This article is a preview from the Winter 2014 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

It was a flattering invitation. Would I like to contribute to an academic panel discussion on Richard Hoggart’s Uses of Literacy? The discussion was to be held in Goldsmiths College, University of London, and would be a major part of a day devoted to the life and times of the writer and critic who had once been such a highly respected warden of the college.

“Count me in,” said my email to the organiser, Richard’s son Paul. “I interviewed your father on BBC Radio Leeds on the 25th anniversary of the publication of Uses of Literacy and still treasure the copy of the book that he signed for me. So I’d be only too pleased to join my fellow academics on the panel.”

“Fellow academics.” That phrase began to haunt me. It was a good 20 years since I’d been any sort of academic. I could still remember the smell of the lino in the corridor on the first floor of Wentworth College at the University of York and I just about recall my own office and the big desk and the wobbly bookcase and the plastic chairs arranged in a semi-circle for a student seminar. But I’d almost completely forgotten how to look and talk like an academic. When I first arrived at York University back in the late ’60s, I’d had to have special instruction in such matters.

“Where on earth are you going?” my colleague Andy said one morning as I was setting off across the campus.

“I’m off to give a first-year lecture,” I explained.

“But why are you walking like that?”

“I’m just walking.” I said.

“No, you’re not,” said Andy, “You’re striding. Academics don’t stride. They dodder. Like this.”

He executed a doddering walk.

“Why would I walk like that?” I asked.

“Because then everyone knows you’re thinking.”

I reckoned that I might be able to remember enough of my old style to be able to pass at Goldsmiths. Of course, if I was on a panel there probably wouldn’t be that much chance for a long dodder as I moved to the lectern, but I could at least drop a page from my notes on the way, create an audio howl by speaking directly into the lectern microphone, and then spend an inordinate amount of time sipping from a glass of water before opening my mouth.

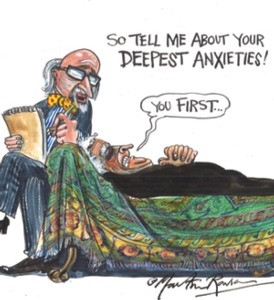

But there lay the real problem. The opening of the mouth. For although I practised and practised I simply couldn’t manage to recreate the academic tone that had, at one time, helped me secure a full professorship.

Since leaving academia I’d become dangerously inclined to present opinions as my own rather than crediting them to a pronomic other. I’d become accustomed to saying “I think” instead of “one thinks”. Neither was I able any longer to utter such words as “hegemony” and “disciplinary power” and “cultural capital” without waggling my fingers in a quote sign. And nor could I now name-drop with impunity. Whenever I so much as dared to bring Bourdieu or Habermas or Foucault into a conversation, they came out sounding more like Chelsea’s midfield than a colloquium of high-powered academic theorists.

On the day of the Hoggart seminar I employed all the resources I could muster to give the impression of being a fully paid-up don. While others were speaking, I nodded enthusiastically from time to time, wrote the occasional note with an urgency that suggested my life had just been threatened by the speaker’s conceptual apparatus, and, despite the proximity of the several hundred attendees, managed to suggest that I was otherwise wholly engaged in peering into the theoretical distance.

I began my own talk by praising everyone in sight: my fellow panellists, the conference organiser and the audience. From then on, it was all downhill. I’d forgotten that academic audiences pride themselves on restraining their enthusiasm, so much so that when my occasional jokes and telling aperçus failed to elicit any applause, I found myself becoming louder and louder. Less and less impersonal. Less and less conceptual. More and more haranguing. “You know that what I’m saying is true,” I bellowed at any remaining unbelievers as I scooped up my notes and strode back to my platform seat.

Although the stage was quickly full of audience members at the end of the session, no one approached me except for an elderly man with a prominent hearing aid who told me that he’d enjoyed my presentation so much that if ever the opportunity occurred he’d certainly vote for my party. What exactly was it called?