Saudi Arabia is hardly known for moderate policy making. Law in the theocratic kingdom requires that all citizens be Muslims (an overseas national seeking Saudi citizenship must convert), and religious police enforce modest dress and separation between genders. There is no legal protection for freedom of religion and conversion from Islam to another religion is punishable by death for men and life imprisonment for women.

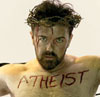

Against this backdrop, it should come as little surprise that atheism is frowned upon, to say the least. But now, a series of new laws on terrorism – in the form of royal decrees and an overarching piece of legislation – have included atheism in the definition. Article 1 of the new law on terrorism bans "calling for atheist thought in any form, or calling into question the fundamentals of the Islamic religion on which this country is based".

The decision to define atheism as terrorism has grabbed international headlines: the association jars, as in today’s climate, terrorism is more commonly associated with religion. It’s worth noting, though, that the wording of Article 1 is so broad that it covers not just atheist proselytising but any demands to reform laws based on religious principles.

And of course, the new legislation and guidelines go much further than that. The most striking thing, in fact, is quite how broad the new definitions of terrorism are. Saudi Arabia has followed Egypt’s lead in characterizing the Muslim Brotherhood, a pan-Arab social and political movement, as a terrorist organisation. In a bid to clamp down on the growing number of Saudis travelling to take part in the civil war in Syria, King Abdullah issued a royal decree criminalising “participating in hostilities outside the kingdom” with prison sentences of between three and 20 years. This reflects anxiety about these returnees, who are coming home with battlefield experience and ideas about challenging authority and overthrowing leaders. The crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood – long suppressed in the region, but emerging as an electoral force after the Arab Spring revolutions – demonstrates continued concern about contagion from the political unrest still wracking the Middle East.

Overall, the provisions for terrorism are so broad as to almost render the term meaningless. As Human Rights Watch puts it, the laws “create a legal framework that appears to criminalise virtually all dissident thought or expression as terrorism”. The organisation points out that the new legislation uses wording that prosecutors and judges are already using to convict peaceful dissidents and independent activists. Several prominent human rights activists are currently in jail in Saudi Arabia. Waleed Abu al-Khair and Mikhlif al-Shammari recently lost appeals and will begin sentences (respectively three months and five years) for criticizing the Saudi authorities. Late last year, a judge recommended that Raif Badawi, a blogger who had already been sentenced to seven years imprisonment and 600 lashes, be tried for apostasy, which would carry the death penalty. He had been found guilty of insulting Islam through his Free Saudi Liberals website and in television comments.

As in any dictatorial, theocratic state, the authority of god is often used to justify or enforce the authority of the rulers, making the monarchy as unquestionable as religion. The situation for anyone expressing dissent in Saudi Arabia has never been good – but the new set of laws broadens and codifies this oppression. That should be a concern not just for atheists, but for anyone seeking change in Saudi Arabia.