The superstar American comedian Louis CK’s polemic against smartphones, delivered in September on the Conan O’Brien show, was a clever piece of writing and acting, deftly weaving together a range of popular anxieties: about parenting, about social disconnectedness, about no longer being in touch with one’s true inner self. According to CK, the kids who are able to detonate their cruelty from a distance on social media, and the adults who can no longer be moved by a song in the car without frantically texting their friends, are equally affected, made lesser people, by the slabs of metal and plastic they carry in their pockets. The most existential part of the complaint was quoted for truth all over the internet: “You need to build an ability to just be yourself and not be doing something. That’s what the phones are taking away. The ability to just sit there. That’s being a person.”

The performance piece hit a nerve that has been exposed for some time. Jonathan Safran Foer had tickled it back in June, with a piece for the New York Times entitled “How Not to Be Alone”, in which he lamented how smartphones had robbed him – and, by extension, us all – of empathy. Earlier there had been a film by Henry Rubin, Disconnect, and a book by Sherry Turkle, Alone Together. All of them played with the same small set of hypotheses: that modern communications technologies make us more informed but less wise, more connected but less attuned to the needs of others and to our own true feelings.

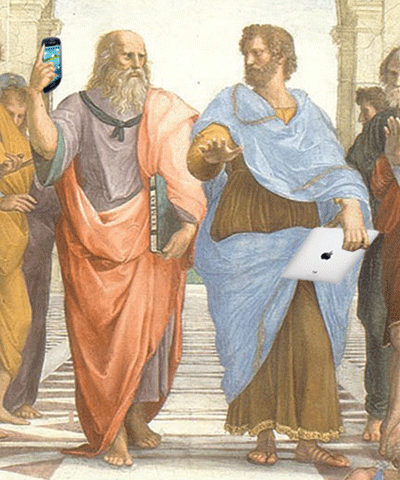

As it happens, these sorts of complaints may be as old as tool-making itself, seeing as the oldest to have reached us is also the earliest that could possibly have been recorded. It concerns the invention of writing, as denounced in Plato’s Phaedrus by means of a parable told by Socrates. In the parable, the inventor of writing – the Egyptian god Theuth – boasts to king Thamus that his innovation would make people wiser and improve their memories. The king sardonically replies that it would in fact make people merely acquire the appearance of wisdom, and that it would make them forgetful of how to remember.

With the benefit of 24 centuries of hindsight, this might strike us as a paradoxical complaint. Perhaps not entirely wrong – insofar as the art of memory as practised by the Greeks circa the time of Homer is largely lost to us – but rendered irrelevant by the enormous advantages that literate cultures enjoy in terms of their ability to produce and share knowledge. There is another paradox in the fact that Plato put the parable in the mouth of the last great Greek oral philosopher, whose ideas he had chosen to put down in writing. Finally, the paradox was one of Socrates’s own tools of the trade; a strategy he used to challenge the common beliefs of contemporary Athenians.

We could choose to interpret CK’s monologue along the same lines: as a paradox designed to illuminate our complex relationship with digital technologies, not quite to be taken to mean what it appears to be saying.

The problem with this hypothesis is the distinct lack of things being illuminated. For about a week after the Conan O’Brien show, every second person with access to social networks shared the clip, either approvingly or – less frequently – expressing an equally polarised disapproval. Louis CK is right. Louis CK is wrong. These viral reactions across the pathways of social media are so predictable that for a while I struggled to remember which came first: Louis CK’s speech or the “I forgot my phone” video, another indictment of how smartphones are eroding our social skills in the form of a two-minute YouTube clip that accrued millions of views within days of its release. (It was the video, by the way.) The two blended together in my memory because they generated the same rote responses, the feeling of déjà vu reaching all the way back to Socrates and Plato.

One problem with these critiques is that they seldom stand up to the most cursory scrutiny. CK’s nostalgia for the time people used to spend driving alone listening to the radio is the arbitrary longing for an older technology of distraction. But older technologies aren’t necessarily better. We’re just more used to having them around. There is also the matter of CK being an entertainer with his own television show, thus someone whose actual job is to distract people – a contradiction he doesn’t seem interested in pursuing.

Beyond the particular merit of each critique, however, are the grooves in which the responses fall, for and against, never crossing, always returning to the same common places, as if these observations about the social and psychological effects of new technologies had always been just made that morning, instead of being with us since the dawn of recorded time.

A way out of the impasse, then, is precisely to retrace those historical steps, document how the introduction of past technologies was greeted by their contemporaries, and reflect back on the present. There is a rich literature in this area, owing more to Frances Yates’s seminal study The Art of Memory than to the works of Marshall McLuhan, but these days I find myself turning more and more to the American media and social critic Neil Postman, a conservative polemicist, in many respects, who – were he still with us – might perhaps have railed against smartphones and the internet himself, as he did against television in Amusing Ourselves to Death. But also someone who understood that the challenge of engaging critically with our communication technologies is grounded in history.

Postman’s most important book, Technopoly, discusses the parable of Thamus and Theuth. It proposes that Plato’s entirely correct insight was that writing would profoundly transform what people meant by the word “memory”, even though they might – and in fact did – continue to use the same word rather than discarding it in favour of another. These semantic shifts are at the core of sociotechnical change today. Think again of what we have come to mean by “memory”, or “information”. Think of the word “social”.

In his new book The Writing on the Wall, Tom Standage has sketched a history of the first 2,000 years of social media – from the messaging network that kept intellectuals such as Cicero abreast of public affairs at the dawn of the Roman Empire to Twitter and Facebook – attempting to show how the study of what he calls “really old” media (based on the capillary distribution of information from person to person, as opposed to the mass model of newspapers and television) can assist in understanding not just digital media but the debates that surround them, for instance concerning their political impact. Such perspectives shift us away from the tyranny of the first-person observation, and towards understanding our communication technologies within their complex social, political and economic context.

Could it be that many of the anxieties that are associated with smartphones, including their compulsive and addictive qualities, are in fact a by-product of late capitalist societies in which economic precarity has become a cultural norm, as opposed to being inherent to the devices themselves? Might we be able to invent different uses for smartphones, or revolutionise their design, if we came up with alternative and less profit-driven models of production? Would it be possible for us to de-monetise the word “social” without resorting to the reactionary and frankly unthinkable outright rejection of modern communication technologies?

These are political questions, even utopian ones, but educators all over the world are faced with similar ones every day as their classrooms shift from print to digital resources. The industry has no shortage of salespeople who, like the god Theuth, are willing to swear that their technologies will make the children wiser and improve their memory. The answer is not to reject that claim out of hand but to examine it critically. It’s the unique teaching moment of our time.

Tom Standage’s The Writing on the Wall: Social Media – the First 2,000 Years is published by Bloomsbury