This article is a preview from the Autumn 2015 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

After hearing of the death of a much-loved friend, Paul B. Preciado conducts a ritual. Solo, to video camera. He opens a 50-milligram pack of testosterone gel, applies it to his left shoulder. Then he shaves his head, gluing the hair above his upper lip to form a moustache. Next, he shaves his vulva, his anus. He fastens on a strap-on dildo and harness. He penetrates his lower body with two other dildos: a “realistic” one and an “ergonomic” one. On his knees, bending over with his back to the camera, he touches his head to the floor. He speaks to the camera: “This testosterone is for you, this pleasure is for you.”

Despite his pain, Preciado, a transgender writer and curator, presents himself in total control. He moulds himself in homage to his dead friend, the Parisian writer Guillaume Dustan. This ceremony is a cry of loss, echoing Dustan’s work on HIV/AIDS and the drug-charged orgies of his set of gay male friends. Using synthetic testosterone, prostheses, a moustache, Preciado creates, for a moment, not just a changed body but an emotional rawness. By recording it on video and in his book Testo Junkie, a despair-fuelled moment of transition is captured and communicated to a wider, unseen audience.

Self-creation and re-creation have never been easier. New technologies mean that, in theory, we have more potential than ever to represent ourselves as we feel – or as we would like to be. In 2015, body modification has entered the mainstream, and transformed bodies have dominated the national news. Transgender women are at the forefront of this, reflecting public fascination with femininity. Following months of speculation, a former US Olympic athlete came out as trans, using the name Caitlyn Jenner, to great fanfare. Trans actress and activist Laverne Cox also returned to our screens in Orange is the New Black, less than a year after becoming the face of Time magazine’s “Trans tipping point”.

The medical techniques that enable people to do this are just part of a spectrum of technologies that fundamentally alter the body. One third of women in the UK are on the contraceptive pill, which first became available in 1960. The pill works by releasing synthetic hormones – oestrogen and progesterone, or just progesterone – to prevent pregnancy. Some versions also stop periods, challenging the idea that we can easily define gender along biological lines (do women who don’t menstruate while on the pill stop being women?). Other hormone-based contraceptive technologies, like the coil or the implant, can do the same.

The possibilities for body alteration today are broad: a barrage of cosmetic or reconstructive surgeries, piercings, other hormone therapies, tattoos, implants and “scarification”, when designs are made on the skin through cutting or branding.

This desire for control – not just over how our bodies are shaped, but over how we’re seen by others – is accelerated by external technologies such as the internet. Like Madonna, we are all on a constant loop of reinvention, and the difference between online and “In Real Life” is becoming ever more blurry. It is not just that if I get a new tattoo I can upload it to Instagram, filter it to alter the colours, present it in its best light. The link is stronger than this. We joke that if it isn’t on Facebook it didn’t really happen, and part of this is true: we know who people are through their online profiles. Part and parcel of any experience is the offering up of that experience to social networks for approval or reassurance. An online personal brand may be easier to project than an offline personality, but change in the former drip-feeds the latter. We become our images of ourselves.

We are physically and emotionally modified by our online engagement, just as we modify ourselves deliberately to appear online as we want to. Whether we like it or not, for most of us, our friend and family circles are networked through a digital interface.

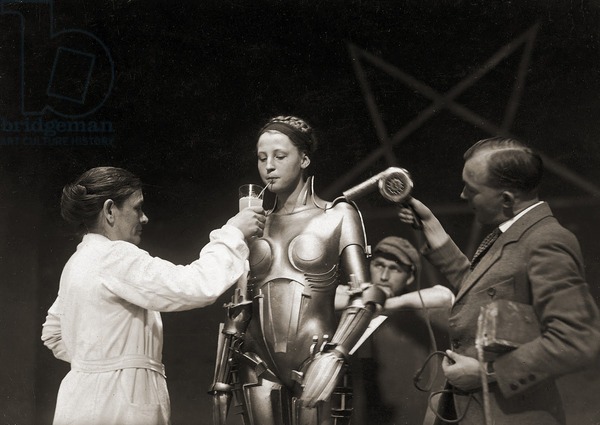

Science fiction has repeatedly played out visions of societies fully dependent on technology. As a child I was intrigued and terrified in equal measure by Star Trek’s “The Borg” – an alien collective consciousness, or hive-mind, who turn up every so often to attack the good guys on the Starship Enterprise. The Borg are literal techno-bodies, organic humanoid forms whose flesh is fused with robotic wiring, chest pads and chunky eye-pieces. Their look is all-black on pallid skin, part cybergoth, part BDSM-aesthetic. To attack, they board a space ship and “assimilate” whoever is on board, forcibly making them part of the Borg too. Their famous slogan: “Resistance is futile, you will be assimilated.”

