and emotions it couldn’t yet possess made me guilty of crass sentimentality. Before the year was out I’d be believing in Father Christmas and the Tooth Fairy.

But then, as Rose threatened to throw herself to the ground from the sofa, I found myself leaning over to restrain her. As I did so she clasped my hair with her little fingers and pulled very hard. When I looked into her face I could see that she was laughing. Not smiling. Really laughing. And gurgling. What was she saying? I leaned nearer.

“Sucker,” said Rose, with an almost frightening clarity. It’s something I’ve so far not chosen to mention to Gerard.