This article is a preview from the Summer 2014 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

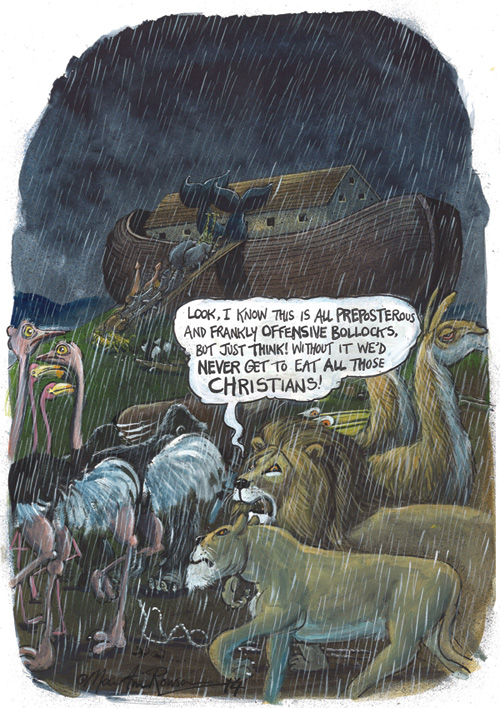

Noah, Darren Aronofsky’s star-studded film based on the biblical story of Noah’s Ark, is right at the top of my current “to-miss” list, despite the evangelical protests which usually sell a film’s merits to me. The reason for this is simple. Noah’s Ark is undoubtedly one of the most irredeemably cruel and judgemental stories I have ever had the displeasure of reading. Genesis 6:5-7 reads: “The Lord regretted that he had made human beings on the earth, and his heart was deeply troubled. So the Lord said, ‘I will wipe from the face of the earth the human race I have created – and with them the animals, the birds and the creatures that move along the ground – for I regret that I have made them.’”

A genocidal tantrum of epic proportions, designed to obliterate mankind and all living creatures, including babies, woolly mammoths and ickle bunny wabbits. Surely he could have sent a nasty plague to harm only the evil-doers, or shot a few precision-targeted bolts of lightning instead?

Of course, Noah’s Ark is far from unique in the Old Testament in its gruesome depiction of a vicious God. But Noah’s tale is special. It is the only biblical story, violent or otherwise, that has spawned Fisher Price toys and nursery decoration. It has mutated into shape-sorters, jigsaws and birthday cakes. This act of vengeful genocide has somehow morphed into the bedtime reading of toddlers. Playmobil doesn’t do crucifixions or stonings or the serving of men’s heads on platters. It doesn’t even make playsets for the happy miracles like the curing of the sick or multiplying loaves and fishes. Noah’s Ark, however, with its cute pairs of animals lined up in an orderly fashion to board the cruise of their lives, is the ultimate wolf in sheep’s clothing.

The story’s unique status as fun cuddly kid’s yarn means that it holds the dubious honour of being the Bible text most often given as a present by religious relatives to the children of atheist parents. The pious relatives will typically smile sweetly as your offspring unwrap this faith-filled Trojan horse of a picture book or wooden toy whilst holding their best “butter-wouldn’t-melt-and-I-haven’t-just-tried-to-introduce-religious-material-into-your-home” look.

It struck me recently why this story makes believers feel warm and fuzzy and leaves me cold. Fundamentally, they identify themselves with Noah in his self-righteous smug destiny, being saved by God for their purity and goodness, whereas I recognise myself among the rest of humanity in my watery grave, sitting as I do on the wrong side of divine judgement. Noah’s faith saved him, and I’m toast. This makes it all the less appropriate as a fluffy introduction for our children to the wonders of religion.

To be honest, it’s the disrespect inherent in this soft missionising that bothers me rather than the presence of religious books in my house per se. In fact, Noah’s Ark is a spectacularly rich text from which to springboard discussion about reality versus fiction with curious little people. There is endless fun to be had wondering together how Noah managed to build an ark half the length of the Titanic, a millennium before the Iron Age, without saws, hammers or nails. Then the minor detail of how he collected the estimated 1,877,920 species from around the globe, including penguins from Antarctica and kangaroos from Australia. What about the food supplies for a year of confinement, including fresh meat for the lions and bamboo for the giant panda? Where did the floods, which were higher than Everest, drain to? Kids will love looking up how much excrement a pair of elephants produces in a year. But my own favourite Noah-conundrum is the survival of parasites and bacteria which could only have made their way onto the ark inside human hosts. What a fun journey for Noah’s family, full of tapeworms and covered in lice and scabies, suffering from malaria and dysentery, sleeping sickness and toxoplasmosis.

The internet is full of creationists who have developed explanations for all of the anomalies of the Ark, involving magical solutions worthy of JK Rowling’s pen. My personal favourite is that he miniaturised all the creatures to make them fit. Many Christians, however, recognise that the tale stems from a time before geology, ecology, genetics or archaeology, when only hundreds of species were known. They read it allegorically. Thank goodness for that. So, here I am, scratching my head and trying to figure out what the metaphorical interpretation should be that would make it suitable for children’s bedroom walls. Is it that you should do what you’re told even if it makes you complicit in genocide? That it’s OK to punish innocents if you’re angry? Is it just a scary old-fashioned way of saying “be good or else”? Or a smug reminder that they, as people of faith, will be saved? Whichever way I look at it, the story becomes no more palatable. And when I look at those cute pairs of giraffes and elephants going in two by two, I only see the anguish and bitterness in their eyes as they watch their kin drowning all around them. Going, going . . . gone.