The Borg reflect a classic cultural anxiety about machines gone wrong – escaped, rebellious machines determined to take control of humans. They get sexed up for the 1996 film First Contact, in which the robot Data is taken hostage by the Borg Queen, a latex-skinned, leather-clad femme fatale who tries to persuade him to join her by holding out the promise of greater humanity. This domination fantasy brings the techno-body full circle: the Borg Queen blows sensually across artificial human skin that has been grafted to Data’s robot arm, causing him to feel erotic sensations he’s not been able to feel before. The Borg Queen takes control of Data’s body: tech controlling tech, “human” is just a pawn in the power-play between them.

Of course, we are not (yet) the Borg, but does the appearance of increasing autonomy over our bodies mean we relate to them – and to each other – differently from in the past? If we can be someone new, and so can the others around us, then fixed identity seems anachronistic. It is no longer scientific capacity that holds us back, it is money, and the medical and legal gatekeeping that restricts access to what we desire. To exist as veiny circuit boards, silicon nerves and bloody connectivities is possible, but restricted by capital.

Yet technology has larger implications than bodily autonomy. While it is marketed to us as liberating, in a society where power is unequally distributed it can be oppressive. Autonomy, of course, is dispersed across race, class, gender, nationality, ability – cosmetic surgery for some women is lauded, while for others it brings scorn. For less well-off women it can lead to sneering tabloid headlines: “Benefits mum blasted over £20k ‘designer vagina’ surgery spree”. And while cosmetic surgeries and hormonal interventions become cheaper and more socially acceptable in general, and trans and non-binary gender identities are also proliferating, this doesn’t mean assigned categories like gender are becoming less important. The backlash against greater visibility for any minority is – as ever – violence. Worldwide, a trans person, overwhelmingly a trans woman of colour, is killed every two days. A US study found that trans people are four times more likely to be living in poverty than cisgender people – with the proportion rising for trans people of colour. The lure of choice can act as a replacement for collective organisation against the people who profit from our consumption: the governments, the gatekeepers, the corporate leaders.

Control over the self becomes a constraint, the imperative for women to be constantly on hormones, to alter their bodies to look better, to become someone new, to fit in. For trans people to pay for expensive surgeries that they can’t afford or don’t want. It’s profoundly isolating: each of us solitary, working on our personal brands. While more options might imply greater control over our surrounding worlds, choice does not translate to power.

At the same time, governments and police have ever more opportunities to surveil people remotely – Edward Snowden’s revelations last year were just one indicator of the ease with which data about us is collected. Snowden revealed that the American National Security Agency spies on US residents, accessing their phone records and online data – and that the British equivalent GCHQ is involved in sharing similar data. The UK police can currently legally access data about our phone conversations, texts and emails, including who they are sent to, where and when. They make one request for information every two minutes, according to the campaign group Big Brother Watch. And the government is now pressing through the “Snoopers Charter”, or Investigatory Powers Bill, which will force internet service providers and social media networks to keep records of their users’ activities. Information collected will include Facebook conversations, internet searches, Snapchats and Whatsapp group messages (though encrypted messaging services like Whatsapp may just be banned). Under the new law, these will be passed to the government on request.

Meanwhile, people who own the technologies that we use literally profit from selling our identities, our bodies. Facebook makes money from selling data to advertisers: browsing online shops immediately brings up what you’ve been looking at at the side of your profile. This, combined with the automated face recognition technology that allows the site to suggest photo tags, means all sorts of companies know exactly who we are, where we are and what we believe in. If you use any technology, privacy is no longer possible. It leaves us worrying about our own bodies, and our own individual happiness, with seemingly little control over the bigger picture.

Would it be different with a different model of ownership? Shulamith Firestone was one of the earliest feminists who took up the idea of controlling technology as a pathway to liberation. Her book The Dialectic of Sex, which was reissued by Verso this year, was first published in 1970 when she was 25 years old. Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto followed in the mid-’80s, inspiring Sadie Plant’s Zeros and Ones and Australian collective VNS Matrix’s “Cyberfeminist Manifesto”. At the same time, Afrofuturist feminist writers like Octavia E. Butler and Alondra Nelson were also emerging; Butler was writing science fiction from the 1970s onwards; Nelson created the afrofuturism.net listserv in 1998.

Three things are at the centre of Firestone’s vision: cybernation, the automation of women’s reproductive labour and the destruction of the nuclear family. During cybernation, machines will take over the labour currently done by people – altering our relationship to “wages and work”. Firestone believed that cybernation would lead to a scarcity of work, creating “massive unrest”. This in turn, she said, would lead to feminist revolution. Forty-five years ago, before IVF was made properly available, she argued that reproduction should be fully automated, as it is a “barbaric” form of work. Her “cybernetic socialism” would divorce reproduction completely from women’s bodies, creating one of the conditions for women’s liberation. She says:

In order to deal with the profound effects of fertility control and cybernation, [we will need] a new culture based on a radical redefinition of human relationships and leisure for the masses. To so radically redefine our relationship to production and reproduction requires the destruction at once of the class system as well as the family ... Machines thus could act as the perfect equaliser. Childbearing could be taken over by technology. Any childrearing responsibility left would be diffused to include men and other children equally with women.

Similarly, Donna Haraway considers the relation between techno-bodies – she uses the term cyborgs – and political liberation. Her argument is that as boundaries between humans, animals and machines have broken down, creating a “cyborg world”, new possibilities for political coalitions between different kinds of groups are opening up. This would mean overthrowing the “dominations” of race, of class, of gender, of sexuality. Yet her work is not about a straightforward redistribution of control in which genderless, raceless cyborgs rise up and seize the means of production for the benefit of the masses. Instead, she points at the power of affinities – of strategic alliances built around the new identities opened up by technological advances. It can be true both that cyborgs are part of a final “grid of control” descending across the planet, and that at the same time these new technologies mean we could hold together “witches, engineers, elders, perverts, Christians, mothers, and Leninists long enough to disarm the state”.

Following Haraway, Cyberfeminism emerged in 1991, suggesting that the internet could bring about a post-gender future. British cultural theorist Sadie Plant and VNS Matrix are generally credited as originating the name. The optimism suffusing the early days of the internet is obvious. In their “Cyberfeminist Manifesto” VNS Matrix write:

we are the virus of the new world disorder

rupturing the symbolic from within

saboteurs of big daddy mainframe

The manifesto’s imagery is vivid: it calls up visions of punk anarcha-feminist street gangs turned cyberfeminist hackers – hoping to use the new world of the internet to explode gender from the inside, to take on a barrage of new identities, to rupture the symbolic from within.

Today these hopes seem overblown: we’ve lived to see that the existence of the internet has not brought us freedom from disadvantage, that “big daddy mainframe” still holds the balance of power despite any democratising tendencies.

In this light, the Afrofuturist feminist tradition looks more realistic. Contrasting with the genderless utopian imagination of the cyberfeminists, Afrofuturist feminists root their approach to technology squarely within ethnicity and gender, imagining future possibilities that include bodies that are generally seen as other or alien. In her 1998 call-out for the creation of an online Afrofuturist community, Alondra Nelson wrote: “Afrofuturism simultaneously references the past and imagines the future of black life using such symbols and concepts as cyborgs, mad scientists and alien abductions.”

Have we become techno-bodies? Are the writings of these theorists anything more than wild speculation? Control of the self should not be underestimated as a form of power. Developments in artificial reproduction have allowed us to gestate babies outside wombs and enabled control over fertility. The ability to be seen as we wish to be seen saves lives. This is particularly true for trans people, but it applies to everyone on some scale. The development of birth control in the 20th century has been a major factor in the advancement of women’s rights.

Yet women’s responsibility for both child-bearing and child-rearing continues – and is further displaced on to the women of colour who provide care for the children of employed, richer white women. While automation proliferates, it has not yet led to a society-wide upheaval. State control is resilient – new forms of resistance are met squarely with reworked methods of suppression. This kind of control is wrapped up in, enhanced by, the surveillance and control of categorisation by gender and race, by class, ability and nation.

These categories keep us in our place; they train us in docility and domesticity. That’s why any futurist vision of a technological future requires more than ownership over machines; it requires full liberation, the destruction of these hierarchies. The point is that common ownership of technology does not mean much without a wider politics of liberation. Without this, technologies can only shadow forms of freedom.